At the antipodes of the monarchical principle, in theory, stands democracy, denying the right of one over others. In abstracto, it makes all citizens equal before the law. It gives to each one of them the possibility of ascending to the top of the social scale, and thus facilitates the way for the rights of the community, annulling before the law all privileges of birth, and desiring that in human society the struggle for preëminence should be decided solely in accordance with individual capacity.

—Robert Michels (1915, p. 1)

On April 1, 2000, Prime Minister Obuchi Keizō of the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) of Japan suffered a sudden stroke at the age of sixty-two and later died following a monthlong coma.1 As prime minister, Obuchi had been described as having “all the pizazz of a cold pizza” because of his bland personality and style.2 However, as a candidate for the House of Representatives, the lower and more powerful chamber of Japan’s bicameral parliament, the National Diet, he had been extremely successful. Obuchi’s father had been a member of parliament (MP) in the House of Representatives for Gunma Prefecture’s 3rd District until his death in 1958. In 1963, at the age of twenty-six, Obuchi ran for his father’s old seat and won his first election. He went on to win eleven consecutive reelection victories, and earned more than 70 percent of the vote against two challengers in his final election attempt in 1996.

In the June 25, 2000, general election held shortly after his death, the LDP nominated Obuchi’s twenty-six-year-old daughter, Yūko, as his replacement. Yūko had quit her job at the Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS) television network to become her father’s personal secretary when he became prime minister in 1998. In her first election attempt, she defeated three other candidates with 76 percent of the vote. Since then, she has consistently won between 68 percent and 77 percent of the vote in her district and has faced only weak challengers from minor parties. The LDP’s main opposition from 1998 to 2016, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), fielded a candidate against her only in the 2005 general election: a thirty-six-year-old party employee with no prior electoral experience.3 He managed to win only a quarter of the vote in the district.

A young and politically inexperienced woman like Obuchi Yūko would normally be considered a weak candidate in Japan, where the average age of first-time candidates is forty-seven, and female candidates are rare (Obuchi was one of just five women nominated in a district race by the LDP in the 2000 election). Yet by virtue of her family background, and no doubt aided by sympathy votes after her father’s death, she enjoyed an incredible electoral advantage in her first election—both in terms of her name recognition with voters and in terms of the lack of high-quality challengers—and this advantage continued in subsequent elections. In 2008, after just three election victories, she became the youngest cabinet minister in postwar Japanese history when she was appointed minister of state in charge of the declining birthrate and gender equality in the cabinet of Prime Minister Asō Tarō. Few other LDP MPs have advanced to positions of power in the cabinet as quickly.

The Puzzle of Dynasties in Democracies

This book is about the causes and political consequences of dynasties in democracies. It examines the factors that contribute to their development over time and across space, and the advantages that members of dynasties, such as Obuchi Yūko, enjoy throughout their political careers—from candidate selection, to election, to promotion into higher offices in cabinet. It also considers the potential consequences of dynastic politics for the functioning of modern representative democracy. More specifically, the research design employed in this book takes advantage of institutional change in the country of Japan to help shed comparative light on the phenomenon of dynasties across democracies more generally. The aim is to improve our understanding about how dynastic politics have evolved over time in Japan, as well as how Japan’s experience might provide insight or lessons for understanding dynastic politics in other democracies around the world.

How might we conceptualize “dynasties” in democracies? Dynasties are, of course, common at the executive level in nondemocratic regimes such as monarchies or personal dictatorships. An autocratic ruler can often successfully anoint a family member as his (it is almost always “his”) successor when the party system or leadership selection mechanisms are weak, and the extant power distributions among the broader elite are sustained (Brownlee, 2007).4 An example is North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, who came into power in 2011 as the “Great Successor” to his deceased father, Kim Jong-il, who himself became supreme leader following the death of his father, Kim Il-sung, in 1994. Another example is Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, who inherited his position in 2000 from his father, Hafez al-Assad, who had ruled Syria in a personal dictatorship since 1971.

But that similar dynasties should continue to exist in democracies seems to run counter to widely held normative visions of democratic opportunity and fairness—even given the fact that members of dynasties must ultimately be popularly elected. The democratic ideal that “all men are created equal” should presumably extend to the equality of opportunity to participate in elective office, such that no individual is more privileged simply by birth to enter into politics. We might therefore expect democratization to catalyze an end to dynasties, as all real democracies eventually provide for the legal equality of all citizens to run for public office, barring minor restrictions based on place of birth, residence, age, or law-abiding conduct. Even before full democratic reform, modernization and the rise of capitalism should contribute to the decay of the traditional patrimonial state, such that historically dominant families should begin to “fade from macropolitics” (Adams, 2005, p. 29).

And yet throughout the modern democratized world, it is still possible to find powerful political dynasties—families who have returned multiple individuals to public office, sometimes consecutively, and sometimes spanning several generations. It is not uncommon for parties and voters to turn to “favored sons,” “democratic scions,” or the “People’s Dukes” for political representation, despite the availability of less “blue-blooded” candidates.5 Recent prominent examples from outside of Japan include President George W. Bush and Senator Hillary Clinton in the United States, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in Canada, Prime Minister David Cameron and Labour Party leader Ed Miliband in the United Kingdom, President Park Geun-hye in South Korea, Marine Le Pen and Marion Maréchal-Le Pen in France, Prime Minister Enda Kenny in Ireland, President Benigno Aquino III in the Philippines, Sonia and Rahul Gandhi in India, Alessandra Mussolini in Italy, and Tzipi Livni in Israel.

Defining what exactly constitutes a dynasty can be complicated given the variety of family relationships and levels of government in which family members might serve. In this book, a legacy candidate is defined as any candidate for national office who is related by blood or marriage to a politician who had previously served in national legislative or executive office (presidency or cabinet). If a legacy candidate is elected, he or she becomes a legacy MP and creates a democratic dynasty, which is defined as any family that has supplied two or more members to national-level political office.6 This definition of what constitutes a dynasty is more liberal than that used by Stephen Hess (1966, p. 2), who defines a dynasty in the American context as “any family that has had at least four members, in the same name, elected to federal office.” The definition used here is not limited to dynasties with continuity in surname. In addition, only two family members are necessary to constitute a dynasty, rather than four members, which would limit the scope of the analysis to countries, such as the United States, with a longer democratic history. The definition also does not require that a legacy candidate be a member of the same party as his or her predecessor, or run in the same electoral district, although both conditions generally tend to be the case. Family members can serve consecutively or simultaneously, with the exception that two family members first elected at the same time would not constitute a democratic dynasty.

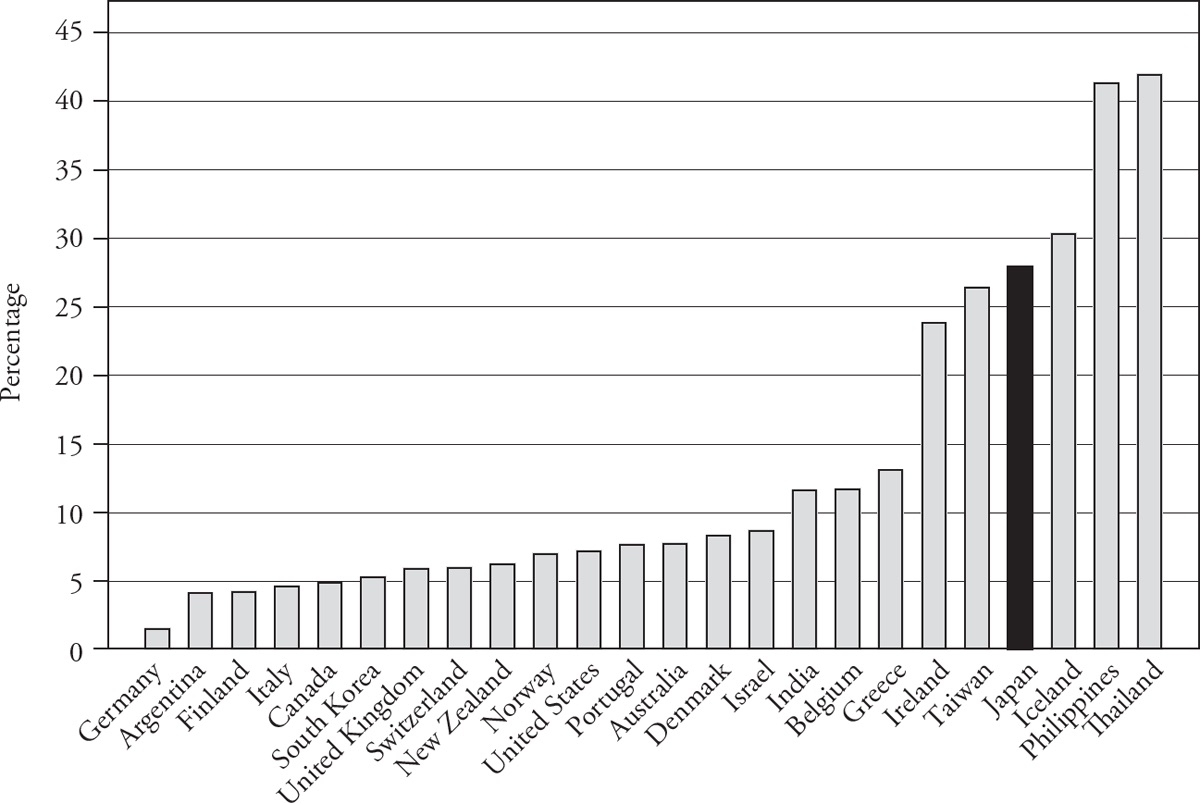

By this definition, Japan stands out among democracies for its high proportion of legacy MPs. Figure 1.1 shows the average percentage of legacy MPs among all MPs elected in the past two decades (1995–2016) in twenty-four democracies for which data are available. Since the 1996 general election, more than a quarter of all MPs in the Japanese House of Representatives have been members of a democratic dynasty, a fact that puts Japan, along with Ireland and Iceland, in the company of economically developing and younger democracies like Taiwan, the Philippines, and Thailand (the most dynastic country for which data are available). Greece, Belgium, and India occupy what might be considered the middle stratum of dynastic politics, with between 10 percent and 15 percent of members in recent years coming from democratic dynasties.7 In most other democracies, legacy MPs tend to account for between 5 percent and 10 percent of parliament. This level of dynastic politics might thus be considered a “normal” level for healthy democracies. Among the democracies for which comparative data are available, Germany appears to be the least prone to dynastic politics, with less than 2 percent of members of the German Bundestag in recent years counting as legacy MPs.

What accounts for this variation across democracies, and for the high level of dynastic politics in Japan? It is perhaps unsurprising that dynasties might abound in nascent and developing democracies, where the economic rents from political office are often greater than the opportunities for riches outside of public office. If access to political decision-making authority enables politicians to live considerably better than their constituents, then this should provide greater incentives for such elites to seek to maintain their grip on power. The pool of elites who are interested, eligible, and qualified for public office may also be shallower in new and developing democracies. Members of the elite ruling class may be among the few with the education, wealth, and other technical skills and resources necessary to be effective candidates and policymakers.

Similarly, a lower supply of high-quality non-legacy candidates might help to explain a high proportion of dynasties in small democracies such as Iceland. The Icelandic Althingi contains just sixty-three seats and represents a population of only about 320,000 people (more than half of whom live in and around the capital of Reykjavík). A smaller-sized parliament also means that even a small increase or decrease in the raw number of legacy MPs can mathematically have a big effect on the overall proportion in parliament.8 We might expect to find similarly high proportions of dynasties in other small countries, such as the island democracies of the Pacific and Caribbean. For example, President Tommy Remengesau Jr. of Palau is the son of a former president, and Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga of Tuvalu is the brother of a former prime minister.

However, economic development in larger democracies should be expected to eventually lead to a decline in dynasties, in part because it should broaden the structure of political opportunity so that a more diverse range of citizens will be qualified and able to get involved in politics, including through direct participation in elective office. The development of competitive and programmatic political parties should further limit the power of dynasties and increase the opportunities for capable outsiders to enter politics. Indeed, in nearly all established democracies, the trend over time has been a decrease in dynasties since democratization.9 In the United Kingdom, for example, the proportion of legacy MPs in the House of Commons declined from more than 30 percent in the late 1800s to less than 10 percent in recent decades (van Coppenolle, 2017). The proportion in the Swiss National Council peaked at around 19 percent in 1908, then gradually dropped to less than 6 percent by the 2000s. In Italy, the proportion of legacy MPs in the Chamber of Deputies declined from roughly 13 percent in the immediate postwar period to less than 5 percent today. Dynastic membership in the Canadian House of Commons reached its zenith of 11 percent in 1896, and today is also less than 5 percent.

In the United States, despite several high-profile legacy candidates among presidential hopefuls in recent decades—such as Al Gore, George W. Bush, Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush, Hillary Clinton, and Rand Paul—the general trend in Congress has also been a decline in dynasties.10 In the early decades of American democracy, over 15 percent of members of the House of Representatives were related to a previous member of Congress (either chamber) or the president. However, in recent decades, members of such dynasties have accounted for only around 6 percent to 8 percent of members (Dal Bó, Dal Bó, and Snyder, 2009; Feinstein, 2010). Dynasties have elicited a considerable amount of attention in the US media in recent years, but their prevalence in Congress is actually comparable to the prevalence of dynasties in most other developed democracies.

In striking contrast, Japan witnessed a steady increase in dynasties for several decades following democratization. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, the US Occupation (1945–1952) introduced universal suffrage and equality of eligibility for public office, and enshrined these rights in the postwar Constitution of 1947.11 Since then, despite rapid economic growth and the legal opportunity for all citizens to participate in politics, the proportion of legacy MPs in the Japanese House of Representatives subsequently crept upward, toward a zenith of over 30 percent by the late 1980s. Dynasties have been particularly prevalent within the conservative LDP, which has been the dominant party in Japan since its formation in 1955. Over time, the proportion of dynasties in the LDP swelled—from less than 20 percent of elected members in 1958, the first election after the party’s founding, to over 40 percent by the early 1980s. Moreover, nearly half of all new candidates for the LDP in the 1980s and early 1990s were legacies.

In contrast, the share of legacy MPs in the Japan Socialist Party (JSP), the LDP’s main opposition on the left until 1993, rarely exceeded 12 percent. In the third largest party, the religious party Kōmeitō, the average was just 5 percent. In the center-left DPJ, the proportion was initially over 25 percent, owing to the numerous former centrist members of the LDP who joined the party after it was founded in 1996. However, the DPJ subsequently recruited fewer new legacy candidates, and the proportion of legacy MPs in the party declined to around 16 percent. As a result, when the DPJ won a landslide victory over the LDP in 2009, the proportion of legacy MPs in the House of Representatives dropped to 22 percent—still high by comparative standards but the lowest proportion in Japan since the 1960s. In the 2014 House of Representatives election, 156 out of 1,191 candidates were legacy candidates (13 percent); however, 125 of these legacy candidates won, so legacy MPs accounted for 26 percent of the 475 MPs in the chamber. Ninety-eight (78 percent) of these legacy MPs were members of the LDP.

Such a disproportionately large presence of dynasties in a long-established and economically advanced democracy like Japan runs counter to our expectations for how the nature of political representation develops over time in democracies, as well as widely held normative visions of democratic opportunity and participation—particularly when the trend over time is toward more dynasties rather than fewer. Elections in Japan are free and fair, and the country does not suffer from the severe economic inequality or lack of social mobility and access to higher education that may pose barriers to greater participation of non-legacy candidates in developing democracies. With a population of over 120 million people, it is also difficult to believe that there are simply not enough willing or qualified non-legacy candidates available to run for public office.

How have dynasties managed to persist and multiply, particularly within the LDP, despite the lack of formal barriers to candidacy for all eligible citizens? What is it about democratic dynasties like the Obuchi family that allows them to thrive across multiple generations in an advanced industrialized democracy like Japan? Do legacy candidates possess special advantages, such as name recognition, familiarity with politics, or financial resources above and beyond those of other candidates, which make them more capable of “succeeding” in politics (in both senses of the word)? If so, what are the conditions under which these advantages become more or less pronounced? And what are the potential consequences of dynastic politics for the functioning of democracy and the quality of representation in Japan?

These are the kinds of questions that will be tackled in this book. By examining the phenomenon of democratic dynasties through the case of Japan, the goal is to shed comparative light on two broader puzzles: First, what are the underlying causes of dynastic recruitment and selection in democracies? Second, what are the political consequences of dynastic politics for the functioning of elections and representation?

Why Dynasties? The Causes of Dynastic Politics

One explanation for the phenomenon of democratic dynasties points to the dominance of elites in political life more generally. Scholars of political elites and power have long argued that the ruling class of a society can perpetuate its status over the less organized masses, even within a democracy (e.g., Michels, 1915).12 The wealth, network connections, and other resource advantages of the elite help them to win elections, and these advantages are often easily transferred to their children, either directly or by virtue of increased opportunities for education and career advancement from the environment of their childhood. Gaetano Mosca (1939, pp. 61–62) provides an elaboration of this point:

The democratic principle of election by broad-based suffrage would seem at first glance to be in conflict with the tendency toward stability which . . . ruling classes show. But it must be noted that candidates who are successful in democratic elections are almost always the ones who possess the political forces above enumerated [resources and connections], which are very often hereditary. In the English, French and Italian parliaments we frequently see the sons, grandsons, brothers, nephews and sons-in-law of members and deputies, ex-members and ex-deputies.

With a few exceptions, such as the Kennedy family, the most prominent dynasties in US history have shared a more or less common background that might be considered the “best butter” in American politics: “old stock, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, professional, Eastern seaboard, well to do” (Hess, 1966, p. 3). Similarly, it is common for members of Japanese dynasties to have advanced degrees from the finest universities (or to have studied abroad), and many come from wealthy backgrounds. For example, brothers Hatoyama Yukio and Kunio were heirs to the Bridgestone Corporation fortune through their mother.13 Even in democracies, elite families might continue to dominate the political process simply by virtue of their superior endowments of income, education, and connections. These advantages might arguably give legacy candidates a head start over non-legacy candidates in building a political career.

This type of elite dominance theory for dynastic politics is likely to have the most power in explaining dynasties in developing democracies, where political elites typically enjoy higher standards of living than their constituents and political parties play a smaller role in organizing and financing political competition. In the Philippines, for example, jurisdictions represented by legacy MPs tend to be associated with higher poverty, lower employment, and greater economic inequality (Mendoza et al., 2012; Tusalem and Pe-Aguirre, 2013). A high proportion of dynasties has also been documented in developing democracies in Latin America, such as Mexico (Camp, 1982) and Nicaragua (Vilas, 1992), and in South Asian developing democracies like India (Chhibber, 2013; Chandra, 2016) and Bangladesh (Amundsen, 2016).

If holding political office brings private rents that exceed what might be gained in other professions, elite families might also try to hold on to power through direct manipulation of the electoral or candidate selection processes. For example, Pablo Querubín (2011) finds that term limits in the Philippines do not stop the perpetuation of dynasties—rather, they allow them to spread because politicians tend to seek higher office and get their relatives elected to their previous positions. Pradeep Chhibber (2013) looks at dynastic succession in party leadership in India through a similar lens. He argues that dynastic leadership succession is more likely in parties that lack broader organizational ties to groups in society and have centralized party finances in the top leadership. Such personalized parties might be compared to family firms, with incentives to keep leadership and control of the party within the family (as well as knowledge of any financial malfeasance). Kanchan Chandra (2016) makes a similar argument about access to state resources and weak party control over nominations to explain the Indian case, but she considers all MPs elected to recent parliaments, not just party leaders.

THE INHERITED INCUMBENCY ADVANTAGEIn contrast to prior research on dynasties in developing democracies, the existing research on dynasties in developed democracies has focused more specifically on the electoral and informational advantages of a dynastic background. Legacy candidates enjoy strong name recognition, network connections, ease in raising campaign funds, and familiarity with politics and campaigning through increased exposure to the political life of family members, and this may result in their being favored over non-legacy candidates in the recruitment and selection processes. These advantages are much like the well-known advantages enjoyed by incumbents.

The incumbency advantage in US congressional elections, and its growth over time, has been widely studied since it was first pointed out in the early 1970s (Erikson, 1971; Mayhew, 1974). The source of the incumbency advantage has been divided in the existing literature into three main components: (1) the direct advantages of being in office (e.g., increased name recognition, perquisites of office, and the ability to direct funds to one’s district), and indirect advantages owing to (2) the differential quality of incumbents due to on-the-job experience, and (3) the deterrence of high-quality challengers. These components of the incumbency advantage can be a challenge to disentangle, as some might reflect ex ante qualities that helped a candidate win election in the first place, whereas others can be considered the result of the “treatment” of winning office. Recent studies have aimed to estimate the causal effect of incumbency on future election outcomes through the use of regression discontinuity (RD) designs applied to close elections, where the treatment of winning office can be considered “as good as randomized” (Lee, 2008).14 The conclusion from most of these studies is that marginally elected incumbents tend to enjoy significantly higher probabilities of being renominated and reelected in future races. Comparative studies have identified a similar incumbency advantage in a wide range of countries and contexts.

It is not difficult to imagine how a legacy candidate, particularly one who immediately succeeds his or her family member as a candidate in the same electoral district, might “inherit” part of a predecessor’s incumbency advantage, both in terms of concrete electoral advantages (name recognition, connections, and resources) and—because of those perceived electoral advantages—in terms of candidate selection. The advantages enjoyed by a new legacy candidate as a result of his or her family ties to a previous politician can be regarded as an inherited incumbency advantage.

In a seminal study of dynasties in the US Congress, Ernesto Dal Bó, Pedro Dal Bó, and Jason Snyder (2009) reject the idea that dynastic persistence reflects differences in innate family characteristics (what we might call the “best butter” argument for elite dominance) and argue that the probability of a dynasty forming increases with the length of time a founding member holds office—suggesting a “power-treatment effect” acting on the ability of dynasties to self-perpetuate. In other words, dynasties become more likely to form as a (potential) founding member builds up what is likely to be a greater incumbency advantage. Although holding office for several terms should not necessarily affect the innate personal characteristics of a politician’s child or other close relative, it most certainly increases his or her political connections, familiarity with election campaigns and the policymaking process, and name recognition. These positive effects of officeholding may thus help perpetuate an elite family’s status in politics. The implication, as Dal Bó, Dal Bó, and Snyder (2009, p. 115) put it, is that “power begets power.”

In most cases of dynastic succession in politics, the aspect of the incumbency advantage that is most easily heritable is name recognition. Similar to affiliation with a party label, family names can function as “brands” that convey information to voters at a low cost, helping to cue the established reputation of the family (Clubok, Wilensky, and Berghorn, 1969; Feinstein, 2010). They can be especially valuable when party labels are a weak source of information. If personal reputation is important to garnering votes, candidates whose relatives had served in politics can capitalize on the name recognition and established support inherited from their relatives. Name recognition can help a legacy candidate get selected, and elected, even if he or she enters the political scene several years after a predecessor’s exit from politics. It can also play a role in the selection of a legacy candidate following the sudden death of an incumbent, with party elites hoping to capitalize on any possible sympathy vote in the resulting by-election. Nominating a relative in such cases may even be viewed as closely approximating the wishes of the electorate that had previously given a mandate to the now-deceased politician.

Previous studies of dynastic politics in Japan have also emphasized the importance of name recognition in elections that are centered more on candidates’ personal characteristics and local ties than on their party labels or policies (e.g., Ishibashi and Reed, 1992; Taniguchi, 2008).15 Michihiro Ishibashi and Steven R. Reed (1992) note that a legacy candidate in Japan benefits not only from name recognition but also from the connections his or her predecessor built to influential people in the party hierarchy, and to financial backers, which may help secure a party nomination. Even when a legacy candidate does not share the same name—for instance, in the case of a son-in-law, or a daughter who has married and taken a new surname—he or she might still benefit from the political capital (e.g., connections, financial resources) built up by a predecessor over the years.

At the most basic level, the persistence of dynasties in Japan and other democracies might therefore be explained by the inherited incumbency advantage enjoyed by legacy candidates and the effect that this advantage has on voters and party elites involved in candidate selection. However, the fact that there is variation across countries and parties, as well as variation over time, suggests that something is missing in the “power begets power” theory of dynasties. First, why do dynasties seem to be so much more prevalent in Japan than in other developed democracies? In other words, if there is a power-treatment effect of incumbency, why has it apparently been so much stronger in Japan than elsewhere? Second, why is there so much variation in the proportion of legacy candidates in different parties in Japan? Party differences within democracies cast doubt on the simplicity of the power-begets-power theory, as well as any explanation for dynasties that rests solely on country-level explanations, including ones that might point to history or culture as determinants of dynastic politics. A complete understanding of the causes of dynastic politics in democracies like Japan must account for differences at several levels of analysis, including country, party, district, and individual politician.

A further limitation of existing studies of democratic dynasties is that they often only analyze winning candidates (i.e., congresspersons or MPs) or measure trends in dynastic recruitment within a single institutional context. The problem with analyzing winning candidates is the inability to disentangle the attractiveness of legacy ties in the candidate selection stage from the electoral advantages enjoyed by legacy candidates once they are chosen (i.e., the roles of party elites versus voters in the perpetuation of dynasties). The problem with analyzing a single institutional context is the difficulty in evaluating the external validity of the theory and empirical findings. This is especially true given that much of the previous theoretical research on dynasties has focused on the candidate-centered US context, where candidates are chosen in primary elections by voters (thus removing the direct influence of party elites from the equation).16 In most other democracies, parties exercise control over candidate selection.

Comparative models of candidate selection suggest that within a given institutional context, there are supply and demand reasons behind the emergence of individual candidates for office (e.g., Norris, 1997; Siavelis and Morgenstern, 2008). Why, then, might some countries feature a higher supply of legacy candidates? On the flip side, why might there be greater demand for such legacies in the candidate recruitment and selection processes of some parties? If the supply of legacy candidates were related only to the existence of capable offspring of incumbent politicians, then we would expect to see such legacy hopefuls in ample supply across all democracies. After all, politicians in all democracies are capable of producing or adopting children who could potentially succeed them as candidates, and most also have more distant relatives such as nephews and nieces. Likewise, if being a legacy candidate offered the same electoral advantages across all democracies, then we should expect to see equal demand for such candidates from the actors involved in the candidate recruitment process. The comparative empirical record suggests that neither is the case.

A COMPARATIVE INSTITUTIONALIST APPROACHThis book offers an explanation for variation in dynastic politics across democracies and parties that focuses attention on the institutional factors affecting the supply and demand incentives in candidate selection. In brief, the argument is that dynastic candidate selection will be encouraged in institutional contexts that increase the perceived value of a potential candidate’s inherited incumbency advantage, and decrease the ability or desire of national party leaders to control the selection process. While all democracies are likely to feature some amount of dynastic politics, particularly in the early years following democratization, certain institutional features can facilitate and even encourage the formation of dynasties by increasing the electoral value of the inherited incumbency advantage. At its core, this explanation rests upon assumptions about the role that institutions play in structuring political behavior. It is useful, therefore, to provide a brief overview of this theoretical framework.

Institutions are humanly devised constraints, rules, or standard operating procedures that structure the behavior of political actors such as voters, candidates, and party leaders (North, 1990; March and Olsen, 1984). Formal institutions are laws or written codes governing political behavior, and they include the constitutional structure of the state (e.g., separation of powers), electoral rules, and sometimes the candidate selection procedures within parties. Informal institutions, in contrast, encompass the norms, conventions, and other unwritten rules that are routinely practiced and expected by political actors. Examples of informal institutions include the routine renomination of incumbent politicians, the seniority system for promotion to higher office, and the proportional allocation of cabinet portfolios to factions or parties in a coalition government.

Institutions are generally regarded as “sticky,” meaning that they are relatively stable and resilient to changes in the individual actors operating under their constraint. One of the advantages of this stickiness is that institutions can be useful for predicting the equilibrium behavior of political actors operating within those systems. The analytical use of institutions to explain and predict equilibrium behavior has been a key feature of the rational choice approach within the so-called new institutionalism perspectives in political science (Hall and Taylor, 1996). In short, the rational choice approach assumes that individual actors—be they voters, candidates, or party leaders—have clear and transitive preferences over outcomes, and when given the opportunity and agency to make a choice, these actors can be expected to pursue the choice that will maximize the chances of achieving their preferred outcomes. Institutions are critical components of this approach because they serve as coordination mechanisms, helping to structure incentives, constrain choices, and increase certainty about the strategic behavior of other actors in the same system.

However, as with all humanly devised constraints, institutions are sometimes subject to change—either piecemeal, with new layers and conditions being added to old ones, or wholesale, with entirely new arrangements and concomitant behavioral incentives introduced (Streeck and Thelen, 2005). The most dramatic mode of institutional change, complete displacement of one set of rules with another, can be conceived of as either occurring exogenously (i.e., precipitated or imposed by some external source or pressure), or endogenously (i.e., purposefully designed by the actors currently operating in the system).17 Whether to treat institutional change as exogenous or endogenous is an analytical question that must be considered by the researcher. For rational choice proponents who are interested in formalizing predictions for equilibrium behavior under a set of institutions, it is often useful to view institutional change as an exogenous shock that displaces the prior institutions with new ones and produces incentives for a new behavioral equilibrium. This can often be a useful approach in research that uses quantitative data, as outcomes of interest can be measured and the average effects of institutional changes can be estimated via statistical tools. Several studies based on a rational choice approach have been influential in reshaping conventional wisdom in the study of Japanese politics (e.g., Ramseyer and Rosenbluth, 1993; Cox, 1994). A recent example of a perspective inspired by rational choice is Frances Rosenbluth and Michael Thies’s (2010) overview of how electoral reform and other changes of the 1990s have transformed Japan’s politics and political economy.

In contrast, proponents of the historical institutionalist approach—a second approach within the “new institutionalism” perspectives—tend to prefer a more nuanced analysis of institutions and behavior that endogenizes their creation and impact. Historical institutionalists often use qualitative methods to evaluate the temporal sequence and process through which institutions evolve and change. When institutional change does occur, behavioral patterns from a previous institutional regime can linger or persist, often with adaptation, as a reflection of path dependence (Pierson, 2004). In other words, institutional change does not necessarily create a tabula rasa for political behavior—often the very actors who effected the change continue to exist and operate under the new rules, and the historical legacy of the past cannot be easily discarded. Moreover, the institutions that precede any kind of institutional change are likely to influence the nature and components of the new institutions. A recent application of the historical institutionalist approach to understand Japanese politics is Ellis Krauss and Robert Pekkanen’s (2011) examination of how the LDP adapted its existing internal party structures to suit new pressures and challenges following electoral reform in 1994.

The rational choice approach and the historical institutionalist approach both tend to view institutional change as rare moments, or “critical junctures,” where the existing stickiness of the system is opened up to both agency and choice (Mahoney and Thelen, 2009, p. 7). The difference in the approaches often boils down to the objectives of the researcher. What are the outcomes of interest, and how can we measure them? Do we want to understand what sorts of behavior we might expect to observe in equilibrium under a given set of institutions, even if this comes with the cost of some level of abstraction? Or do we want to understand the more detailed nuances of how certain behaviors persist or evolve over time following an institutional change?

The examination of dynastic politics in this book includes elements of both the rational choice and the historical institutionalist approaches, and draws on both quantitative and qualitative data—in other words, it is a mixed-methods or multimethod approach (Seawright, 2016). Many of the conceptual terms just introduced are relevant later in the book in interpreting how Japan’s dynastic politics have evolved in response to institutional change. The comparative theory introduced for understanding the causes of dynastic politics is more in the tradition of a rational choice approach to predicting the expected equilibrium behavior under different institutions (although the formal language of many rational choice models is avoided). However, the analysis takes an approach more in the tradition of historical institutionalism when evaluating the adoption of institutional reforms and the adaptation of political actors over time in Japan. This combined approach lends itself to the use of quantitative and qualitative data and methods. In addition to extensive quantitative data on candidate characteristics, election results, and legislative behavior, the analysis in each chapter draws on personal interviews with politicians and party organization staff from the major parties in Japan. The hope is that such a combination of data and approaches will paint a more complete picture of how institutions influence the practice of dynastic politics, as well as the impact of key institutional reforms in Japan.

THE ARGUMENT IN BRIEFThe theory proposed in this book for understanding democratic dynasties is based on a supply-and-demand framework of candidate selection. On the supply side, potential legacy candidates will be more likely to want to run for office if their predecessors had served longer tenures in office, allowing them greater time to be socialized into a life of politics. In addition, potential legacy candidates will be more likely to want to run if the family already has a history of multiple generations in politics. However, these supply-side incentives can be assumed to be relatively universal across countries and parties. To explain the observed variation across country and party cases, the theory posits a demand-side interaction between the inherited incumbency advantage of a potential legacy candidate and factors that increase or decrease what can be thought of conceptually as a dynastic bias in candidate selection.

Of these demand-side factors, the argument of this book is that the institutions of the electoral system and candidate selection process within parties are key contributors to the observed patterns in dynastic recruitment in democracies. This is not to say that other factors, such as population size, age of the democracy or party, level of economic development, political culture, or other variables, do not play some role in dynastic politics. The nature of a party’s organizational base, and idiosyncratic events like a politician’s death in office, can also play an important part in determining the supply and demand for legacy candidates. However, the influence of these factors can be significantly constrained or enhanced by the institutional context of elections and candidate selection.

The electoral system is the set of rules that determines how votes are cast and counted to determine the winner(s) of elections for public office. It is therefore the key institution for aggregating voter preferences in modern representative democracies. However, the ways in which votes are cast and counted across different electoral systems can have profound impacts on the nature and functioning of representation. Most important, electoral systems that require voters to choose a candidate, rather than a party, tend to generate incentives for voters to focus on the personal attributes and behavior of candidates (Carey and Shugart, 1995). The personal vote is a “candidate’s electoral support which originates in his or her personal qualities, qualifications, activities, and record” (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina, 1987, p. 9). It stands in contrast to a vote cast strictly for a party and the policies it represents. The implication of the personal vote for representation is that in candidate-centered systems (where the personal vote matters more than the party vote), the individual candidate, rather than the collective party, is perceived to be the primary agent of representation for voters. Candidate-centered electoral systems thus tend to emphasize direct accountability and responsiveness of individual candidates to voters, in contrast to accountability based on voters’ evaluation of the programmatic goals and performance of parties (Carey, 2009).

Under candidate-centered systems, party leaders face a potential trade-off in candidate selection decisions. Leaders must balance the utility they can get from each potential candidate in terms of three main party priorities: vote seeking, policy seeking, and office seeking (Strøm, 1990). Although a candidate with a strong personal vote may be more likely to earn an extra seat for the party, that individual strength might allow him or her to dissent from the party’s preferred legislative policy priorities with greater impunity. A party may sometimes prefer to nominate a candidate who has a weaker personal vote but who contributes to the party’s image or policy goals as a loyal agent of the party. But doing so also comes with the risk of losing the seat. The outcome of these competing incentives in candidate nomination decisions will depend on the relative electoral value of the personal vote. The implication for dynastic politics is that electoral systems that generate stronger incentives for candidate-centered (rather than party-centered) vote choice will increase the relative value of the inherited incumbency advantage as a personal-vote-earning attribute, both for voters and for party actors involved in candidate selection. Thus, the demand for legacy candidates will be higher, on average, under candidate-centered electoral systems than under party-centered electoral systems.

However, even within the same electoral system context, the candidate selection process within parties can also have an influence on the practice of dynastic politics. Candidate selection can be defined as the “process by which a political party decides which of the persons legally eligible to hold an elective office will be designated on the ballot and in election communications as its recommended and supported candidate or list of candidates” (Ranney, 1981, p. 75). In practice, the structure and process of candidate selection can vary across parties, even under the same electoral system. Reuven Hazan and Gideon Rahat (2010) identify four dimensions in candidate selection institutions: candidacy (i.e., who is eligible to run), the selectorate (i.e., who decides the nomination), the appointment or voting system (i.e., through which voting rules nomination decisions are made), and decentralization (i.e., whether the decision is made centrally or locally). Variation on each of these dimensions can produce different outcomes in the types of candidates who are selected and their behavior once in office.

Of the potential institutional dimensions of candidate selection, the argument in this book is that the level of inclusiveness in candidate eligibility and the degree of decentralization in the process are likely to have the greatest influence on dynastic politics. Put simply, a more inclusive candidate pool provides parties with a greater supply of potential non-legacy candidates. Nevertheless, whether or not party leaders make use of those candidates may also depend on the hierarchical level at which selection takes place within the party. All else being equal, in parties where the candidate selection process is decentralized to local party actors, legacy candidates will be more likely than non-legacy candidates to secure the nomination. This is because legacy candidates will possess closer ties to local party actors, but also because the priorities in candidate selection may differ between local and national party actors. Although local actors may prioritize local connections (which legacy candidates frequently enjoy), party leaders at the national level may take a more diverse approach to candidate selection that serves broader goals for policy or party image—such as nominating more women, minorities, or policy experts to balance the party’s overall roster of personnel. The extent to which the priorities of the national party leadership are reflected in the attributes of the party’s personnel will depend on whether, and to what extent, the leadership exercises control over nominations.

When or if the leadership of a decentralized party attempts to centralize decisions in candidate selection, this effort may be met with resistance from local actors. The implication for dynastic politics is that politicians who want to perpetuate a family grip on politics in their local districts may oppose efforts by national party leaders to centralize control over nominations. Thus, whether the outcome of the candidate selection process results in a legacy candidate being chosen will ultimately depend not only on the relative utility that the party perceives it will get from nominating (or not nominating) a legacy candidate but also on the ability of party leaders to control the decision-making process.18

INSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN JAPAN AS A NATURAL EXPERIMENTThe two biggest challenges to comparative research on democratic dynasties are data availability and causal inference. The first is a challenge because historical biographical data on MPs and their relationships to other politicians are scarce for many democracies and may be unreliable in terms of accuracy in others. Finding and coding accurate data on candidates (not just elected MPs) is an even greater challenge. Where verified data on family ties are available, the complex nature of many relationships within dynasties can also make measurement and analysis a messy business.

For example, how do we treat two relatives with partially overlapping terms, or with several years between the final election of the predecessor and the first candidacy of the successor? How about a legacy candidate who runs in a different district from his or her predecessor? Or a pair of relatives where one person preceded the other in local political office, but the other was first to be elected into national office? And for legacy candidates with multiple generations of predecessors in politics, which relationship is the most important: the relationship to the most proximal member or the relationship to the founding member of the dynasty? All of these considerations make it extremely difficult to measure and analyze the true impact of dynastic ties across candidates within a single country, let alone across countries.

The second challenge to comparative research on dynasties, causal inference, arises because dynastic politics may be influenced by myriad country-specific, party-specific, or context-specific confounding variables that are difficult to measure and control in statistical analyses. Caution is warranted in interpreting any cross-sectional variation in a small-n comparative study. For example, it could be that multiple factors—including history, culture, population size, years of experience with democracy, or level of economic development—contribute to a country’s patterns in dynastic politics, and these factors may overshadow institutional effects. Similarly, dynastic politics within parties may vary by idiosyncratic differences related to ideology, personalities of leaders, time-specific events, size and age of the party, and so on. Political institutions are not randomly assigned to different countries—each arrives at its present situation through its own history and course of democratic development. Moreover, selection into a democratic dynasty is not random, much like selection into politics more generally (Dal Bó et al., 2017). This fact makes it difficult to separate the effect of dynastic ties from other traits when evaluating the downstream effects of dynastic politics. All of these factors also make it impossible to pinpoint the causal effects of the electoral system and candidate selection institutions through cross-sectional analyses.

The case of Japan presents a unique opportunity to gain analytical leverage over the effect of institutions on dynasties within a single democracy. From 1947 to 1993, members of the House of Representatives were elected using the single nontransferable vote (SNTV) electoral system in multimember districts (MMD). Under the SNTV system, each voter casts a single vote for a candidate in a district of magnitude M, and the top M candidates in the district are elected. In Japan, the average M was four seats. Any party that aimed to win a majority of seats in the legislature therefore needed to nominate more than one candidate in each district. Such intraparty competition resulted in elections that were “hyper-personalistic” (Shugart, 2001, p. 29), with candidates campaigning predominantly on the basis of their personal attributes or behavior rather than a commitment to their party label or its national policies.

This was particularly true for candidates from the dominant LDP, which almost always nominated multiple candidates in each district, often from competing internal factions within the party. Each candidate would thus work tirelessly to cultivate his or her own personal support base, known as a jiban in Japanese, to win elections. Candidates organized and maintained their jiban through personal support organizations called kōenkai, which were specific to each candidate and formally separate from the party organization.19

From its foundation in 1955 until 1993, the candidate selection process in the LDP was largely decentralized to local actors and subleaders. When an LDP candidate retired or died, his or her faction and the interest groups associated with the candidate—especially the kōenkai—often sought out family members of the outgoing candidate to run as successors. A candidate who immediately succeeds a family member in the same district after inheriting a jiban and its kōenkai organization can be defined as a hereditary candidate.20 Hereditary candidates constitute a special subset of legacy candidates, where the connection to the previous candidate is particularly close. The SNTV system meant that new candidates often had to challenge multiple incumbents in a district, so for factions and kōenkai members hoping to maintain control of a seat, a hereditary candidate with an inherited support base was the next best thing to having the previous incumbent run again. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, roughly a quarter of all LDP candidates were hereditary candidates who inherited their predecessors’ kōenkai and directly succeeded them into candidacy.

Candidate selection within the JSP and the more moderate Democratic Socialist Party (DSP) was also decentralized, but with greater influence exercised by the two parties’ main support networks of labor unions. In contrast, the Kōmeitō and the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) did not regularly nominate multiple candidates in a district, and both used a highly centralized candidate selection process. As a result, candidates from these parties could rely more heavily on their party labels in campaigning, and leaders had fewer incentives to seek out legacy candidates as successors. Indeed, neither the Kōmeitō nor the JCP exhibited anything near the same patterns in dynastic candidate selection as the larger, decentralized parties.

The rising trend in hereditary succession within the LDP might have been expected to continue well into the 1990s and 2000s. However, a series of corruption scandals and voter dissatisfaction with long-term LDP dominance, money in politics, and the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy led to several major party defections prior to the 1993 House of Representatives election. Many in the political and academic worlds saw the SNTV system as a key institutional cause of the problems plaguing the country. The end of the Cold War also deflated the importance of the LDP as the country’s political defense against communism and opened the way for new parties to enter the electoral arena. As a result of the election, the LDP narrowly lost its majority but remained the largest party. Eight other parties (excluding the JCP) formed a coalition government, which made electoral reform of the House of Representatives its top priority.

Reformers debated several variations on a mixed-member majoritarian (MMM) system (Shugart and Wattenberg, 2001) that would combine two parallel tiers of electoral competition: one a British-style first-past-the-post (FPTP) system in single-member districts (SMDs), the other a closed-list proportional representation (PR) system in regional MMDs. The MMM system that was ultimately adopted in 1994 and went into effect in 1996 was a compromise between reformers who hoped to create Westminster-style politics in Japan—party-centered election campaigns, with two strong, cohesive parties that alternate regularly in government—and smaller parties whose leaders knew that a pure FPTP system would spell their certain demise (Otake, 1996; Kawato, 2000).

The electoral reform eliminated intraparty competition, which dramatically reduced the candidate-centered nature of elections while simultaneously increasing the importance of party image and national policy platforms in campaigning and voting (e.g., Reed, Scheiner, and Thies, 2012; McElwain, 2012; Catalinac, 2016). In addition, the traditionally decentralized process for candidate selection in the LDP and other parties began to change. Since the 2000s, the LDP and other parties have experimented with a new method in candidate selection, open recruitment (kōbo), which expands the pool of potential candidates and places greater control in the hands of party leaders. This innovation was used most effectively by the DPJ, which replaced the JSP as the main opposition party in the postreform period. The process has been far from smooth in the LDP, with a key factor in the resistance to change being the continued desire among members of existing dynasties to continue their family business in politics. Nevertheless, since the first election under the new electoral system in 1996, and especially after reforms to the candidate selection process in the mid-2000s, the proportion of legacy candidates and MPs has begun to decrease. In the 2012 general election, the share of legacy candidates in the LDP dropped below 30 percent for the first time since 1972.

Meanwhile, the adoption of the new MMM electoral system has coincided with an increase in the percentage of legacy MPs appointed to the cabinet. Shortly after the electoral reform was adopted in 1994, the LDP regained control of government and ruled in coalition until 2009—when it was swept out of office by the DPJ’s landslide victory in that election. The LDP’s second period out of government ended with a reciprocal landslide victory over the DPJ in the 2012 election. Although the proportion of legacy MPs in the LDP has been decreasing steadily since the first election under MMM in 1996, the proportion of legacy MPs appointed to LDP cabinets has increased, to roughly 60 percent of cabinet ministers, on average, in recent cabinets. Moreover, seven of the ten prime ministers to have served since 1996—Hashimoto Ryūtarō, Obuchi Keizō, Koizumi Junichirō, Abe Shinzō, Fukuda Yasuo, Asō Tarō, and Hatoyama Yukio—have been members of powerful dynasties.

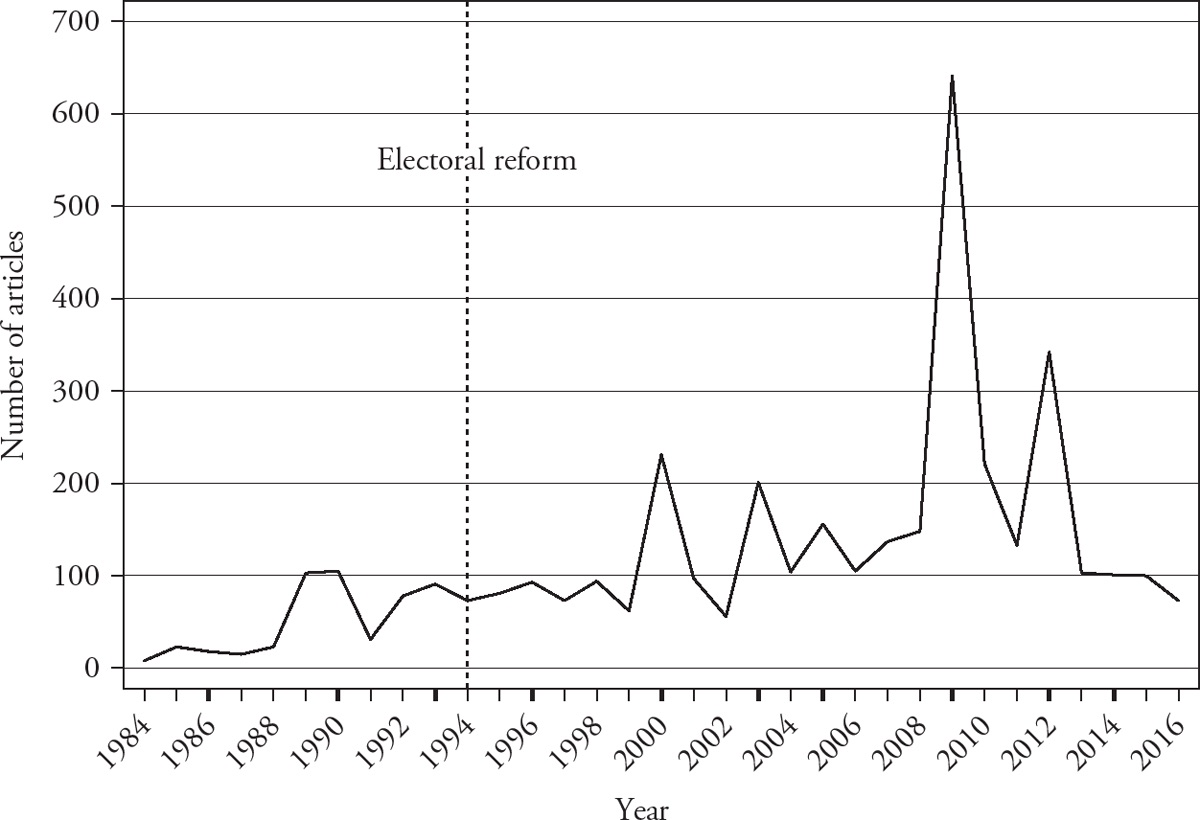

What has been the true impact of Japan’s institutional reforms on the importance of the inherited incumbency advantage and the practice of dynastic politics in candidate selection? And why has there been a decrease in new LDP legacy candidates since reform but an increase in their membership in cabinet? The electoral reform and subsequent party reforms in Japan might be considered a “natural experiment” of institutional change in an otherwise constant environment, which helps to resolve some of the challenges to causal inference that pose a barrier to comparative research on dynasties. Nothing about the reforms drastically changed Japanese history, culture, or other country-level variables that might affect the supply of legacy candidates. Moreover, the 1994 electoral reform was not directly motivated by the problem of dynasties,21 and references to dynastic politics did not noticeably appear in the media until several years after reform (Figure 1.2), in large part due to the prevalence of legacy MPs in the cabinet. Beginning in 2000, there were small upswings in coverage during election years for the House of Representatives, culminating in a huge spike in coverage around the time of the 2009 election, when the DPJ made an issue out of dynastic politics to attack the LDP. But by that time, the LDP had already changed its recruitment behavior in important ways, as this book documents.

In terms of dynastic politics, the electoral reform can therefore be treated analytically as an exogenous shock to the system, and we can apply rational choice theory to make predictions about how Japan’s new institutions should begin to structure behavior in new and different ways. In contrast, the party reforms to candidate selection within the LDP and DPJ can be considered endogenous responses to the new electoral environment. The case of Japan thus illuminates the dynamic and piecemeal nature of party responses to institutional change over time. When electoral systems and candidate selection procedures undergo institutional reforms, how, and to what extent, do voters, candidates, and party leaders respond to the new incentive structure? How many elections does it take for reforms to bear fruit? How do incumbents respond to new incentives, in contrast to newly recruited candidates? And how do incumbents and party leaders solve differences when new institutional rules put their priorities at odds—for example, when a retiring incumbent wants his or her child to take over as the next candidate, but party leaders prefer a non-legacy replacement?

The postreform MMM system also creates an opportunity to observe how parties’ candidate selection strategies differ across electoral system contexts (in Japan’s case, FPTP versus closed-list PR), even within the same country and election year. This type of “controlled comparison” using mixed-member systems has previously been used to shed light on parties’ nomination strategies with regard to women and minorities (e.g., Kostadinova, 2007; Moser and Scheiner, 2012; Manow, 2015) and can similarly help to rule out alternative country-level or time-specific explanations for dynastic politics across electoral institutions in Japan.

Finally, the concept of a jiban in Japanese electoral politics, and the prevalence of direct hereditary succession within the LDP, help to alleviate some of the methodological difficulties in measuring the electoral advantages enjoyed by legacy candidates. For example, direct hereditary succession removes the complexities of concurrent service by two members of the same family, or time gaps between predecessors and successors. The fact that some jiban are inherited by a non-kin successor, such as a political secretary, also provides an opportunity to assess how much of the inherited incumbency advantage can be attributed to family ties versus other types of ties, and how much of the inherited incumbency advantage can be attributed to name recognition versus simply the kōenkai organization and resources.

So What? The Consequences of Dynastic Politics

A separate question to “Why dynasties?” is whether dynastic politics actually generate any major consequences for the functioning of democracy in a country like Japan. In other words, so what? Do legacy candidates represent the most qualified among all potential candidates, or is the structure of the democratic system in places like Japan biased in favor of those privileged by birth with better connections or simply a more recognizable name? What are the potential problems arising from dynastic politics for the functioning of democracy, including the quality of representation and accountability?

Electoral systems and candidate selection methods are fundamental links in the chain of delegation and accountability that constitutes the core relationship between voters and their political agents in modern representative democracies (Strøm, 2000). The quality of representation can depend on who is elected and how responsive they are to the electorate’s interests. In most democracies, parties shape the nature of representation by determining whom among potential candidates the voters will evaluate at election time. In general, candidates and elected representatives chosen through these processes can be thought of as either “standing for” their constituents (descriptive representation) or “acting for” their constituents (substantive representation) through legislation or articulation of positions that serve the interests of those who (s)elect them (Pitkin, 1967). In the case of dynasties, it would be unsurprising that a legacy candidate, much like any elite politician, does not descriptively represent the electorate—most come from very privileged backgrounds and a narrow range of occupations. It is not obvious, however, that a legacy MP would do objectively worse at representing his or her constituents in the “acting for” capacity. Whether dynasties have positive or negative effects for the functioning of democracy is an open question in the existing literature.

NEGATIVE EFFECTS?One might argue that democratic dynasties are simply a benign fact of political life. Just as the offspring of doctors, lawyers, business owners, and even academics may want to follow in their parents’ footsteps, why should we be surprised or concerned if similar levels of occupational path dependence exist in politics as well? For a start, evidence from the United States suggests that occupational path dependence is significantly higher in politics than in other occupations, controlling for the prevalence of individuals in those occupations (Blau and Duncan, 1967; Laband and Lentz, 1983, 1985; Dal Bó, Dal Bó, and Snyder, 2009). This suggests that families might derive higher value from maintaining their status in the political elite than maintaining other occupational traditions. More generally, the prevalence of dynasties in a democracy may be symptomatic of the democratic process being “captured” by a small cadre of elites and a potential narrowing of the interests and voices being represented. Public opinion surveys in Japan routinely report that voters do not like the idea of dynasties in the abstract, even as individual legacy candidates continue to get elected to the Diet.

Dynastic politics might also lower the quality of representation. For example, if there is any regression to the mean with regard to political quality within a family, we should not expect legacy candidates to be as high in quality as their predecessors. Yet the inherited incumbency advantage enjoyed by legacy candidates may insulate them from competition or deter the entry of other, possibly more qualified, candidates. Once in office, electorally insulated legacy MPs might shirk their responsibilities and do a poor job representing their constituents. Much like how female candidates in the United States must outperform their male counterparts to overcome higher barriers to entry (Anzia and Berry, 2011), non-legacy candidates who run against legacy candidates might need to be of higher quality and exhibit higher legislative performance if elected. This means that when compared to non-legacy candidates, legacy candidates might paradoxically be of lower quality from the perspective of citizens seeking effective representation, even if they are of higher quality from the perspective of party actors in terms of electoral strength.

There is some evidence to support these concerns. For example, voters’ perceptions of political representation in India are much lower in areas represented by parties with dynastic leaders (Chhibber, 2013, p. 290). Similarly, members of dynasties in local Italian politics tend to have lower levels of education—a potential marker of quality—than nondynastic local politicians (Geys, 2017). Journalistic accounts in Japan frequently claim that legacy MPs are poor leaders and lack innovative policy ideas because of their sheltered, privileged backgrounds (e.g., Yazaki, 2010). Legacy MPs seem to enjoy an advantage when it comes to reaching the highest positions of power; yet at the same time, they may be less qualified to handle the difficult policy issues facing them once in office. Apart from Koizumi and Abe (in his second stint as prime minister after 2012), each of the recent legacy prime ministers in Japan failed to adequately confront political problems before stepping down within a year. This has resulted in a great deal of criticism of dynastic politics by the media, scholars, and opposition parties. Dynasties have been condemned as one of the factors contributing to political stagnation and public dissatisfaction with democracy.

Hideo Otake (1996, p. 277) notes that many legacy candidates in Japan had little serious interest in politics when they were pulled into candidacy by the kōenkai of their predecessors:

Their desire to be politicians had never been strong. Compared to Diet members who clawed their way up to national politics from the local level, these [legacy] Diet members did not see much point in becoming Diet members. Many inherited large fortunes and could afford comfortable living without working as Diet members. They shared an “I can always quit” easy-going attitude.

This “I can always quit” attitude may lead to poor outcomes when it comes to effective policymaking and representation. In 2009, DPJ party leader Okada Katsuya argued that the overabundance of dynasties in Japan “weakens the vitality of politics. Political parties need to recruit candidates from a wider field if they are to select the individuals most suited for the job.”22

Similar critiques of dynasties are made in the popular presses of the United States, Ireland, Italy, and elsewhere. For example, when Jeb Bush ran for the Republican nomination for president of the United States in 2016, the failures of his brother George W. Bush were regularly pointed to as reason enough to avoid putting another Bush in the White House. Jeb at first seemed to eschew association with his family name by using the simple slogan “Jeb!” before ultimately embracing his family legacy when his poll numbers floundered. On the Democratic side, former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley criticized Bush, as well as his own party’s front-runner, Hillary Clinton, by stating that the presidency “is not some crown to be passed between two families . . . new perspective and new leadership is needed.”23

In Ireland, W. T. Cosgrave and his son, Liam, were the first father-son pair to have both served as prime minister (Taoiseach). But the third generation of the Cosgrave line, Liam T. Cosgrave, fell rapidly from grace in 2003 after illegally failing to disclose political donations (Fallon, 2011). Renzo Bossi, the son of Lega Nord party leader Umberto Bossi, was thought to have a promising future career in Italian politics until it was discovered that he had been embezzling party funds and possessed a fake degree from a university in Albania that he had never once attended; he was forced to resign from his local seat in the Regional Council of Lombardy.24 David N. Laband and Bernard F. Lentz (1985, p. 402) equate legacy MPs who do a poor job in office to students who enter college on a parental “free ride,” only to flunk out after partying too much.

Legacy candidates might also pose problems for their parties if their personal electoral advantages allow them to buck the party line with greater impunity. The “I can always quit” mentality could apply not only to participation in politics but also to membership in the party. When legacy candidates have outside electoral options in other parties or as independents, it may become harder for party leaders to maintain discipline and party unity. Moreover, a potential legacy candidate who is denied the party nomination can create an electoral headache for the party if he or she runs against the party’s preferred candidate. There is thus a risk that parties might become captive to legacy candidates whose personal qualifications and policy priorities are at odds with the interests of the party as a whole. Of course, this risk applies with regard to any candidate with a strong personal vote; however, unlike non-legacy candidates with a strong personal vote, legacy candidates might be able to free ride on the reputations of their predecessors, reducing the connection between their own personal quality and their personal vote.

POSITIVE EFFECTS?Critics of dynastic politics often overlook the potential positive effects of dynasties on democracy. For example, electing a legacy candidate may bring continuity in the quality or style of representation for voters in a district, much in the same way as reelecting an incumbent. In considering members of dynasties versus “amateurs” in the US Congress, Glenn R. Parker (1996, p. 88) argues that members of dynasties may be beneficial to the functioning of the legislature, since “family members who have served in Congress can act in a tutorial capacity: knowledge is transmitted about the legislative processes (e.g., logrolling) and norms in the legislature (e.g., universalism).” Legacy candidates may be comparatively more comfortable and familiar with the policymaking process and able to commence political life with minimal training or socialization. To put a different spin on the previous analogy to college students, the experiences of non-legacy candidates and legacy candidates might instead be compared to first-generation college students (i.e., students whose parents did not go to university) and students whose families have a history of sending their children to university. First-generation college students tend to underperform relative to other students, at least initially, even controlling for IQ and secondary school grades (Terenzini et al., 1996).

The electoral advantages that legacy politicians possess may also translate into downstream distributive advantages for their districts. Legislator efforts to bring distributive benefits (commonly known as “pork”) to their constituencies tend to be lower where party identification among voters is stronger (Keefer and Khemani, 2009). In other words, legacy candidates elected on their personal reputation might be more motivated to provide benefits, or other forms of active representation, to their districts than politicians who owe their election to their party label alone. In addition, if legacy candidates tend to enjoy more election victories, their seniority status in their parties may help them to obtain important committee and cabinet positions with influence over distributive policy decisions—although this might not always result in better economic outcomes for their districts if the resources are directed only to favored support groups (Asako et al., 2015).

Anticipation of bequeathing one’s political resources to a family member in the future may also affect the behavior of incumbents. For example, it has frequently been hypothesized that incumbents in their final term may be more prone to shirking, or worse yet, personal rent-seeking behavior, since they no longer have to concern themselves with the accountability mechanism of reelection (for a review, see Fearon, 1999). Such concerns have sparked a large amount of research on the effect of term limits on incumbent behavior, with potential impacts on everything from legislative responsiveness to fiscal policy outcomes and political malfeasance (e.g., Besley and Case, 1995; Carey, 1996; Alt, Bueno de Mesquita, and Rose, 2011; Ferraz and Finan, 2011). Incumbents who expect their offspring to succeed them in office may have a longer time horizon to consider, and thus a greater incentive to maintain a positive reputation for their successors to inherit (e.g., Olson, 1993; Besley and Reynal-Querol, 2017). That said, strong parties with control over individual members’ behavior and a concern for the party’s reputation could achieve similar outcomes.

Finally, dynastic candidate selection might sometimes result in positive effects for gender representation, as the inherited incumbency advantage may help female candidates overcome informational inequalities or gender biases among party leaders or voters (Jalalzai, 2013; Folke, Rickne, and Smith, 2017). Dynastic succession may be one of the few ways for female candidates to break into politics in a system where women are generally disadvantaged electorally. Indeed, many female politicians in the United States and elsewhere first entered politics when their husbands died in office, a process sometimes referred to as a “widow’s succession” (Kincaid, 1978). At the same time, the institutional structures that contribute to dynastic politics are also likely to be impediments to greater gender representation—in other words, although women may fare best as legacy candidates, doing away with the institutions that encourage dynastic candidate selection would likely help level the playing field for more women to get elected without dynastic ties.

Road Map of the Book

The book proceeds as follows: The first part of Chapter 2 puts the case of Japan into comparative context with an overview of the empirical record across time, countries, and parties. This examination relies on an original panel dataset of the family ties of elected legislators (MPs) in twelve advanced industrialized democracies: the Dynasties in Democracies Dataset. The dataset covers the following countries and time periods: Australia (1901–2013), Canada (1867–2015), Finland (1907–2011), (West) Germany (1949–2013), Ireland (1918–2016), Israel (1949–2015), Italy (1946–2013), Japan (1947–2014), New Zealand (1853–2014), Norway (1945–2013), Switzerland (1848–2011), and the United States (1788–2016). The sources for these MP-level data vary by country, with most based on official biographies published by parliamentary libraries, and others based on careful archival research of additional biographies and newspaper reports.

The second part of Chapter 2 provides a descriptive account of the empirical record in Japan. The dataset used here, and in the remainder of the analyses for Japan, is the Japanese House of Representatives Elections Dataset (JHRED). This panel dataset includes all candidates who ran in any general election or by-election for the House of Representatives from 1947 to 2014. The dataset spans twenty-five general elections, seven of which occurred after electoral reform in 1994. It does not cover elections for the House of Councillors, the upper chamber of the Diet, although it does code whether a candidate previously served in that chamber, as well as family relations to members of that chamber.25 The House of Representatives is the larger and more important of the two chambers, with sole responsibility for the drafting and approval of the budget, the ratification of treaties, and the designation of the prime minister. In addition, although the House of Councillors has enacted minor reforms to its electoral system over time, the 1994 House of Representatives electoral reform has been the major institutional change affecting the evolution of Japanese politics in the past two decades. Throughout the book, the general term “MP” refers to members of the House of Representatives unless otherwise indicated. Details of both datasets can be found in Appendix B.

The empirical record illustrates several motivating patterns. First, even though democratic dynasties exist throughout the world, there is considerable variation across countries, parties, and time. Second, Japan stands out as one of the most dynastic countries among the comparative cases—with the level of dynastic politics initially growing over time, in stark contrast to the pattern in most other democracies. The high level of dynasticism is largely accounted for by candidates associated with the LDP. Legacy candidates in the LDP and other parties tend to be more successful than non-legacy candidates, yet the empirical record suggests that there are few differences between legacy candidates and non-legacy candidates in terms of personal characteristics, experience, education, or background—apart from their legacy ties—that might explain this greater electoral success.