A stopping point along the vast stretch of shore between the Atlantic coast city of Bluefields and the Costa Rican border, Monkey Point is the easternmost rocky outcropping of land. Offshore cays with names like Frenchman, Three Sisters, and Silk Grass hug the shoreline, which is fringed with coconut groves. Just south of the community, the coast recedes inland to create a natural harbor protected from northerly winds and high seas. Small homesteads are situated along sandy beach inlets or on high bluffs overlooking the sea. The views from the bluffs are spectacular, the ocean breezes salubrious, and the surrounding hillsides verdant. One can imagine that Monkey Point offered an appealing haven to West Indian migrants who established the community in the nineteenth century. Just a generation or two removed from slavery, these migrants came to work in the bustling enclave economy that grew with the intensification of foreign capital in the region. But rather than depending exclusively on wage labor—a master of another sort—for their livelihoods, they settled lands in peripheral regions of the coast where they could fish, farm, and enjoy a rural lifestyle free from the conditions of racial servitude that structured the postemancipation Caribbean.

The freedom their Creole descendants found in Monkey Point was an attenuated one. Periodic upheaval and rapid change interrupted long stretches of rural quiescence and relative autonomy. Nicaragua’s military annexation of the Mosquitia in 1894 followed by the construction of the Monkey Point–San Miguelito Railroad in 1904 brought foreign capital, white engineers and administrators, and black laborers to the community. When the railway project collapsed in 1909, community people went on with their lives surrounded by the detritus of a failed capitalist venture. Half a century later in 1963, they were introduced to Cold War militarism when the Somoza regime allowed an anti-Castro Cuban exile group to construct a commando training camp on their land after the failed invasion at the Bay of Pigs. The Cubans put up barbed wire around their encampment and knocked down the big Ibo trees in the back to build an airport. After the camp disbanded, the concrete landing strip grew a thick layer of grass, the commando barracks rotted away, and local families again resumed their lives amid the spent shell casings.

Monkey Point people stayed on the land, organizing community life around the subsistence economy, vernacular cultural practices, and intermittent labor migration until the outbreak of the Contra War in the early 1980s. As the conflict deepened, they joined the contras to fight the Sandinista state or fled north to Bluefields and south to Costa Rica. After the war, the Sandinistas established a new autonomy regime for the Atlantic coast, and community people began to return and mobilize for rights to territory and self-governance, drawing on their new status as multicultural citizens of the Nicaraguan nation. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, community leaders allied with their indigenous Rama neighbors and built a social movement for autonomous rights with the support of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and human rights advocates. In 2009, more than a decade of activism paid off when these communities secured title to a large swath of coastal lands, now officially recognized as the Rama-Kriol Territory.

As the process of recognition unfolded, the state remilitarized the region under the auspices of the hemispheric drug war and developed plans for an interoceanic dry canal or high-speed railway that would dispossess local people of their land. The homicide rate doubled after militarization, and the region became the most violent in the country (Policía Nacional de Nicaragua 2010). The Nicaraguan army established an outpost in Monkey Point to police the drug trade, and community people found themselves under military occupation for the third time in half a century. Already subject to color and class discrimination and living along an active coastal trafficking route, they became prime targets for counternarcotics policing and were depicted in the press and public discourse as racialized criminal threats.

Like elsewhere in Latin America, drug war militarization did not promote security. Mestizo soldiers stationed in the community used excessive force on local men and sexually harassed and assaulted local women and girls. Meanwhile, communal land tenure grew increasingly insecure as mestizo colonists settled the territory and the state moved forward with plans for an interoceanic canal. Local people understood these processes to be interconnected: Drug war militarization secured capitalist intensification, while occupying forces permitted mestizos to colonize the territory. When community people rallied to confront this state of siege, women and men mobilized in distinct ways but both embraced a politics of black autonomy.

Black Autonomy tells the story of this gendered activism and its social and experiential roots by following a community-based movement for autonomous rights from its inception in the late 1990s to its realization as a self-governing territory in 2009 and beyond. Broadly speaking, this book examines what happens to multicultural activism under conditions of prolonged violence. Postconflict Central American nations are some of the most violent democracies on Earth with homicide rates that top the global charts (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2013). Nicaragua has largely escaped this regional trend. The country has one of the lowest levels of violence and the most expansive multicultural rights regime in Central America. Yet these positive indicators belie the violence of everyday life for working-class Creoles and the failure of multicultural reforms to ensure the most basic forms of livelihood and security.

These conditions have led community activists to adopt a position of black autonomy based on race pride, territoriality, self-determination, and self-defense. For women and men grappling with systemic racism and postwar violence, black autonomy has its own gendered meanings as a way of crafting selfhood and solidarity. I theorize black autonomy as an expression of African diasporic identification and gendered political consciousness that cuts across the domains of sociality, livelihood, security, territory, and sexuality. The pages that follow describe the gendered strategies that women and men use to assert autonomy over their bodies, labor, and spaces and the forms of violent entrapment that they encounter along the way. Departing from traditional feminist ethnography, this book documents how racism and patriarchy interpenetrate the lives of both women and men and shape state-led processes such as multicultural governance, capitalist intensification, militarization, and policing. By interlacing analysis of gendered practices like storytelling, musical production, homosociality, and mutual aid with accounts of everyday and organized acts of political resistance, I show how black vernacular culture becomes a site for the production of oppositional consciousness and the basis for autonomous rights activism.

The argument I present is threefold. The first part of my argument concerns the social and experiential organization of politics. My ethnography reveals a porous boundary between everyday and organized politics, demonstrating how vernacular practices and subjective experiences drive collective challenges to the state and capital. For instance, sociality and shared labor are not simply survival strategies or sources of intimacy and pleasure; they promote political solidarity and activism among women. Everyday expressions of patriarchal privilege and masculine authority similarly shape men’s mobilization for autonomous rights. Conversely, state and capitalist power are lived phenomena with subjective and relational effects. The coercive state is experienced in the dampness and despair of an overcrowded jail cell. Capitalist intensification is felt in the reorganization of intimate attachments between husband and wife or neighborhood friends. And patriarchal state power produces fear and familial strife, limiting women’s and men’s ability to institutionally confront sexual violence.

Second, when we take the social expression of power and the social origins of oppositional politics as starting points for understanding political action, we must centrally grapple with embodied social difference. Racism and patriarchy have deadly consequences for community people, yet women and men have distinct experiences of racial violence that are conditioned by their sexually differentiated bodies and gendered subject positions (Aretxaga 2001; Goett 2015). They also respond to violence and subordination in different ways, drawing on gendered practices to fashion complex racial selves and assert autonomy over their lives and social domains. Feminist anthropologists have cautioned that subaltern agency is not always liberatory and that resistance does not necessarily signal the ineffectiveness of power (Abu-Lughod 1990; Mahmood 2001). Similarly, I find that women and men are caught up in extraordinarily complex interpersonal and political dynamics that are textured by multiple forms of racial and gendered violence. Individual efforts to negotiate these dynamics vary widely and are not always emancipatory in nature.

Lastly, I argue that feminist activist ethnography attuned to socially differentiated politics can (in the best of circumstances) support political praxis in coalitional rights movements. Violence continues to plague Afrodescendant communities in Latin America even after they have gained multicultural recognition (Cárdenas 2012; Goett 2011, 2015; Loperena 2012). This case makes it clear that although rights to land and natural resources are a crucial step in the struggle for justice and equality, they do not resolve complex patterns of state, structural, and interpersonal violence. Situated experiences of violence and state power matter intensely to struggles for social justice today, but subaltern politics often remain fragmented in postwar Central America. Tracking the conditions that support and undermine collective resistance in the face of prolonged everyday violence provides critical political knowledge that can help build a more expansive politics of liberation.

Scholarship on ethnic autonomy in Latin America has focused on the political evolution and institutional design of autonomous regimes that devolve state power and accord special cultural and political rights to indigenous and Afrodescendant communities (see Van Cott 2001). Nicaragua represents one of the earliest and most expansive cases with the development of regional autonomy for the Atlantic coast during the Sandinista Revolution in the 1980s (Díaz Polanco and López y Rivas 1986; González 1997). Later scholarship has emphasized the limits of formal multicultural recognition, whether it be the compromised conditions of autonomous politics (Hale 2011), the failure to effect structural change (Hale 2002; Postero 2007), or the particular challenges that Afrodescendants face in rights regimes based on normative constructions of indigeneity (Anderson 2009; Hooker 2005b).

A few questions emerge from this body of work. Given the widely recognized shortcomings of territorial recognition in the neoliberal context, why does it continue to matter so much to movements for autonomy (Richards and Gardner 2013)? How can indigenous and Afrodescendant peoples move beyond the more limiting aspects of recognition to realize deeper aspirations for autonomy, breaking bonds of dependency on the state and capital altogether (Hale 2011)? And finally, to what degree is this kind of radical autonomy really possible, given how neoliberal states and economies depend on autonomous and flexible organization and participation (Böhm, Dinerstein, and Spicer 2010)?

This book grows out of these debates, even as it moves beyond to focus on the shared values and practices of daily life that support autonomous social and political forms. I am particularly concerned with how these values and practices persist over time despite the violent and disabling forces that besiege communities like Monkey Point in postwar Nicaragua. I start from the premise that autonomy, as a real and vital social practice, is far more expansive and robust than highly compromised multicultural autonomy regimes might indicate. Indeed, much of the radical potential behind autonomous politics stems from intimate spheres of social life, which remain peripheral in most studies of social movements. These values and practices drive oppositional politics in Monkey Point, taking shape in community-based mobilization against the state and capitalist interests. The obstacles to a more expansive politics of liberation are similarly evidenced by the violence of everyday life, which can at times hinder solidarities within the community and beyond.

Neoliberal Rights Activism

For the last three decades, the political fortunes of Nicaragua have tacked back and forth between the right and left with U.S. intervention often playing a decisive role. The country has transitioned from forty-two years of Somoza family dictatorship (1937–1979) to a leftist popular revolution led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) (1979–1990) to neoliberal democracy (1990–2007) to the return of the postrevolutionary Sandinista Party to power (2007–). After the Sandinista Revolution upended Somoza family rule in 1979, an illegal U.S. campaign of destabilization and a costly war with CIA-backed contra insurgents threw the country back into political turmoil. War weary and suffering from deep economic crisis, the Nicaraguan electorate brought a center-right coalition to power in 1990, beginning the country’s transition from revolutionary socialism to neoliberal democracy.

I first traveled to Nicaragua in 1998 just eight years after the Sandinista electoral defeat. These years of center-right rule had chipped away at the socialist legacy with a “slow motion counterrevolution” that sought to “tie internal social order to transnational order” through neoliberal governance and economic policy (Robinson 2003: 75). Under the stewardship of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the postrevolutionary state dutifully enacted neoliberal reforms (Spalding 2011: 219). Multilateral development banks had unprecedented influence over national policy making, and NGOs replaced popular revolutionary organizations as the primary vehicles for political participation.

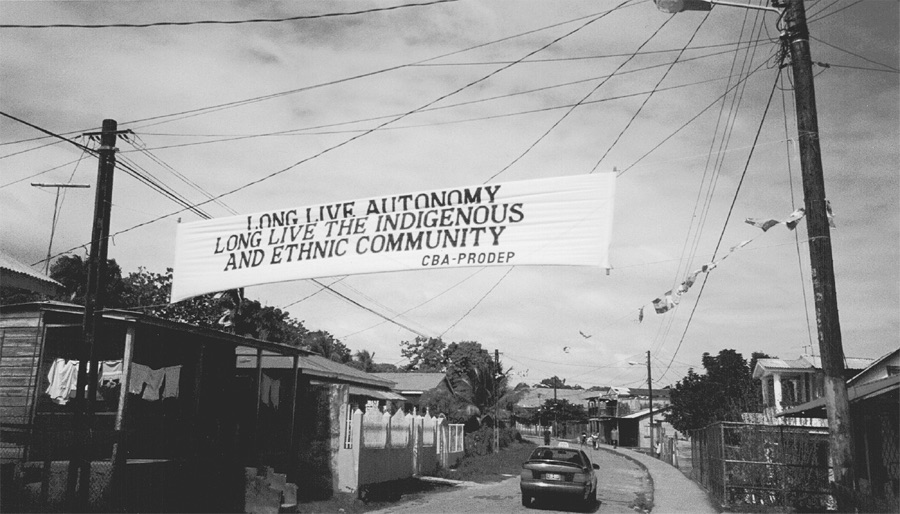

When I lived and worked on the Atlantic coast between 2001 and 2004, the World Bank promoted expansive multicultural reforms, and international NGOs and European development agencies bankrolled civil society activism for multicultural rights (see Figure I.1). Weeks after my arrival in August 2001, the indigenous Mayangna community of Awas Tingni won a precedent-setting case against the Republic of Nicaragua in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The Court ruled that the state had violated the community’s right to property and mandated the demarcation and titling of their lands along with the claims of other Atlantic coast indigenous communities (Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos 2001). Afrodescendants were not included in the ruling, but the Court’s decision applied to Creole and Garifuna communities, as they enjoy full multicultural rights to land and natural resources under Nicaraguan law.1

Just months after the decision, Enrique Bolaños won the presidency on an electoral platform that emphasized democratic reform and rule of law. In contrast to his notoriously corrupt predecessor Arnoldo Alemán, Bolaños made compliance with international law a new priority and sought to reconcile state policy on multicultural rights with reforms outlined by the Inter-American Court and World Bank. Less than a year into his presidency, the National Assembly approved Law 445, which provides the legal framework for the demarcation and titling of indigenous and Afrodescendant territories.2 The law reflects years of negotiations between the Nicaraguan state and Atlantic coast communities that were largely funded by the World Bank. The final version of the law is expansive, granting indigenous and Afrodescendant communities the right to possess and govern communal lands under the authority of democratically elected territorial governments (Goett 2011: 364–365).

Organized civil society was a vibrant political space during these years, and I worked with communities, local and international NGOs, and regional universities to advance territorial demarcation and autonomous rights. I traveled up north to help carry out the participatory mapping of Awas Tingni’s territory in 2002 and 2003. In the south, I collaborated with regional universities to develop the organizational capacities of indigenous and Afrodescendant communities in the Pearl Lagoon basin and the Rama-Kriol Territory. Most of my work was in Bluefields, where I joined lawyers from the Center for Legal Assistance to Indigenous Peoples (CALPI, Centro de Asistencia Legal a Pueblos Indígenas) and International Human Rights Law Group to provide support to Rama and Creole communities as they mobilized for territorial rights. I went to countless meetings and workshops on multicultural rights and did the mundane work of political organizing with community leaders and their NGO allies.

This was a period of intense mobilization that transformed ethnic politics on the coast as indigenous and Afrodescendant territorial governments became established institutional entities and international advocates lent increased legitimacy to multicultural rights. In a moment of pessimism years later, I asked an activist named Harley Clair from Monkey Point if Law 445 really changed anything for community people. This was in 2011—almost a decade after the law went into effect. The community had received its territorial title but was under military occupation and experiencing ongoing land incursions by mestizo settlers, and leaders were attempting to hold the Nicaraguan military accountable for the sexual abuse of local girls. The force of his response surprised me. “Yes girl,” he insisted, “it have impact. Maybe the impact mightn’t be big. But then you have more international coming to look on the community more serious, the territorial government more serious. And then the same government people them, them fighting hard for not to respect it, but openly they have to respect.” From his point of view, multicultural reforms and civil society organizing had resulted in new political legitimacy and power vis-à-vis the mestizo state.

Still, my memories of these years are tinged with ambivalence. As I immersed myself in the daily work of multicultural rights activism, I found that institutional rationales often overshadowed community perspectives and needs, limiting the degree to which deeper forms of autonomous social action might take root in neoliberal civil society. A good deal (but not all) of this work was dominated by discrete project-driven agendas, obligations to international funders, bureaucratic procedures, the veneration of professional expertise, and the neoliberal ethics of citizen participation, rather than real citizen power. The most effective NGO advocates like CALPI and IBIS (a Danish organization for development cooperation) provided tangible services in the form of legal representation or logistical and technical assistance with the territorial demarcation request the community submitted to the government. But long-term support of this kind was the exception rather than the rule. Monkey Point activists often reminded me that NGO allies come and go, and it is best not to depend too deeply on their support. Even more telling was an intractable reality: Civil society organizing, statutory reform, multicultural recognition, and territorial demarcation did not seem to curb the violence of everyday life or the daily burden of structural inequality for most community people (also see Hale 2002, 2005; Postero 2007).

Outside of the institutional environment, I spent my time traveling to Monkey Point and socializing with the many families who maintain primary residences in Bluefields. As I developed relationships with community people, I became aware of the inner realms of sociality and conviviality that shape autonomous aspirations and activism. In these spaces of everyday intimacy, black cultural practices and vernacular ways of being in the world are powerful sources of oppositional agency. By the vernacular, I mean everyday ways of doing things, things that work well and make sense in their own context, cultural practices that encode valuable local knowledge about relationships, subsistence, and right ways of living that are not dictated by institutional, capitalist, or state-centric prescripts (Scott 2012). Ivan Illich used the term vernacular to denote “autonomous, non-market related actions through which people satisfy everyday needs—the actions that by their own true nature escape bureaucratic control, satisfying needs to which, in the very process, they give specific shape” (1981: 57–58). The vernacular includes “modes of being, doing, and making” like everyday subsistence practices, household activities, patterns of reciprocity, food preparation, linguistic conventions, sociality, pleasure, and play (Ibid.: 58–59). Hardt refers to these activities as “biopower from below” that produces intimate relationships, collective subjectivity, and community (1999: 89).

A focus on biopower from below might seem to eschew transnational modes of identification, but vernacular cultural practice grounds community people’s everyday sense of themselves as black, diasporic, and autochthonous. Focusing on the African diaspora in Central America, Edmund Gordon and Mark Anderson argue for more ethnographic attention to actual processes of diasporic identification within communities, underscoring the importance of racial formation and cultural practice “in the making and remaking of diaspora” (1999: 284). Monkey Point people actively identify with distinctively black diasporic historical experiences. Social memories of slavery and racial servitude shape the stories they tell about migration from the Caribbean and resettlement in Central America. They brought with them vernacular cultural practices such as culinary and linguistic traditions, spiritual orientations, medicinal knowledge, and farming customs, which they then adapted to the local environment and economy. They formed close ties with indigenous people in the region as they underwent a process of becoming both Creole and autochthonous Mosquitians in the nineteenth century.

Community people continue to identify with other black people in the Caribbean today, consume West Indian soca, reggae, and dancehall, and embrace black diasporic modes of dress and stylistic self-presentation. They draw political inspiration from diasporic figures such as Malcolm X and Bob Marley. Moreover, they understand their own experiences of violence and political struggle to be connected to wider demands for racial justice in the African diaspora. Monkey Point people take pleasure and pride in black diasporic identity and vernacular cultural practice, the reproduction of which manifests as a self-conscious practice of freedom in the face of racism, structural inequality, and annihilating violence. Although tangential to NGO advocacy, these practices and related values are animating forces in community activism.

Over time, I also became acutely aware of how systemic inequality and violence curtail opportunity and cut short lives. By the end of the 1980s, the Nicaraguan economy was in shambles. The final years of the Sandinista Revolution were marred by armed conflict, a U.S. trade embargo, diminished social spending, massive external debt, hyperinflation, unemployment, and a hurricane that destroyed 80 percent of the structures in Bluefields (Arana 1997: 82–83; Stahler-Sholk 1990). After the transition to neoliberal democracy, the country’s economic outlook remained grim. IMF-mandated austerity, privatization of state-run enterprises, and trade liberalization in the 1990s resulted in further cuts to social spending, rising unemployment, and the loss of national markets for rural producers. Poor Nicaraguans bore the brunt of neoliberal economic policies, which resulted in class restructuring and immiseration (Robinson 1997: 35–36). Despite steady economic growth after the initial years of structural adjustment, market-oriented reforms failed to resolve entrenched inequality, and poverty rates remained stagnant in the 1990s and 2000s (Spalding 2011: 220–221).

For Monkey Point people, armed conflict and postwar drug violence compounded these economic processes, accelerating land loss and cash dependency as families left their farms and joined a superexploited surplus labor force in Bluefields. From the 1990s onward, out-migration to work in the global service sector became one of the few viable earning strategies for cash-poor families struggling to get by in Bluefields. Prolonged violence, displacement, land loss, natural disaster, unemployment, scarcity, and institutional racism and sexism place a taxing emotional and physical burden on families, providing the material basis for substance abuse, ill health and early death, interpersonal and drug-related violence, and frequent conflicts with the police, military, and mestizo justice system (Farmer 2004). These diverse expressions of violence form webs of association and collusion, resulting in a “continuum of violence” with systemic roots and effects that exact a toll on community life (Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois 2004). In the absence of security, employment, and social services, local people grappled with postwar violence the best ways they knew how, relying on expansive social networks for support and turning to autonomous activism as an outlet for redress.

1. The Atlantic coast is home to seven formally recognized ethnic groups, including: indigenous Miskitu, Mayangna (Panamahka and Tuahka), Rama, and Ulwa; Afrodescendant Creole and Garifuna; and Indo-Hispanic mestizo. After decades of land colonization, mestizos who are originally from other parts of the country are now the demographic majority in the region (Instituto de Estadísticas y Censos 2005).

2. Ley del Régimen de Propiedad Comunal de los Pueblos Indígenas y Comunidades Étnicas de las Regiones Autónomas de la Costa Atlántica de Nicaragua y de los Ríos Bocay, Coco, Indio y Maíz.