We are at the dawn of a new era—the Impact Era—in which nonprofits will play an ever more vital role in supporting, safeguarding, and sustaining American civil society. All of us—nonprofit executives, philanthropists, grant makers, board members, and everyday donors and citizens—must answer a question that is fundamental to our collective future: do we want a robust, high-performing nonprofit sector, or don’t we? If the answer is yes, then we must move forward boldly. We must adopt the kind of transformational leadership that typifies our most ambitious philanthropists and social entrepreneurs. We must direct an ever-greater share of our national wealth transfer toward nonprofits that will bring a rigorous focus on impact to the use of these resources.

Much is at stake as we enter the Impact Era. Indeed, given the centrality of the nonprofit sector to American life, the stakes of this shift could not be higher. In the United States, nonprofit and other civil society organizations fulfill needs that in most other countries are met by government or families—or not at all. Nonprofits, for instance, provide approximately 70 percent of all inpatient community-hospital care, and they serve about 30 percent of all students enrolled in four-year collegiate institutions or in postbaccalaureate programs.1 (Most US postsecondary students, of course, attend public institutions of one kind or another.) In addition, nonprofits account for a large portion of the cultural programming provided by museums, theaters, and various performing arts groups. Moreover, even as US politics become ever more strident and divisive, Americans still come together to donate their money and time to charitable organizations that provide a range of essential human services, including foster care for children in need; support for the hungry, the homeless, and the disabled; nursing-home services for the elderly; and more.2

Americans even allow (with only modest public debate) tax deductions for personal contributions to any of the more than one million nonprofits designated by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as 501(c)(3) organizations. They support independent schools, universities, and arts organizations through both ongoing donations and endowment contributions. They work through charities to act on their deeply held values, and they give tithes and time to religious organizations ranging from the traditional—Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Buddhist—to the harder to categorize. Whatever their many differences, Americans still find common ground in their support of a highly diverse nonprofit sector.

The French political commentator Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed that “Americans of all ages, all stations in life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations. There are not only commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but others of a thousand different types—religious, moral, serious, futile, very general and very limited, immensely large and very minute.”3 Tocqueville made his observation in the 1830s during his epic, seven-thousand-mile journey across the young United States and recorded it in his classic work Democracy in America. “At the head of any new undertaking, where in France you would find the government or in England some territorial magnate, in the United States you are sure to find an association,” he wrote.4 Although nearly two centuries have passed, and our nation has changed immeasurably, his description of American civil society continues to ring remarkably true.

The United States has the world’s largest nonprofit sector, with more than $1.7 trillion in total revenue—a figure that is equivalent to approximately 10 percent of US gross domestic product (GDP).5 Further, US charities are more dependent on philanthropy than are similar organizations in other developed economies: from 1995 to 2000, philanthropy accounted for 13 percent of revenue for charitable organizations in the United States, compared with 9 percent in the United Kingdom, 3 percent in Germany, and 3 percent in Japan.6 Often forgotten is that the US nonprofit sector is a major instrument of government for the delivery of social and other services. Many nonprofits, in fact, provide their services as contractors of government and require government grants and fees to survive; the relationship is frequently one of mutual dependency and benefit.

In truth, for all its importance, the charitable sector might best be characterized as the impoverished stepchild of business and government. It remains chronically underfunded, relies extensively and consistently on voluntary gifts of time and money—inconstant though such gifts often are—and delivers services that benefit society overall but whose natural supporters are disparate and unorganized.

Equally troubling, one of the foundational elements of American civil society—the willingness to form and maintain an association to tackle a shared interest or goal—may be at risk. This trend was articulated by Robert D. Putnam in his 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.7 Putnam argued that Americans took part less often in social activities and volunteer work, voted less frequently, and were less likely to join labor unions, churches, parent-teacher associations, and fraternal, civic, women’s organizations—and even bowling leagues!—than in the past. With fewer social ties and associations, Putnam suggested, many positive aspects of American life may be lost; even the performance of representative government, which is highly dependent on the norms and networks of civic engagement, could be affected. Eleanor Brown and James M. Ferris used data collected by Putnam and found that people who are engaged with congregations, alma maters, clubs, or other groups do, in fact, give more than those who are not.8

At the same time, Americans are on the cusp of the greatest transfer of wealth in history, with baby boomers—who are beginning to ponder the great white light in the lessening distance—taking the lead in that process. Between 2007 and 2061, according to one scenario in a recent study, the baseline amount of charitable giving for US households will come to about $19 trillion. Yet beyond that amount, according to the study, $59 trillion will transfer from households to a variety of entities either when wealth holders pass away or while they are still living. Slightly less than $7 trillion of that total will go toward estate taxes and estate fees. But charitable gifts, bequests to heirs (who in turn will direct some portion of those bequests to charitable causes), and other transfers during wealth holders’ lifetime will account for the remainder.9 The scale, timing, and focus of the portion that goes to philanthropy are still very unclear and subject to influence—which is one of our reasons for writing this book, and for writing it now.

Never in American history have the challenges posed to civil society been more striking. Never before has the potential of civil society organizations to create impact been greater. That twofold reality helps to define the contours of the Impact Era. It is our aim in this book to offer a plan of action that will help ensure that the nonprofit sector—the most American aspect of American civil society—will earn the right to expand its role and maximize its impact during this new era. Citizens working together in common purpose to provide for their community is one of the most essential elements for continuing a vibrant, diverse democracy, even more so as it seems to grow more divisive.

An Exceptional History

Much of what we still view as the essential infrastructure of the nonprofit sector arose from uniquely American responses to the conditions of other eras, beginning when the titans of the Industrial Revolution turned their focus to society’s broader needs.

The Industrialist Era (1880s to 1930s): The Sector Emerges

Civil society and the nonprofit sector in the United States have deep and long roots. Going back to the early nineteenth century, voluntary associations formed to oppose slavery and support abolition.10 The esteemed statesman and escaped slave Frederick Douglass was a key leader of one such group. Later, women’s associations formed to support suffrage, culture, and educational activity. The pioneering equal rights crusaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded one such association.

The US nonprofit sector as we know it today began to emerge in law and structure in the waning years of the Industrial Revolution. The first national law mentioning specific financial benefits for associations undertaking the work of social improvement was the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, which includes the earliest tax exemption in US statutes. However, this legislation was preceded by state laws, and a legal framework for tax-exempt organizations was in place in many states by the mid-nineteenth century.11

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the major wealth holders were Gilded Age industrialists like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, each of whom accumulated private wealth on a scale theretofore unknown outside royalty. Carnegie created the first of three foundations in 1905, and Rockefeller followed with his own foundation in 1913. Carnegie’s writings, including his book The Gospel of Wealth, also provided some of the philosophical and pragmatic rationale for philanthropy and for the creation of a robust civil society.12

Privately endowed foundations were also created by other important, if less well-known, philanthropists. Margaret Olivia Sage inherited a fortune from her husband, the financier Russell Sage, in 1906. She immediately began giving it away and established the Russell Sage Foundation, dedicated to “the improvement of the social and living conditions in the United States.”13 Julius Rosenwald, who owned part of Sears, Roebuck & Company, celebrated his fiftieth birthday by giving away $700,000 and encouraging others to “give while you live.”14 He befriended the famed black educator Booker T. Washington, whom he credited for helping “his own race to attain the high art of self-help and self-dependence” and “the white race to learn that opportunity and obligation go hand in hand, and that there is no enduring superiority save that which comes as the result of serving.”15 Rosenwald founded a foundation (the Rosenwald Fund) that was designed to spend down all its money within twenty-five years of his death, and he was thus the first American philanthropist of note to require that his wealth be used for current needs, not banked for perpetuity.16

Also during this period, charitable organizations began to receive special treatment for their fund-raising efforts. The Revenue Act of 1913 established an income tax and exempted certain types of income earned by charitable organizations. Legislation since then has added tax deductions for gifts to charity by individuals (1917) and corporations (1936). The current structure of Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code dates to the Revenue Act of 1954. The IRS has responsibility for the review and approval of new applicant organizations, the compilation of data, and regular reporting (since 1985) for exempt organizations.17

Through two world wars, the Depression, and the growth of the US role in international affairs, donors of all kinds emerged—from young children collecting pennies for UNICEF to major grant makers such as the Ford Foundation. Charitable giving represented approximately 2 percent of US GDP,18 funding activities from the congressionally chartered American Red Cross to grassroots groups like parent-teacher associations. National entities such as United Way (founded in 1887) and the March of Dimes (founded in 1938) formed affiliates or chapters and so built both national and local initiatives for fund raising and for supporting the needs of people in communities.19

The Independence Era (1960s to 1980s): The Sector is Defined

The 1960s and 1970s were a tumultuous period in American history, one that saw an overall decline in confidence in most institutions; this trend was so pronounced that social scientists gave it a name—the “confidence gap.”20 Charitable giving fell in parallel with confidence, declining to less than 2 percent of GDP,21 and vociferous debates over tax laws included proposals to eliminate the charitable deduction. Private foundations also faced criticisms about their grant making and governance.22

In response to the growing criticism of private philanthropy, John D. Rockefeller III recommended the creation of a blue-ribbon panel to investigate and elucidate the role of private giving. With funding from Rockefeller and others, the Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs was formed in 1973. It included foundation executives, scholars, and leaders from influential nonprofit organizations such as United Way of America, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Boy Scouts of America and was headed by Aetna Life & Casualty chairman John H. Filer.23 The Filer Commission, as it became known, compiled findings from more than eighty research projects and issued a report that defined the voluntary (aka philanthropic or charitable) sector as a “third” sector of American society, one distinct from both government and business—an independent sector. It defended the tax deduction for charitable contributions and noted that private support was “a fundamental underpinning for hundreds of thousands of institutions and organizations.”24 Such support, said the report, “is the ingredient that keeps private nonprofit organizations alive and private, keeps them from withering away or becoming mere adjuncts of government.”25 Importantly, the Filer Commission’s report also helped stave off political intrusion into private philanthropy.

However, critics of the Filer Commission, which included some representatives of charitable organizations, argued that the commission had focused too narrowly on tax policy and the role of government in funding charitable organizations. They sought to explore larger issues that encompassed the desired societal impact of philanthropic investments. From these concerns arose the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (which Rockefeller also funded in its earliest stages).26 Another outgrowth of the Filer Commission and its report was the 1980 founding of Independent Sector, which resulted from a merger of the Coalition of National Voluntary Organizations and the National Council on Philanthropy.27 One of the new organization’s first acts was to widen the tent of the sector by including religious organizations. Because the majority of Americans then participated in religious activities on a weekly basis, this move served to immediately enlarge the independent sector in terms of organizations, finances, and participants. Over time, many of these congregants began to look for accountability from their churches in regard to offerings, expenditures, and even outcomes that were consistent with what they sought in other charities.28

Sociologists and other scholars had begun to research various aspects of volunteering and giving even before the Filer Commission; in 1971 the Association of Voluntary Action Scholars was formed to share its members’ findings. (It later became the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, or ARNOVA.) Universities also established academic programs dedicated to the study of the independent sector. Universities first added managerial training and more recently added social science research to test nonprofit work for its level of impact. In the 1970s, major American universities such as Stanford and Yale initiated research and teaching programs focused wholly or in part on nonprofits and foundations; Case Western, Duke, Harvard, Indiana, and others followed later. Today, there are more than three hundred universities with organized programs that study nonprofits and foundations.

The Information Era (1990s TO 2010s): The Sector Embraces Fact-Based Decision Making

The IRS began collecting data about nonprofits on the IRS Form 990—“Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax”—for the 1941 tax year. The two-page form included three yes-or-no questions, a request for an income statement and balance sheet, and, in some cases, attached schedules.29 The Tax Reform Act of 1969 required all types of charities except congregations and other qualified religious groups to submit the Form 990.30 However, although the data were collected, once the paper forms were returned to the IRS, they received little or no scrutiny and were simply stored away. To conduct a financial analysis of a single nonprofit, much less to compare several nonprofits, was thus an extremely challenging endeavor that was rarely undertaken, except at the wealthiest foundations. This situation remained more or less the same for decades. Indeed, even as the Internet revolution was under way in the 1990s, many nonprofits continued to generate paper-based information that they stashed away in internal filing systems.31 Only a few foundations had the financial means and the staff to collect and analyze the data on nonprofit performance. The typical donor or analyst had little objective data to use in making judgments about which nonprofits were more effective or efficient.

But then, as the Internet took hold, it transformed data storage, information sharing, and communications. It also transformed people’s expectations, and the situation began to change rapidly. By 2000, it was possible to affordably share massive amounts of nonprofit data that could then be analyzed. And, like the Industrial Revolution a century before, this new era bred a generation of business leaders who sought more than financial success. Like their predecessors—Ford with the assembly line or Carnegie with vertical integration32—entrepreneurs who had made their fortunes in technology eagerly applied new methods to a variety of endeavors. The tech entrepreneurs, spawned in the world of start-ups and venture capital, brought a mind-set of “we are new, different; about the future, not the past” that in many ways is still with us today.

One of the seminal leaders of the Information Era was Arthur “Buzz” Schmidt, the founder of GuideStar, which today is the preeminent source of data on nonprofits (with eight million unique users in 2016).33 Back in the early 1990s, Schmidt, then an executive at the development organization TechnoServe, observed that the nonprofit sector lacked even the most basic data to support informed and intelligent decision making. “There was no information base to help [nonprofits] become more sophisticated, more dedicated, or more accountable in what they do,” Schmidt explained.34 To begin remedying this, he determined to digitize the Form 990, which by then had become considerably longer and included valuable information. By 1999, GuideStar facilitated public access to PDF copies of the IRS Form 990 for more than two hundred thousand charities.35 While its work has expanded since then, the organization remains focused on facilitating access to critical information about nonprofit organizations. As of 2016, GuideStar’s mission is “to revolutionize philanthropy by providing information that advances transparency, enables users to make better decisions, and encourages charitable giving,”36 and its strategic plan for 2014–2016 rests on the three pillars of data innovation, data collection, and data distribution.37

In addition to GuideStar, the Information Era saw the birth of Network for Good, which enabled users to make online donations to any nonprofit, and VolunteerMatch, which made finding volunteers and volunteer opportunities easier. Later came Charity Navigator, which grew into a popular and widely used guide for assessing nonprofits—although its overreliance on ratios and efficiency remains controversial. Still, beyond this small set of organizations, the Information Era produced few other efforts of any scale or impact.

Metaphors and practices from the start-up and venture capital community began to enter the nonprofit sector, with calls for active engagement, innovation, transparency, and accountability. The idea of venture philanthropy took hold following the 1997 publication of “Virtuous Capital: What Foundations Can Learn from Venture Capitalists” in Harvard Business Review.38 Advocates for venture philanthropy—like Mario Morino, a tech entrepreneur and a cofounder of Venture Philanthropy Partners—wanted to see the nonprofit sector adapt strategic management practices used by business in order to achieve a higher rate of social return on their investments.

There were many other attempts to leverage the Internet to propel the nonprofit sector to new heights. But none made much headway. Charitableway.com, for example, a for-profit, start-up version of the nonprofit Network for Good, burned through many millions of dollars in venture capital before spectacularly flaming out. And while it spawned several imitators that shared its aim of doing well by doing good (i.e., making a profit from online donations), almost all are now long lost to history.

Ultimately, the Information Era had less impact on the decision making and other behaviors of stakeholders in the nonprofit sector than some of us had hoped and expected. Venture philanthropy, for example, turned out to be a powerful metaphor, but it has had limited application because of the lack of a robust social capital market that could provide continuing funding for high-impact organizations and drain lesser ones. In the Silicon Valley model, start-ups are spurred by new technologies and experience hypergrowth through the creative destruction of slow-to-adapt, mature, and more costly existing businesses. But the nonprofit sector still lacks the measurement, transparency, incentives, and capital sources to support such creative destruction. Small, low-impact organizations linger; traditional nonprofits that deliver essential services struggle annually to gain funding. And some days it seems that any young, attractive social entrepreneur with an apparently fresh, if untested, idea for a social venture finds favor. Venture philanthropy remains active today, embodied in close to forty organizations around the world that carry some form of the label “social venture partners,” and the movement continues to serve its original and most impactful purpose: to attract young business leaders to philanthropy.

Much of venture philanthropy’s momentum is being subsumed today by the impact investing movement, which extends the possibility of social impact to private investment. On its face, leveraging private capital for social impact is a fabulous idea—or, more precisely, a fabulous set of ideas. But even more so than venture philanthropy, the impact investing movement has filled its very big tent with sources of capital, hopeful recipients, and pundits who have varying, sometimes different, and even competing mind-sets. While we applaud the efforts by respected thinkers like Antony Bugg-Levine, Paul Brest, Sir Ronald Cohen, Pierre Omidyar, and Matt Bannick to offer a much more focused definition of “impact investing,” we see little impetus for the movement to yield to a single definition. And now that private banks and other investment firms have grabbed hold of impact investing, we can confidently predict that the scale of investment in this category will grow. Controversially, we are very uncertain about the incremental social impact of such investment.

Indeed, perhaps the most lasting impact of the Information Era has been in the increased engagement that many people, particularly philanthropists, are bringing to the social sector. While venture philanthropy in retrospect was more a metaphor than a movement, it did provide a new generation of business leaders with a way to engage in civil society that seemed new and distinctive, and that they felt belonged to them. In many ways, this reconnection of business leaders and civil society dates to 1980, when Bill Drayton launched Ashoka, and with it the pervasive global movement known as “social entrepreneurship”—the first major effort to apply the principles of entrepreneurship to social change.

We have learned many essential lessons from the Information Era, above all that starting, leading, evaluating, and changing nonprofit organizations can be very hard and will not yield to the first instincts of the well-intentioned, however talented or energetic they may be.

The Impact Era (2000s to the Present): The Sector Reckons with New Challenges

In the current era, leaders in the social sector have an opportunity—indeed, an imperative—to build on their predecessors’ work to achieve ever-greater impact. However, to ensure that the Impact Era will succeed where the Information Era fell short, they must step back, assess the lessons they have learned, and apply those lessons in a pragmatic, persistent, and patient way.

First, although information is now plentiful, donors still lack access to useful impact evaluation data. Nonprofits still rarely use rigorous, fact-based evaluation as the basis for decision making, and they share evaluation data even less often. Donors then default to a friendly recommendation, their own intuition, or deceptive measures of efficiency. Charity Navigator is almost certainly the most popular online source of nonprofit evaluation, but its ratings are largely driven by expense ratios (yes, still)—even though sloppiness or inattentiveness to costs is only a relatively small limitation to impact in the sector. Of course costs count, but credible measures of impact are what matter first and foremost.

Second, donors still give mostly in emotional response to a fund-raising request. Strategic philanthropy, based on in-depth impact evaluations, affects only a few discussions rather than most decisions. And those nonprofits that have development or fund-raising departments focused on large gifts and major donors—a select group that includes museums, universities and colleges, high-end performing arts organizations, and hospitals—are already able to attract significant donations. Meanwhile, most nonprofits serving the neediest people in society struggle to raise major gifts. Recognition, rather than impact, is the coin of the development realm.

Third, foundations remain stuck in a “do as we say, not as we do” mode. They demand transparency but share little. They assert the need for impact-based decisions but fail to take the lead by sharing their extensive evaluations of individual nonprofits and of underlying needs. To be sure, organizations such as the Center for Effective Philanthropy, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (through its Philamplify initiative), and the Foundation Center (through its Glasspockets initiative) have undertaken efforts to gather and share foundation data. But on the whole, foundations have minimal incentive or limited means to disclose anything other than the names of board members, asset portfolios, and grantee names and amounts.39

Fourth, funders have still to address the chronic need for sustained operational support. They often seek to fund specific programs that fit their areas of interests. In response, nonprofits present programs that appear to match those areas, perhaps creeping away from their core mission in doing so, and are often left to plead for funding to cover day-to-day operations as overhead. And many younger funders today prefer policy advocacy, innovation, or impact investing, leaving nonprofits that focus on service delivery struggling to fund their core mission.

Fifth, the leadership practices of nonprofit boards remain ineffective. Few boards seek to learn and apply best practices or hold themselves to high standards. Given that government oversight of nonprofits remains essentially limited to cases of outright fraud, effective board governance is a sine qua non for any nonprofit organization, and yet it continues to be the exception.

Sixth, significant differences in performance remain among nonprofit organizations, but the social capital market (i.e., the financial flows from all sources into the sector) does not yet reward high performers or withhold resources from lower performers. Nonprofits often compete in markets dominated by market failure. Consequently, increasing scale and impact often results in worse economics instead of better, thus increasing the need for philanthropy and lessening the reliance on earned revenue. Because most nonprofits are effectively subsidized by donations, subscale and less-skilled organizations can linger, making the economics less attractive for stronger nonprofits. New entrants can hurt even high-impact nonprofits, as can competing subscale organizations that have managed to develop a philanthropic funding base.

Seventh, the sector’s sense of timing and the probability of success have been off. A venture-funded business start-up is expected to provide returns to its investors in, say, five to seven years, or longer—and, as a rule of thumb, only one out of every ten start-ups is expected to account for virtually all of an investor’s return, whereas the other nine will end in death or mediocrity. But in social entrepreneurship, decades may pass before an organization delivers consistent impact or even defines what its impact is. Efforts to instigate social change or provide an important social service, meanwhile, often take decades to become fully effective.

The Need for Increased Philanthropy

Underlying all of these lessons is another insight regarding the course that nonprofit organizations will follow in the Impact Era: in brief, they will need more money, and lots of it.

Let’s recall the basic dimensions of the US nonprofit sector. In total, the sector brings in somewhat more than $1.7 trillion in total revenue.40 That total exceeds the value added by several major US industries, including information technology and communications ($983 billion), retail trade ($969 billion), and banking ($730 billion).41 In aggregate, meanwhile, donations account for 13 percent of nonprofit revenue. Different subsectors rely on donations to different extents. Health care—mostly hospitals—is the largest subsector in dollar terms but differs from most other subsectors in its economics: hospital revenue is roughly half of the nonprofit, charitable sector total. (About 70 percent of inpatient days occur at not-for-profit hospitals.)42 These hospitals in aggregate receive only a small portion of their revenue as donations because private insurance payments and government programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, allow earned revenues to provide a relatively strong financial base. Every other nonprofit subsector needs more than the aggregate average of 13 percent from donations: the next two largest subsectors, education and human services, require 16 percent and 21 percent, respectively.43 The remaining subsectors—international affairs, arts and culture, environment, and religious congregations—rely on philanthropy as their largest source of financial support, ranging from 44 percent for arts to 80 percent for religious congregations.44

Our starting point for calling for more philanthropy—for levels of giving that significantly outpace growth in the sector itself, including growth of other revenue sources—is a problem generally known as the “nonprofit starvation cycle.”45 At its root is a usually implicit, sometimes explicit, lack of trust that nonprofits will spend and invest money well. So funders chronically give them less support than they need, and they endure a hand-to-mouth existence that forces them to adopt a short-term focus and to “cry poor” year after year while also stifling their appetite to try new things. This is hardly appropriate for organizations that exist to serve their communities.

There is nothing new about this starvation cycle. The most cogent summary is offered in “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle,” an article by Ann Goggins Gregory and Don Howard, who cite “funders’ unrealistic expectations,” “underfed overhead,” and “misleading reporting” as the driving factors in this cycle.46 Whatever the root causes, the solution is more generous and more flexible funding by foundations and individuals.

Despite much talk, there has been little progress in addressing those root causes: nonprofits still encounter significant reluctance to fund ongoing operating costs, or the costs of impact evaluation and basic infrastructure. In recent years, as more funders have demanded impact evaluation to demonstrate that interventions are effective, nonprofits have found themselves stuck in a chicken-and-egg situation. Many funders demand impact data but will not fund the often extensive research that is required to provide such data.

Perhaps the most widely debated aspect of the starvation cycle is overhead. In summary, many nonprofits’ financial and accounting systems don’t provide accurate data on overhead costs; ironically, given that many foundations provide support only to fund programs, nonprofits have an incentive to allocate those costs to specific programs. Even with an overhead rate of 20 percent, funders often end up failing to cover a nonprofit’s overhead costs—either because those costs are simply higher than 20 percent or because some donors restrict their gifts to specific types of costs. The negotiation between grantees and grant makers on this issue seems to have become intractable. The starvation cycle has a certain rationality to it: funders, not confident that they know which (if any) organizations are effective at achieving impact, hold back from funding grantees’ full operational needs, perhaps on the assumption that this approach will somehow make the grantees more focused and more disciplined.47

In addition to the sectorwide starvation cycle, specific nonprofit subsectors suffer structural financial challenges, as William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen noted as early as 1966.48 Think of a live orchestra performance: because an orchestra is unable to leverage significant economies of scale—it can sell only so many seats, its costs are largely fixed, and technology has provided no solution—there is no way to increase the productivity of its musicians. As a consequence, major US symphony orchestras, and many other performing arts organizations, have a negative contribution and operating margin—the more performances they play, the more money they lose. The future is clear: such organizations will require more philanthropy.

Funders have been pushing for financial sustainability for the past fifteen to twenty years; in essence, this is a call for more earned revenue. In some cases, when a nonprofit has something of value and a customer base that can pay for that product or service, financial sustainability can be an important part of the solution. GuideStar, for example, originated as a quintessential public good; as of 1996, it derived just 1 percent of its revenue from fees. But since 2010, earned revenue—most of which comes from user fees for premium tools, bulk data licensing, and custom data analysis—has accounted for roughly 85 percent of its total expenditures.49 Stanford Social Innovation Review, similarly, generated between 35 percent and 45 percent of its budget from earned revenue in the years from 2004–2010. More recently, however, it earned nearly 100 percent of its revenue from subscriptions and other nonphilanthropic sources.50

But, by their very definition, many nonprofits provide most or all of their services to people who are in no position to pay. Pressure for earned revenue, moreover, is likely to lead to mission-distracting activities. At the same time, financial sustainability can cause short-termism and restrict an organization’s ability to scale. Look at what has happened to retail banking and retailing companies over the past twenty years: growth, scaling to the national level, leveraging technology. Meanwhile, most US nonprofits that deliver social services remain either local or stuck in a sub-optimal national federation that lacks the investment capital and organizational incentives that only funders could provide—either by modernizing what exists or by supporting the creative destruction process by withdrawing funding from the old model and funding new ones to discover one that leverages technology and new value models.

How much funding will the US nonprofit sector need if it is to remain a robust, sustainable, and essential contributor to civil society? And will philanthropic or other funding match that need? We have conducted an extensive scenario analysis that takes into account multiple factors that will affect the future financial needs of the sector, including costs associated with likely demographic changes (e.g., seniors’ steadily growing share of the population), subsector-specific cost changes, and the potential for increased spending to cover unmet societal needs in the United States and abroad. Our analysis also takes into account the growth in giving that might result from decisions by Giving Pledge signers and other high-net-worth individuals. (The Giving Pledge suggests that signers donate “a majority” of their wealth to philanthropic efforts. But we wonder why 90 percent is not a better target all around. Giving at that level would provide valuable resources to communities, and it would still leave a healthy amount for the givers’ kids!) We modeled various increases in foundation annual grant payouts and various rates of return on investments, as well as various changes in subsector-specific revenue (including shifts in government funding and earned revenue).

Our major conclusion: by 2025, philanthropic donors are on track to contribute between $500 billion and $600 billion annually to the nonprofit sector. (The total for 2015 was $373 billion.)51 In addition, because of growing needs among those who benefit from nonprofit services, as well as urgent needs that remain unmet now, we predict that the nonprofit sector will require between $100 billion and $300 billion annually beyond what it can expect to receive from known revenue sources. (We base this projection both on historical rates of change and on the demographic and cost factors that we discussed earlier.) We believe, therefore, that philanthropy on a scale that exceeds its historical growth rate is the only likely source of significant increased revenue to the sector. Those who think that government funding or earned revenue from insurance payments, admission charges, and so on will increase significantly—we certainly don’t—can reduce this estimate accordingly.

Another conclusion: people in the social sector had better hope that investment returns will at least maintain their levels from the past couple of decades. If investment returns decline meaningfully in the future, perpetual foundations will struggle to meet their federally required 5 percent payout. Universities, museums, and other nonprofits that have grown accustomed to similar payout levels will also find that they face new challenges. Thus, even as the sector requires increased philanthropy, lower investment returns may exert downward pressure on levels of giving.

A Call to Action for the Impact Era: Strategic Leadership

To ensure that these hoped-for new levels of funding will achieve maximum impact, the nonprofit sector must embrace the essentials of strategic leadership.

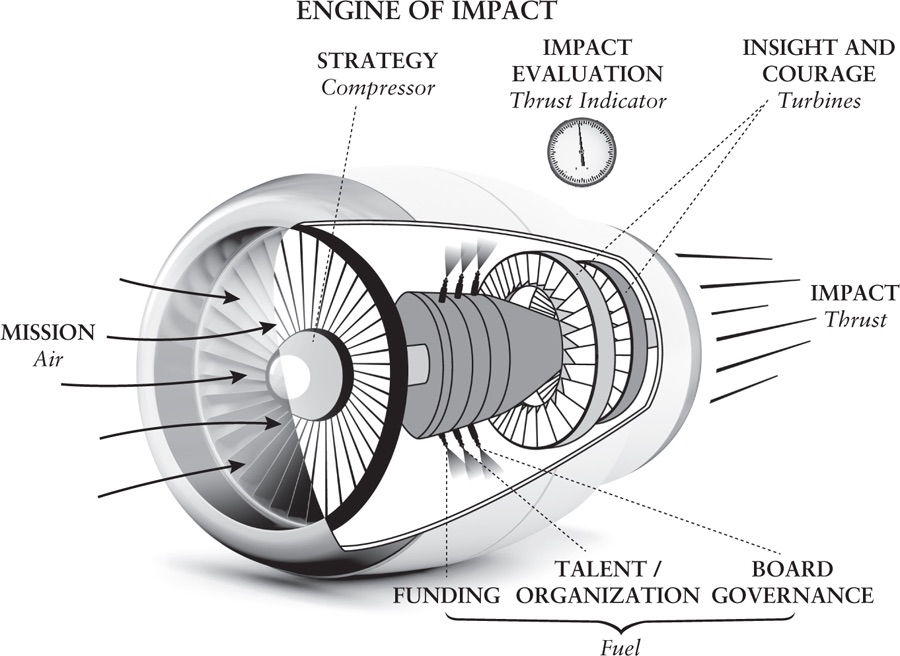

The practice of strategic leadership involves not just doing good work but also doing that work in a highly intentional and highly effective way. The best way to explain this practice, we believe, is by comparing it to a high-performance engine (Figure 1). Like an engine, it consists of multiple components that each must function well in order to ensure that the mechanism as a whole will achieve its purpose. In the model that we have developed, strategic leadership in the nonprofit sector has seven essential components, and success in the sector depends on the ability to operate each component at a high level.

An engine of impact, as we call it, starts with the mission of an organization. That mission is the very air that people in the organization breathe as they do their work. The next essential component is strategy. Much like the compressor in a jet engine, a carefully honed strategy takes the “air” of mission and applies pressure to it; the result is an actionable set of goals that will govern the design and implementation of programs. Impact evaluation functions as the engine’s thrust indicator—as a key instrument to gauge the performance of programmatic work. Impact evaluation allows an organization to compare its performance with its strategic goals, and, through a feedback loop, to adjust and refine its strategy (and on occasion its mission) over time. Helping to generate power for an engine of impact are the twin “turbines” of insight and courage. Those human qualities are what ultimately give an organization its dynamic force. To operate its engine of impact, meanwhile, an organization must draw on three varieties of fuel: well-managed talent and organization, sustained and sufficient funding, and effective board governance. When the engine works well, it creates thrust, or what we call impact.

Of course, the analogy between a nonprofit organization and an engine is inexact. But we offer this comparison to convey a vital truth: To make a significant and lasting impact, nonprofit leaders must engage with all of the essential components of strategic leadership in an integrated and comprehensive way. In particular, they must attain high levels of performance in both strategic thinking (which encompasses mission, strategy, impact evaluation, and insight and courage) and strategic management (which encompasses funding, talent and organization, and board governance). Strategic thinking pivots around a commitment to fact-based problem solving; it allows an organization to build and tune an effective engine of impact. Strategic management involves a keen-eyed focus on execution; it provides the fuel to propel that engine.

Strategic leadership, in short, equals strategic thinking plus strategic management.

Over the course of several decades, we have played virtually every role that exists in the nonprofit sector: executive, donor, grant maker, board member, adviser, even social entrepreneur. And we have been in active dialogue not only with many others who occupy those roles but also with an energetic community of thinkers, writers, speakers, teachers, and observers who work in universities or foundations, or within the sector itself. And on the basis of our extensive experience, we boldly proclaim that strategic leadership remains the most significant source of increased impact for the sector. Regardless of whether one is trying to maximize the impact of a traditional nonprofit or one that is highly innovative, greater impact begins and ends with strategic leadership.

We offer in this book what we believe to be a forward-looking synthesis of the best thinking and the best examples that relate to strategic leadership in the nonprofit sector. The core of the book is built on our own insights. But we have also tried to avoid being proprietary in a sector where virtually all intellectual property is held in common. So we draw freely on what we regard as the best thinking of others. Our goal is to inform and improve the ongoing, vigorous debate over how to maximize the impact of the nonprofit sector overall—and also to help all readers increase the impact of the nonprofits in which they are engaged.

The basic structure of our book is straightforward.

Everything starts with mission. Chapter 1 posits that, despite that central principle, most nonprofits fail to start their strategic thinking process by ensuring that their mission is clear and focused. Having a focused mission statement is a critical tool for fighting “mission creep,” which we believe pervades the nonprofit sector.

To achieve your mission and goals, you need a strategy. Strategy can seem like an arcane discipline that only management consultants and MBAs can understand. In Chapter 2, we describe—in a language accessible to all nonprofit leaders—the strategic concepts (such as theory of change) you need to build your engine of impact.

Rigorous impact evaluation provides critical feedback on whether an organization’s strategy is working. Yet few topics provoke more intense debate than measuring and evaluating impact. In Chapter 3, we offer no simple answers, but we do show that approaches to impact measurement have advanced significantly. We then put forward specific ideas to move impact measurement and evaluation forward as a basis for decision making by nonprofit executives, board members, and philanthropists.

Even though we embrace fact-based analysis, we want to acknowledge that behind every high-impact nonprofit is a leader with exceptional human qualities, starting with insight and courage. This is the topic of Chapter 4. In fact, insight and courage are as essential as a focused mission, a clear strategy, and rigorous impact measurement to a nonprofit’s ability to “earn the right” to seek philanthropic support.

While the first part of the book focuses on the components that you will need to build and tune your engine of impact, the second part of the book is all about fueling this engine. That simply isn’t possible without talent, the subject of Chapter 5. Talent is a critical source of fuel for every organization, but talented people will thrive in an organization only if they have strong and responsive leadership. To this end, we recommend an organizational approach known as “team of teams.” In this chapter, we also review several enduring principles that any high-performing nonprofit organization should follow.

Nonprofit leaders must recognize that if they want to save the world, they have to knock on doors and ask for money. In Chapter 6, we show you how the best fund raisers do it and argue strongly that building a strong major-donor function can provide essential fuel for human service, poverty alleviation, and other types of organizations that traditionally have allowed elite universities and high-end cultural institutions to monopolize that form of philanthropy.

Many in the sector sit on nonprofit boards—and find those boards to be ineffective in some important way. In Chapter 7, we show you how to build and sustain strong board governance. As a process shaped by the behaviors of individuals with varying skills, biases, and personalities, board governance follows no one formula. But an effective board does require leaders to engage more fully and demand more from one another, as well as from executive staff. This chapter provides lessons on how to initiate such engagement.

Along with building a well-tuned engine of impact, nonprofit leaders face another challenge: they must determine how far that engine can take them. They must ask, in other words, whether and how they can scale their organization. Many organizations try to scale too early, before they have “earned the right” to do so by building and tuning their engine of impact. In Chapter 8, we offer a new managerial tool—one that draws on concepts discussed in the preceding seven chapters—that will help nonprofit leaders assess their organization’s readiness to scale.

The essentials of strategic leadership may seem uncontroversial. Yet within the nonprofit sector, they remain subject to widespread neglect. For this book, we conducted a survey—the 2016 Stanford Survey on Leadership and Management in the Nonprofit Sector—that drew nearly three thousand respondents. These respondents play a wide variety of roles in the sector, and they represent virtually every type of nonprofit. We asked them, “What do you think are the top challenges facing the overall nonprofit sector as a whole today (not just your own organization)?” In response, they indicated that the top challenges are (in order of those most cited) “inadequate and/or unreliable measurement/evaluation of organizations’ impact and performance,” “weak or ineffective management,” and “weak or ineffective board governance.”52

By their own admission, moreover, most social sector organizations struggle with at least one essential component of strategic leadership. In our survey, about 80 percent of respondents indicated that their organization faces significant challenges with one or more of these essentials. We believe that an inability to master even one component can prevent an organization from achieving its goals. The chapters that follow serve as a guidebook for conquering such challenges. By using these chapters to help build, tune, and fuel their engine of impact, all social sector organizations can achieve the massive and enduring impact to which they aspire and for which we hope.

1. On hospital care, see Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Hospital Inpatient Days per 1,000 Population by Ownership Type,” data for 2014, http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/inpatient-days-by-ownership/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. On education, see National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), Digest of Education Statistics, table 303.70 (undergraduates) and table 303.80 (postbaccalaureate students), http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_303.70.asp?current=yes and https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_303.80.asp?current=yes.

2. This book focuses largely on US-based nonprofit organizations that register as public charities under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). There are roughly thirty types of tax-exempt nonprofit organizations outlined by the IRC, and 501(c)(3) organizations are the largest of those types; they account for roughly three-quarters of total nonprofit sector revenue. Donors can claim a tax deduction for making a contribution to a charitable organization, but they cannot do so for contributing to most other types of nonprofits, including labor unions, trade associations, and political organizations. In this book, we use the terms charitable organization, nonprofit organization, charity, and nonprofit more or less interchangeably. In each case, we mean entities that are tax-exempt charitable organizations.

3. “Alexis de Tocqueville: From Democracy in America,” chap. 9 in The Civil Society Reader, ed. Virginia A. Hodgkinson and Michael W. Foley (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2003), 123.

4. Ibid.

5. Brice S. McKeever, Nathan E. Dietz, and Saunji D. Fyffe, The Nonprofit Almanac: The Essential Facts and Figures for Managers, Researchers, and Volunteers, 9th ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 2016), 87, figure 5.2, data for 2013; and Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Data: Table 1.3.5—Gross Value Added by Sector,” annual data for 2013, accessed April 27, 2017, http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&904=2013&903=24&906=a&905=2013&910=x&911=0.

6. Lester M. Salamon, S. Wojciech Sokolowski, and Associates, Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Nonprofit Sector, vol. 2 (Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press, 2004), table 5, http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/02/Comparative-data-Tables_2004_FORMATTED_2.2013.pdf.

7. Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

8. Eleanor Brown and James M. Ferris, “Social Capital and Philanthropy: An Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on Individual Giving and Volunteering,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2007): 85–99.

9. John J. Havens and Paul G. Schervish, “A Golden Age of Philanthropy Still Beckons: National Wealth Transfer and Potential for Philanthropy Technical Report,” Boston College Center on Wealth and Philanthropy, May 28, 2014, Table 5, http://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/research_sites/cwp/pdf/A%20Golden%20Age%20of%20Philanthropy%20Still%20Bekons.pdf.

10. Peter Dobkin Hall, “A Historical Overview of Philanthropy, Voluntary Associations, and Nonprofit Organizations in the United States, 1600–2000,” in The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 2nd ed., ed. Walter W. Powell and Richard Steinberg (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 38–39.

11. Paul Arnsberger, Melissa Ludlum, Margaret Riley, and Mark Stanton, “A History of the Tax-Exempt Sector: An SOI Perspective,” Statistics of Income Bulletin (Winter 2008): 106.

12. Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays (New York: Century Co., 1901).

13. “Margaret Olivia Slocum (Mrs. Russell) Sage (1828–1918): Founder of the Russell Sage Foundation,” Auburn University Digital Libraries, accessed November 30, 2015, http://diglib.auburn.edu/collections/sage/essays.html.

14. Karl Zinsmeister, “The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Julius Rosenwald,” Philanthropy Roundtable, accessed April 3, 2017, http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/hall_of_fame/julius_rosenwald.

15. Peter M. Ascoli, Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006), 87. The quote is taken from a speech on May 18, 1911.

16. Peter M. Ascoli, “Julius Rosenwald’s Crusade: One Donor’s Plea to Give While You Live,” Philanthropy (May–June 2006), http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/topic/excellence_in_philanthropy/julius_rosenwalds_crusade.

17. Arnsberger, “History of Tax-Exempt Sector,” 106, 108.

18. Unpublished analysis by Melissa S. Brown (manager, Nonprofit Research Collaborative).

19. “Our History,” United Way, accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.unitedway.org/about/history; and David Rose, “A History of the March of Dimes,” March of Dimes, August 26, 2010, accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/a-history-of-the-march-of-dimes.aspx.

20. Theodore Caplow, Howard M. Bahr, John Modell, and Bruce A. Chadwick, Recent Social Trends in the United States, 1960–1990 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 341.

21. Giving USA Foundation, Giving USA 2003: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2002 (Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2003), 200.

22. Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs (Filer Commission), Giving in America: Toward a Stronger Voluntary Sector (Washington, DC: Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs, 1975), 1, 172.

23. Olivier Zunz, Philanthropy in America: A History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 237; and Filer Commission, Giving in America, 231–233.

24. Filer Commission, Giving in America, 53.

25. Ibid.; and “1973 Filer Commission Defends Private Giving,” Philanthropy Roundtable, accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/public_policy_reform/1973_filer_commission_defends_private_giving.

26. Zunz, Philanthropy in America, 240.

27. Ibid., 242.

28. Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, “Seven Standards of Responsible Stewardship,” accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.ecfa.org/content/standards; and Presbyterian Mission Agency, “Stewardship Manual: A Guide for Year-Round Financial Stewardship Planning,” accessed November 30, 2015, http://www.presbyterianfoundation.org/getattachment/2a2140ca-8ac1–47e5–8c8b-29c66be913a4/PCUSA-Stewardship-Manual.aspx. Both offer examples of contemporary stewardship standards.

29. Cheryl Chasin, Debra Kawecki, and David Jones, “G. Form 990,” Internal Revenue Service (2002), accessed September 21, 2016, http://www.pgdc.com/pdf/CPEtopicg02.pdf.

30. Arnsberger, “History of Tax-Exempt Sector.”

31. “NSF and the Birth of the Internet,” National Science Foundation, accessed July 5, 2017, https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/nsf-net/textonly/90s.jsp.

32. On Ford, see Horace Lucian Arnold and Fay Leone Faurote, Ford Methods and the Ford Shops (New York: Engineering Magazine Company, 1915; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1972), 111. On Carnegie, see Alfred D. Chandler, “The Beginnings of ‘Big Business’ in American Industry,” Business History Review 33, no. 1 (1959): 1–31.

33. Jacob Harold (president and CEO, GuideStar), email correspondence with William F. Meehan III and Kim Starkey Jonker, December 12, 2016.

34. Arthur “Buzz” Schmidt, phone interview by Melissa S. Brown, October 15, 2015.

35. “GuideStar: A Brief History,” GuideStar, accessed November 30, 2015, https://www.learn.guidestar.org/about-us/history.

36. “About Us,” GuideStar, accessed September 22, 2016, https://learn.guidestar.org/about-us.

37. GuideStar, GUIDESTAR 2020: Building the Scaffolding for Social Change, accessed September 27, 2016, https://learn.guidestar.org/hubfs/docs/GuideStar_2020_Strategic_Plan.pdf.

38. Christine W. Letts, William P. Ryan, and Allen S. Grossman, “Virtuous Capital: What Foundations Can Learn from Venture Capitalists,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1997): 36–44.

39. Joel L. Fleishman, The Foundation: A Great American Secret; How Private Wealth Is Changing the World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2007), 262; and Caitlin Duffy, “Lessons in Foundation Transparency from Philamplify,” Transparency Talk (blog), September 22, 2014, http://blog.glasspockets.org/2014/09/duffy-22092014.html.

40. McKeever, Dietz, and Fyffe, Nonprofit Almanac, 87, figure 5.2, data for 2013.

41. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Value Added by Industry,” annual data for 2013, accessed April 27, 2017, https://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=51&step=1#reqid=51&step=51&isuri=1&5114=a&5102=1. The “value added” by an industry is the contribution of that industry to overall US GDP.

42. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Hospital Inpatient Days.”

43. McKeever, Dietz, and Fyffe, Nonprofit Almanac, figures 5.6. and 5.12.

44. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, The 2013 Congregational Impact Study (Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy), 23 (the study reports the median percentage); and McKeever, Dietz, and Fyffe, Nonprofit Almanac, figure 5.4.

45. Ann Goggins Gregory and Don Howard, “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle,” Stanford Social Innovation Review (Fall 2009): 49–53.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid.

48. William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen, Performing Arts—the Economic Dilemma: A Study of Problems Common to Theater, Opera, Music and Dance (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966).

49. Jacob Harold (president and CEO, GuideStar) and Anisha Singh White (strategy manager, GuideStar), email correspondence with William F. Meehan III, February 1, 2016. Data provided by GuideStar and used with permission.

50. Kim Nyegaard Meredith (executive director, Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society), email correspondence with William F. Meehan III, January 31, 2016.

51. Giving USA Foundation, Giving USA 2016: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2015 (Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2016).

52. William F. Meehan III and Kim Starkey Jonker, 2016 Stanford Survey on Leadership and Management in the Nonprofit Sector, Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2016, engineofimpact.org/survey.