In August of 2015, I was in Chicago meeting with several thousand fellow sociologists at our annual conference. That year, everyone was abuzz with statements made by Aziz Ansari (this was before he was “canceled,” the first time, for sexual misconduct) at the conference plenary, “Modern Romance: Dating, Mating, and Marriage.” I was more taken with a comment made by another panelist, Christian Rudder, cofounder and former president of OkCupid. Rudder joked, “If you think your matches are ugly, it’s probably because you’re ugly,” as he explained the mechanics of OkCupid’s matching and sorting algorithm. He stated that matches reflect a mathematically generated score that is a combination of several factors: attractiveness scores, how often users send and respond to messages, and how much traffic a particular person generates on the app. I began to wonder how these scores take for granted the social norms that underlie such sorting. In the simplest terms, algorithms are a set of rules, directives, or mathematic calculations. Online dating algorithms are simply programmed to predict or mimic expected behavior using data gathered about an existing user base. The hidden assumption is that these mathematically based systems can predict attraction and attractiveness, while eliminating, to some extent, user bias. Even if they can successfully predict these socially constructed concepts (which is debatable), should we trust artificially intelligent systems to pick whom we might see on intimacy platforms?1

Dating apps are said to mimic modern dating practices. Traditional, offline dating experiences were largely based in networks. Individuals met people in areas that they frequented in their neighborhoods, at the local bar, the grocery store, and so on. People also used to (and still do) date friends of friends. When speaking to some of my senior colleagues about this book, they always liked to remind me that there was more social pressure to stay together in the past. The fact that you had mutual friends in the same networks meant that you had more incentive to try to make it work. At first glance, a sorting algorithm might not seem like such a bad idea, especially when users are led to believe that their matches are curated based on a matchmaking questionnaire like the ones featured on OkCupid and eHarmony. While this is in part true, it may also be desirable to browse through the entire “universe” of users in an area.

Matching and sorting algorithms are designed, to an extent, to replicate these offline dating processes. The early days of Tinder provided an extra layer of “security” in that the user would be presented with matches that had some relation to people in their network by connecting to their Facebook account. The user is led to believe that location parameters can guide them toward either a more traditional experience (if the location settings are set to within 5 miles of where they are located) or toward a less traditional experience (if the user sets their location settings to within 250 miles). The offline courtship and dating game would not traditionally allow for a long-distance first introduction. In some ways, intimacy apps widen the universe of users with whom we have the opportunity to interact. But through other, more opaque processes, dating apps can limit and make decisions for users about would-be partners based on race and attractiveness before the user ever sees prospective partners. These factors restrict whom we would encounter in ways that are unnatural for some.

If your networks are racially and socioeconomically homogeneous (White, heteronormative, and wealthy), you might seek to replicate these parameters in the context of your online dating options. However, if you are hoping that your quest for the perfect match might include all the diversity of the human experience, you might be better off searching elsewhere because implicit in the attractiveness scores used to train algorithms are all of the social norms and beliefs about beauty and desire that society believes to be most admirable: peak feminine attractiveness is White, blonde, symmetrical, and thin. The pinnacle of masculine desirability is White, tall, and athletically toned with a chiseled jawline. In short, an algorithm might decide that you are too attractive (or not attractive enough) for a particular match before you or the person on the other end ever has a chance to awkwardly meet and decide for yourselves—especially if someone in the equation does not exist within the framing of normative beauty and desire.

The OkCupid founder’s “joke” actually revealed a harsh truth of the online dating industry. Their algorithms optimize bias and pre-sort potential matches based on your own physical features. Their decisions about whom you might be attracted to (and whom you may attract) are largely influenced by how you look, how attractive the algorithm deems you to be, and how often other highly attractive individuals have interacted with your profile. Of course, in the minds of those at online dating companies, they are doing you a favor by quickly eliminating those you might not find attractive (or whom you may not attract). Their ultimate truth, though, is that sending you too many “unattractive” matches may turn you away from their service, causing them to lose out on profit. The question then is, should they do this?

Though biologists debate the degree to which attraction is biological, social scientists commonly hold the perspective that what is considered attractive substantially differs from culture to culture, across continents. Attractiveness, beauty ideals, and the racialized and gendered norms that coexist alongside and shape these concepts shift over time. Moreover, we perform beauty, and the reception of that performance is audience specific. In the United States (and across the globe) racism further complicates beauty and attractiveness norms. Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins argues that the authority to define beauty norms and gender ideas is an instrument of racialized power.2 Gender scholar Judith Butler further informs that ideals about beauty and attractiveness are entangled with expectations about the performance of gender, masculinity and femininity.3

If these socially constructed racialized beliefs about attractiveness, femininity, and masculinity are so deeply entrenched in our society, how can the algorithms that govern our online intimacy experiences claim to avoid them? Or is it the case that they rely specifically on this human bias as a measure for sorting? How do algorithms perpetuate the ideas that undergird our learned beliefs about race, gender, and attractiveness? This book presents a deep exploration of these entangled ideas and concepts, centering on the larger question of how algorithms used by intimacy platforms impact the online dating experience of anyone who is not the archetypal White, male-presenting, straight guy.

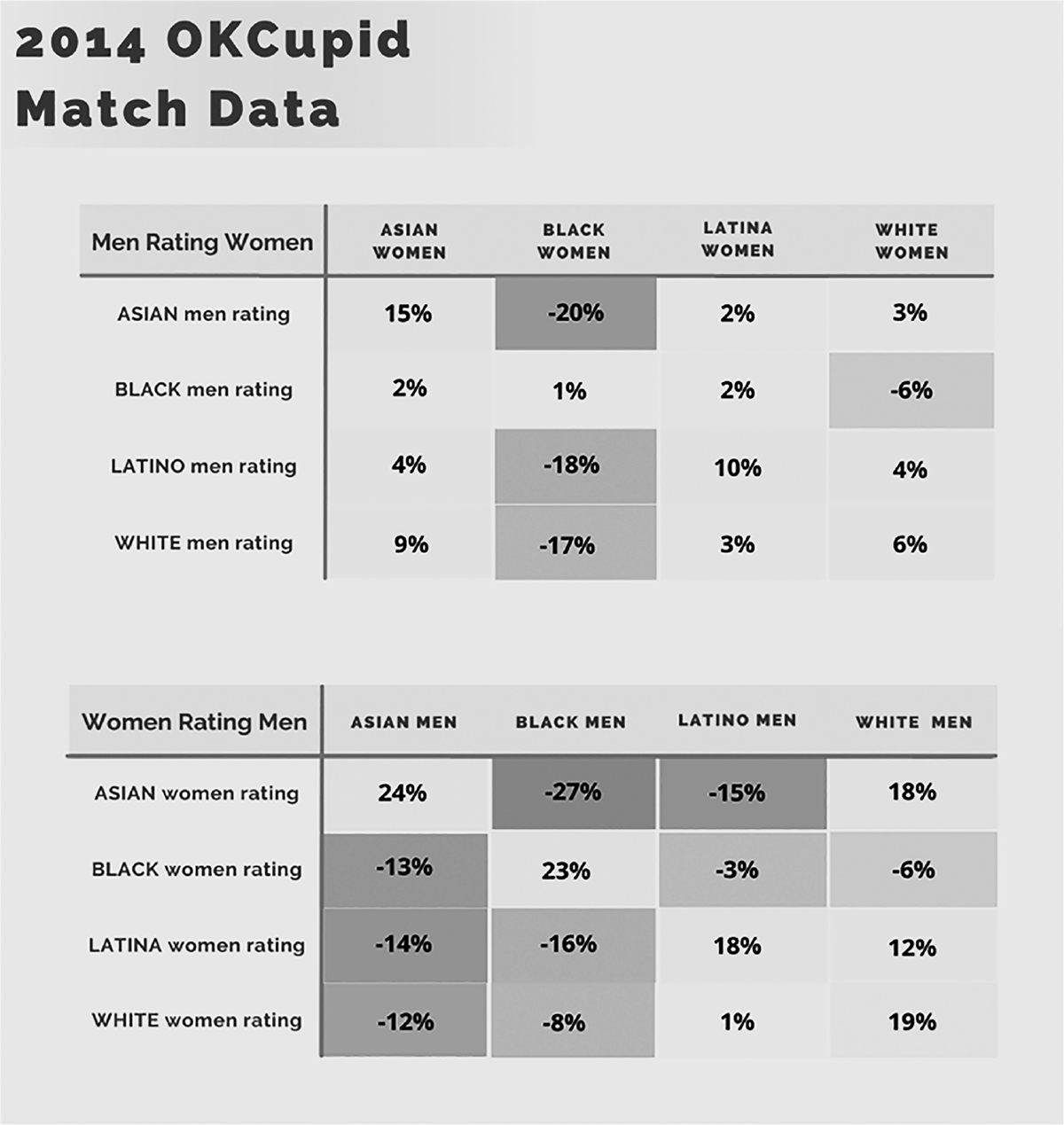

The problem, though, is that straight White dudes and White women are the users for whom the dating companies build their platforms, despite evidence that dating sites are increasingly used more by Black users and other folks of color than White daters.4 Designing for the normative user presents a problem for the rest of us whose experiences differ greatly.5 One very important difference is how White daters and daters of color experience race and racism while using dating platforms. Most White users of dating apps—whether gay, bisexual, pansexual, or straight—find it acceptable to express racial preference in a partner.6 In 2014, the most up-to-date statistics provided by OkCupid showed how people tend to select matches in accordance with racial preference. Figure I.1 shows that Black, Latina, and White women rate Asian men as 13, 14, and 12 percent less attractive than other men on the platform, respectively. Black men are rated as 27, 16, and 8 percent less attractive than other men by Asian, Latina, and White women, respectively. Asian women rate Asian men as 24 percent more attractive than other men, and Black women rate Black men as 23 percent more attractive than other men.7 These numbers demonstrate the sociological principle of homophily—the idea that like attracts like. We would expect members of one racial category to rate more highly the attractiveness of other members of that same racial category.

However, homophily does not account for such strong negative bias against members outside of one’s racial or ethnic group, suggesting that racial preference is not meaningless. The first graph indicates that Black women are rated as less attractive by members outside their racial group, while the same does not hold true for Asian and Latina women. This racially disparate effect is, in part, the result of racial tropes and racist stereotypes that position Black women as hypersexual and undesirable for long-term relationships.

While White people may feel that their racial preferences are neutral, harmless expressions of desire and compatibility, most people of color find these racialized choices to be overtly racist. This kind of racism has a name: sexual racism. Often concealed as private, meaningless personal preference,8 I define sexual racism as personal racialized reasoning in sexual, intimate, and/or romantic partner choice or interest. In broader societal context, sexual racism connotes a set of beliefs, practices, and behaviors at the intersection of what is considered acceptable racialized gendered performance. This theoretical framing is important for understanding how dating and intimacy platforms allow sexual racism to flourish because they rely on White normative standards of attraction, desirability, and gender aesthetics to program sorting and matching algorithms. At times, dating companies’ attractiveness ranking algorithms even seem to rely on the logics of eugenics: the closer one is to White ideal beauty aesthetics, the higher one’s attractiveness score. By concealing this process and underlying logic from users, the companies help perpetuate the belief that there is an unbiased normative standard for beauty and that any preferences we have are morally neutral and should remain unquestioned. Hence, dating platforms automate sexual racism and White supremacist beliefs about beauty and desirability by failing to disclose the use of racialized ranking and sorting systems and by allowing users to target and racially fetishize people of color.

I argue that we should hold online dating companies accountable for their part in automating and legitimizing sexual racism, transphobia, and violence against minoritized people. While online dating seems to be a benign digital tool used to pursue mating, dating, and society’s ultimate goal of marriage, sociologists understand that mating and marriage are opportunities for racialized social control (especially within the racial historical context of the United States). Put simply, the political overlaps with the personal in our choices about with whom we date, couple, and partner. Narratives of sexual racism help to define, structure, and justify racial distinctions in other arenas of power and structured social control.9

1. Kathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (New York: Broadway Books, 2016).

2. Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 2002).

3. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 2002).

4. Monica Anderson, Emily A. Vogels, and Erica Turner, “The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating,” Pew Research Center, February 6, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/06/the-virtues-and-downsides-of-online-dating/

5. Afsaneh Rigot, Design from the Margins: Centering the Most Marginalized and Impacted in Design Processes—from Ideation to Production, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, May 13, 2022. https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/design-margins

6. Denton Callander, Christy E. Newman, and Martin Holt, “Is Sexual Racism Really Racism? Distinguishing Attitudes Toward Sexual Racism and Generic Racism Among Gay and Bisexual Men,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 44, no. 7 (2015): 1991–2000; Jesús Gregorio Smith et al., “Is Sexual Racism Still Really Racism? Revisiting Callander et al. (2015) in the USA,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 51, no. 6 (2022): 3049–3062.

7. The original OkCupid website with this data has been taken down. The data are available at Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/Okcupid/comments/n1hdmm/okcupid_quickmatch_scores_based_on_race/

8. Sonu Bedi, Private Racism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

9. Celeste Vaughan Curington, Jennifer Hickes Lundquist, and Ken-Hou Lin, The Dating Divide: Race and Desire in the Era of Online Romance (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021); Collins, Black Feminist.