The world around us is changing at unprecedented speed. At this tipping point, our traditional concepts of society, meaningful employment, and the nation-state are challenged, and many understandably feel insecure or even threatened. A new model of responsive and responsible leadership is needed to allow us to address the challenges the world faces, from security to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, with long-term, action-oriented thinking and solidarity on both the national and global levels.1

These are the words of Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum (WEF or the Forum), calling for participation in the Forty-Seventh Annual Meeting in Davos, which took place January 17–20, 2017, under the theme “Responsive and Responsible Leadership.” This meeting attracted, among others, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres; the president of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping; the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Christine Lagarde; then US Secretary of State John Kerry; UK Prime Minister Theresa May; over one thousand CEOs of business corporations (among others, CEO of BP Bob Dudley and Google cofounder Sergey Brin); German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter; Colombian singer Shakira; and Queen Rania of Jordan. All in all, an estimated three thousand world leaders from politics, finance, business, and science attended the meeting.

The WEF has positioned itself as the prime meeting place for top world leaders and as the advocate of burning global issues. According to its world-view, the world is at stake, facing imminent and grave challenges that can be dealt with only by pragmatic and future-oriented actions and positive narratives. Only responsible leadership, courage, and commitment can counter issues such as financial crises, terrorism, environmental disasters, poverty, and social marginalization. The WEF sees itself as providing a critical response to this call. As expressed by Klaus Schwab, “The problem that we have is not globalization. The problem is a lack of global governance, a lack of means to address global issues.” In this narrative, the World Economic Forum is the equivalent of the symbolic figure Marianne in the French Revolution—in this case, on the global scene—leading the world to future victories. This self-perception, sense of responsibility, and view of what’s wrong with the world and how to tackle it go back to the early days of the organization. As long ago as the late 1980s, Schwab had said:

We who take charge should not leave the “taking care” to others. Today, taking care means recognizing the interdependence of all people and nations in the world; recognizing the interdependence of the economy and ecology; recognizing the fact that being successful creates special responsibilities towards the world community. The vision of the future is to integrate these two concepts: taking charge and taking care.2

Without a given mandate, the Forum has conferred a specific role on itself: “To create global partnerships among those who exercise the highest responsibilities in business, government and academia” in order to “improve the state of the world” (according to its motto). In the WEF’s own words, “The best tool to get this done in our complex world is effective, direct and personalized interaction.”3 Against the backdrop of what is perceived to be malfunctioning global governance institutions and stalled international policymaking, the WEF presents itself as offering an alternative global platform for engaging with global problems. It provides a forum for modernized, globalized, and alternative politics. Moreover, it invites world leaders to be part of forging new forms of influence, based not on the legal mandate of state or international institutions but on the exercise of discreet power.

Turning our attention to the WEF, we ask: What type of governance is the WEF aspiring to create? Looking more closely at the processes through which the WEF wields power and authority and the form of governance that is articulated, we also ask: How is global politics possible?

Toward the Summit

Every year in late January, the Forum holds its renowned Annual Meeting at the Swiss ski resort Davos, where invitees and funders flock to mull over the state of the world. In this snowy mountain town, some one thousand industry and finance leaders and two thousand leaders from some one hundred countries, from international and civil society organizations, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), labor and faith-based organizations, politics, and academia, present their views on the economy, their visions for the future and their arguments for the best solutions to tough problems.

During this week, Davos changes from a sleepy alpine town to a hub of influence, power, and prestige, addressing pressing global concerns. A wide array of values and priorities, and various ways of reaching defined goals, are articulated and discussed. Lines of convergence and divergence of community and exclusion are drawn as the WEF makes its presence felt. The Davos meeting, however, is not solely a gathering of the world’s business leaders, economists, and politicians; a smattering of celebrities also brings glitz and flocks of media people. It is a meeting with many facets: an exclusive elite summit, a glimmering cocktail party, and a marketplace. And the summit is the prime WEF event for which staff in Geneva plan all year.

For three consecutive years (2011–2013), we were there, in Davos. The meeting in 2011 was our first.

Davos, January 2011: In the Power Nexus

Having just arrived in the village, we venture out to explore the area. We had failed to obtain a formal invitation but have decided to crash the summit, to see the extent to which we can participate. This being 2011, the global economy and capitalism are at the top of the agenda, with the theme “Shared Norms for the New Reality.” The sense of urgency is still high after the financial crisis, and the event and the town are sprinkled with a certain frenzied activity and nervousness. But there is also a sense of possibility—the opening of new markets for innovation and profit, for global collaboration and mutual benefit.

The streets of Davos are filled with participants in elegant business suits and overcoats, easily identifiable by their badges and briefcases sporting the WEF logo. BMWs, Mercedes, and other pricey cars are conspicuously abundant, as are Western middle-aged businessmen. Banners with the WEF logo hang from buildings and hotel lobbies and are printed on café menus. Buses and houses also display ads for individual countries—India, Brazil, and Mexico among them. On a busy street corner, Canadian Mounties in their red serge pose in front of a stand serving free BeaverTails, a flaky pastry shaped like, yes, beaver tails.

Journalists are roaming the streets, camera equipment and microphones at hand. CNN, BBC, Reuters, and other conglomerates are well represented here and clearly visible by their logos. Now and then we run into a team of journalists who have managed to halt a celebrity or some more ordinary participant to obtain a brief interview. Not every journalist who volunteers to come is welcome, we later learn. Journalists must apply for permission several months ahead, and access is restricted to WEF trusted members of the press.

And then there are the regular visitors to Davos: skiers in their skiing pants, skis on shoulders, jostling with meeting participants, police, military, and maintenance staffs. Only the more economically solvent skiers can afford Davos during this week, when WEF participants and journalists are occupying all the rental apartments and hotel rooms, and prices soar for the few vacancies. The WEF has booked most hotels and apartments well ahead of time. The upside is that the slopes tend to be relatively empty. Nevertheless, some of the skiers appear to be irritated as they make their way through the crowded streets, the busy restaurants, and the fuss of having to navigate around the cordoned-off areas of the village.

As we make our way through the narrow streets, the sunshine sparkles on the snow, illuminating the slopes of the high mountains. The thermometer shows a brisk 14 degrees Fahrenheit, and the air is crisp and light at this altitude of 5,120 feet. We learn that the conference center occupies a large part of the town, now surrounded by high barbed-wire fences. Armed guards secure the gates, and anyone who approaches must present a meeting badge and registration papers.

As we approach, we spot the entrance gates for the meeting compound, with a small shack erected for the occasion. Posted before the two gates are four guards in gray uniforms, automatic weapons on their shoulders. Five more guards are posted on the inside of the gates. It looks like Checkpoint Charlie. We observe guards from the Swiss special police force standing on the roof of the Hotel Belvedere, dressed in camouflage uniforms, heavily equipped and wearing masks. CCTV cameras are posted around the entrance gates and stare at us from above. Swiss Army helicopters hover, and occasionally F/A 18 Hornets, a type of combat jet, intercept their trajectories, drawing white lines across the blue sky. The soundscape created by the air security embeds the small town with a constant pattering noise. After the meeting, we learn that up to five thousand Swiss soldiers took part in the security operation, Alpa Eco Undici, which was staged for the WEF that year.

The guards ask us for our badges, but we have none. Unaware of the entry restrictions, we had arranged for a first meeting with a Scandinavian participant inside the meeting area. Olafur Gunnlaugson, from one of the larger corporate foundations in Scandinavia, has agreed to meet us at Pizzeria Daiano inside the compound, we explain.4 It’s important that we get inside. After a few minutes of arguing, pleading, and looking desperate, the guard decides to let us in, but only as far as the pizzeria, and he never lets us out of his sight until we enter.

Over lunch, Mr. Gunnlaugson, a gracious-mannered man in his fifties, says: “If you are not here, you do not exist”—in other words, every actor or organization with some ambition in the global business arena is here. “The networking is central, but seminars are also very stimulating,” he goes on. “The meeting is a melting pot of finance, politics, research, an institution that works. Participating in the Davos summit, one can, in the long run, contribute to improving the world. It’s business with social engagement,” he asserts.

After lunch, we continue our tour outside the premises, following the wired fence. This walk takes us a good hour, our high-heeled boots get wet and cold from the exercise, and our mood drops. There are a couple of more gateways but nowhere the general public can enter. Having tried our luck with the guards at every entranceway, we venture with disappointment into the town center.

The following day, we make our way toward Café Schneider, where we have arranged for a lunch meeting with Bill Gladstone, president of a CEO-led global association of some two hundred companies dealing with business and sustainable development. Café Schneider is located on the main street of Davos and has been temporarily turned into an important WEF hub. It is housed in a classical Swiss alpine building, with a steeply pitched roof and wooden decor. Gladstone’s assistant has reserved a table for us, and the headwaiter directs us to it. The interior of the café reflects a mixture of rustic mountain cabin and smart business style. The white linen cloths and napkins and a tempting menu contribute to our appetite. The snow melts from customers’ coats and boots, the smell mixing with the aromas of food cooking in the kitchen.

Mr. Gladstone, a neatly dressed and good-natured man in his sixties, appears ten minutes later. We engage in a long conversation about why it is that someone like him decides to come to Davos, what his organization aims to get out of the meeting, what goes on here, and what, if any, the implications of meetings held here might be. He freely tells us about his motivation. “Nobody is in charge of global problems,” he starts out. “Only business has the resources to deal with the serious ones.” In his view, governments now understand that they cannot deal with them alone. Cooperation is necessary, not least when it comes to the issue of sustainable development. He goes on to talk about the urgency of the situation in the world, about attempts at regulating carbon emissions, climate agreements, and the like, exemplifying with concrete issues and events. When he has finished painting the global picture, he asserts:

The World Economic Forum is a platform. It relies on a multistakeholder model, on the idea of bringing diverse interests together around the same table. The World Economic Forum, however, is not a locus for decision making; it is an idea distributor. The WEF doesn’t do any advocacy in its own name. Rather, it provides a venue for strategic partners to pursue issues and make decisions.

A little later in the conversation, he adds, “We [the organization] are here, we participate, provide our points of view. We are the leading voice of the global capital.”

During our conversation, several well-known people come to greet Gladstone, among them the executive director of the UN Global Compact.

After Gladstone leaves, we remain seated, and note that we are not being asked to leave. Quite the contrary: the waiters pay us continuous attention and do their best to make us comfortable. It appears that we are believed to be of some importance, and this proves to be the case over the following days; the table is kept for us over lunchtime, without our having made the slightest move toward making a reservation. Gladstone’s prestige and that of his network have undeservingly rubbed off on us. And for the first time, we feel what it is to be included in the WEF network and how the allure of it works. It rubs off on people who, for various reasons, aspire to get into the new global nobility.

This book builds on four years of our on-and-off ethnographic fieldwork on the WEF. Since that meeting in 2011, we have followed the activities of the organization by attending, or attempting to attend, meetings, seminars, and workshops in various locations across the world. When we have not been given permission to attend, we have circulated the peripheries of meeting compounds, talking to participants, WEF staff, skiers, drivers, members of the Occupy Movement, bartenders, journalists, and others on the margins of events. Whenever we were granted access, we participated in meetings and other events organized by the WEF, chatted in lobby areas, attended cocktail parties, and hung around hotel bars. We have also had conversations and interviews with staff members at the headquarters in Cologny outside Geneva, with funders and participants in meetings, and with others associated with the organization.

Over time, our inroads and positions in the field have given us a rich and varied understanding of the organization. We aim to bring these insights and experiences to bear on a story about the WEF as an organization, articulating many central dimensions of the contemporary world and the challenges associated with global governance. At the core, we want to convey how the WEF works to push its ideas by way of seduction and what we call discretionary governance at the transnational level—the exercise of a discreet form of power and control according to the judgment of the Forum and its members, in ways that escape established democratic controls. We aim to demonstrate how the Forum, together with its funders and invitees, contribute to shaping a fragile political mandate with a significant global sway. Through the strategic use of seductive communicative actions, the WEF and its leaders endeavor to shape the interests and priorities of others, attracting and enticing them into engaging with political issues defined by the Forum and running with them. In the broad sense, seduction entails drawing people in and holding them in one’s thrall. It involves radiating some quality that attracts others and stirs their emotions and influences their thoughts in ways desirable to the seducer. Thus seduction is intimately tied up with discretionary governance—the practice of a discreet and subtle form of soft power that works more effectively than coercion.

Governing the World

The contemporary world is characterized by unprecedented globalization. Various parts of the world are now interconnected by way of increased trade and economic activity, faster and thicker communication networks, and intensified points of engagement and tension among cultural groups. Even if globalization occurred long before the term was coined, we are now living in a world where the infrastructure of nation-states and international connections are giving way to a novel geopolitical structure characterized by global and transnational connectivity. Since the end of the Cold War, the driving forces of societal change, of economic, political, and cultural dynamics, have been transnational rather than international.5 In some instances, we are even experiencing the implications of supranational driving forces, challenging the nation-state as a template for societal coordination and order.6

The global political arena is fraught with challenges and contradictions. It is also ripe with opportunities to make a difference and improve the state of the world. As many scholars have noted, globalization is not a unidirectional process but an open-ended, contested, and ambiguous one. People and societies are affected differently, to different degrees and at different speeds. Moreover, some groups of people and some organizations are in more privileged positions not only to harvest the fruits of globalization but also to shape its process, direction, intensity, and speed.

At this time, corporations are among the foremost drivers, setting the parameters for social development. Likewise, organizations sponsored by corporate money, such as think tanks, foundations, and advocacy groups that are able to coordinate corporate interest around particular topics, are gaining leverage on the global scene.7 In this context, the Forum is a child of its time, reflecting the standing of the transnational corporation and the leverage that can be gained from attracting corporate funding and organizing corporate interest into a larger whole. As a nonprofit think tank with global reach, the WEF builds on the exclusive funding of large transnational corporations to shape the direction of globalization with one overarching ambition: to “improve the world,” as the slogan has it.

Globalization has not only accentuated the weaknesses of the geopolitical infrastructure built on the nation-state template, but brought to the fore significant challenges with regard to governance. Nation-state governments are under heavy pressure to regulate and oversee the operations of transnational corporations. Despite international law and conventions, corporations often find loopholes and resort to forum non conveniens (that is, relying on courts not to take jurisdiction due to lack of an appropriate forum) to avoid legal sanctions. Voluntary codes and standards may compensate to some extent for the lack of binding transnational legal structures, but they rely on the goodwill of the parties to have effect. Transnational insurgencies and terrorist attacks are laying bare the fractions and tensions brought about by the disjunctures of globalization, for transnational identity politics are not only uniting but also dividing groups of people along new lines that seldom correspond to nation-state orders and regulatory structures. Recent transnational migration waves, propelled by war and conflict, not only alert us to the fickle nature of the global order but also point to the shadow side of globalization and the incapacity of existing structures to govern key policy areas effectively. The Brexit vote, the right-wing populist movements in Hungary and Poland, and the neoconservative tailwind in the United States are prime examples.

The WEF itself is a response to the governance gaps laid bare by intensified globalization. The challenges of the nation-state to effectively regulate transnational trade, the unprecedented global risks associated with climate change, the political insurgencies of recent decades, and the incapacity of the post–World War II global organizational architecture to move forward in the direction of change have made their imprints on its organizational structure and way of functioning.

Established in 1971 by Klaus Schwab, a professor of business policy at the University of Geneva, as the European Management Forum (EMF), based on a nonprofit foundation based in Geneva, Switzerland, the organization aims to provide an alternative to established international organizations, such as the United Nations (UN) and its many suborganizations. In this context, the UN is perceived as being too inert, too slow to set change into motion, and too exclusive in its membership, which rests on nation-states and fails to include the voices of corporations and other organized communities. In addition, the establishment of WEF has a personal side to it. As Chairman Schwab explained to us, the birth of the WEF is an outgrowth of his childhood war experience and his desire to help make the world a better place in which to live. Born in Ravensburg, Germany, in 1938, Schwab experienced World War II, and the human suffering made a strong imprint on him. Trained as an engineer and an economist, he founded the Forum with the aspiration that it would become a platform for public and private cooperation, a driver for reconciliation, and a catalyst for multistakeholder collaboration and initiatives for achieving long-term growth and prosperity.

As Schwab expressed it, “The World Economic Forum is “a response to a need. We were not mandated by anybody. We created . . . a response to a clear need in the international governance system.”8 The organization was thus created to offer a platform for leaders of government, business, and civil society to join forces in making the world a better place. Each January, the organization draws business, political, and civil society leaders from Europe and beyond to Davos for the Annual Meeting. What is described as the collaborative and collegial “spirit of Davos” has thus grown out of four decades of meetings of carefully selected leaders and aspirants.

Organizing for Global Aspirations

In the beginning, WEF meetings were focused primarily on European matters and how European business could catch up with US management practices. In fact, the WEF was initially established under the patronage of the European Commission (EC), and European industrial associations that had a strong interest in strengthening the competitiveness of European business. Soon after, however, the WEF cut loose from EC and turned its focus increasingly toward global issues.

The stakeholder management approach, which over time became a signature model for the WEF, was developed during these early years. This model bases corporate success on managers, taking account of all interests—not merely shareholders, clients, and customers of the corporation, but also employees of the corporation, trade unions, and the communities within which it operates, including government. Schwab outlined the approach in 1971, the same year as the Forum was established, in his book, Moderne Unternehmensführung im Maschinenbau (Modern Enterprise Management in Mechanical Engineering).9 In it, he argued that the management of a modern enterprise must serve all stakeholders (die Interessenten), “acting as their trustee charged with achieving the long-term sustained growth and prosperity of the company.”10 In 1973, participants at the Annual Meeting codified the approach into a code of ethics, termed “The Davos Manifesto.” The first point in the manifesto states that the purpose of professional management is to serve clients, shareholders, workers, and employees, as well as societies, and to harmonize the different interests of the stakeholders.11 The enterprise shall thus serve not only the shareholders and clients but also employees and society at large. This is to be ensured by securing long-term profit for the enterprise, stated in the manifesto’s last point:

The management can achieve the above objectives through the economic enterprise for which it is responsible. For this reason, it is important to ensure the long-term existence of the enterprise. The long-term existence cannot be ensured without sufficient profitability. Thus, profitability is the necessary means to enable the management to serve its clients, shareholders, employees and society.12

Over time, the move from an emphasis on managers to the contemporary emphasis on multistakeholders led to a refinement of the model. The multi-stakeholder model builds on visions of aligning key priorities and values from various actors. A basic assumption underlying this model therefore is that the values of economic growth and social and environmental sustainability can and must be aligned and balanced in order to reach the universal goal of survival—or at least the goal of improving the state of the world.13

Schwab’s vision for what would become the WEF grew steadily. Events in 1973—the collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate mechanism and the Arab–Israeli War—saw the Annual Meeting expand its focus from management to economic and social issues. Political leaders were invited to Davos for the first time in January 1974. Two years later, the organization introduced a system of funding by incorporating what it referred to as the one thousand leading companies of the world as members. At roughly the same time, the EMF was claimed to be the first NGO to initiate a partnership with China’s economic development commissions, spurring economic reform policies in China. Regional meetings around the globe were added to the year’s activities. The publication of the first Global Competitiveness Report in 1979 saw the organization expand and aspire to become a knowledge hub.14

A significant turning point for the Forum was 1987, which marked the transformation of the EMF into the WEF. Now the organization sought to broaden its vision to include the provision of a platform for dialogue for world leaders, not merely European leaders. In its newly established journal, World Link, Schwab described how the WEF identified thirty-five thousand leaders across the world. These leaders went under the label “33333” and were drawn into the “World Link system,” a communicative network through which Forum leaders wanted to educate and prepare leaders for global action.15 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting milestones during this time include the Davos Declaration, signed in 1988 by Greece and Turkey, which saw the two countries turn back from the brink of war. In 1989, North and South Korea held their first ministerial-level meetings in Davos. At the same meeting, East German prime minister Hans Modrow and German chancellor Helmut Kohl met to discuss German reunification. In 1992, South African president F. W. de Klerk met Nelson Mandela and Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi at the Annual Meeting—their first joint appearance outside South Africa and a milestone in the country’s political transition.16

The alignment of economic, social, and political interests has thus been part of the WEF since the first meeting in 1971. In the 2000s, the WEF launched the Davos Equation in order to emphasize the bond between the economic and social worlds:

We live in a world which is uncertain and fragile. At the Annual Meeting in Davos, global leaders from all walks of life will confront one basic fact: We will not have strong sustained economic growth across the world unless we have security, but we will not have security in unstable parts of the world without the prospect of prosperity. To have both security and prosperity, we must have peace. This is the Davos Equation: security plus prosperity equals peace.17

The equation aims to capture the idea of a balanced and neutral solution to global problems of all kinds: peace, health, education, and so forth. The very notion of “equation” implies symmetry or balance. It implies that diverging tendencies and interests may be reconciled into balance and harmony with each other. The multistakeholder approach is fundamental to this idea, which ideally serves to articulate the priorities and interests of each party. Although parties cannot entirely agree on responsibilities or priorities, they can reach a partial consensus about global issues and development problems. The idea of economic and social values as intricately related to each other, and as unattainable without each other, is part of all Forum settings. In so doing, it seeks to play a role in the alignment of different and sometimes divergent interests and values by assembling groups and people from various spheres of society.

From Cologny and into the World

The activities of the WEF are funded by one thousand companies, called “members” and “partners,” which are some of the largest and most highly ranked companies in their fields of business. The highest governing body of the WEF is the foundation board, comprising a smaller number of highly influential persons some of whom are chosen from the funders. In 2015, the Forum was formally recognized as an international organization (“other international body”) by the Swiss government18 and describes itself as

the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation. The Forum engages the foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas. . . . Our activities are shaped by a unique institutional culture founded on the stakeholder theory, which asserts that an organization is accountable to all parts of society. The institution carefully blends and balances the best of many kinds of organizations, from both the public and private sectors, international organizations and academic institutions.

We believe that progress happens by bringing together people from all walks of life who have the drive and the influence to make positive change.19

The WEF has approximately six hundred employees, and counting, located at the headquarters in Cologny outside Geneva and in regional offices with small staffs in Beijing, New York, San Francisco, and Tokyo.20 Aspiring to be truly global, people of around sixty different nationalities staff the organization.21 The localities in Cologny have been expanded to house the constantly growing number of staff and address heightened security demands. As visitors approach the entrance to the building, armed guards check their identity, their WEF contact, and purpose of their meeting. After they pass through the gate, they enter the building via a security-screening portal, which checks their bodies and bags for potentially dangerous objects. Inside the building, a receptionist again records their names and the names of their WEF contacts and asks the visitors to sign in to get a visitor’s badge. In the waiting lounge, floor-to-ceiling windows offer a breathtaking view of Lake Geneva, and multiple WEF publications are provided, for visitors to browse.

The WEF describes itself as politically neutral, in the sense that it is not tied to any national, political, or partisan interests. It operates as a think tank, networking among and influencing corporate leaders and top politicians, NGO heads, and academics. Although best known for its Annual Meeting in Davos, it regularly hosts a large number of more informal and private meetings around the world, such as the Annual Meeting of the New Champions (targeting emerging economies), the Young Global Leaders Meeting (focusing on promising young leaders), and meetings on the topics of social entrepreneurship and scenario planning. In addition, its strategic insight teams produce reports—for instance, in the fields of economic competitiveness, global risk, and scenario thinking. Moreover, the WEF strives to be and already functions as a private organizer for diplomatic efforts on a range of topics. Such issues as climate agreements, the Israel–Palestine conflict, the war in Syria, global trade tariffs, corruption, and sustainable management of the Arctic are on its agenda. Reports, ratings, and indexes are some of the specific outcomes from these activities, as are ideas about how to move forward and advocate them.

In order to attract people to work for them, engage in panels and deliberations, craft reports, advocate, and, ultimately, instigate change, the WEF organizes its participants into communities. These are, in essence, loosely organized groups of people joined together around issues. The communities constantly vary in number and composition. The Forum’s one thousand funding corporations form one of the core communities. They are key players in the Forum’s activities, and their financial and organizational support is essential for the Forum’s mission.

The Global Future Councils (previously called the Network of Global Agenda Councils) make up another key community. The councils are a network based on invitation-only individuals that study the most pressing issues facing the world. In each of the councils, we find about fifteen to twenty designated” experts,” altogether some fifteen hundred “premier thought leaders,” who come together to engage in interdisciplinary dialogue, shape agendas, and drive initiatives.22 Another highly exclusive community is the Informal Gathering of World Economic Leaders (IGWEL). At the Annual Meeting in Davos, political leaders from the G20 and other relevant countries and the heads of international organizations engage in high-level dialogues facilitated by the IGWEL program.

In contrast to these high-profile communities, the Forum also works to create networks for less established but promising individuals. The Global Shapers Community comprises over six thousand young people, and counting, based in more than 450 cities in 170 countries and territories. Organized into a network of “hubs,” dedicated to creating local impact, they are meant to constitute a source of grassroots knowledge and global youth perspectives. Global Shapers, as the name suggests, are expected and encouraged to “take action on issues they care about and positively disrupt global policy discussions.” The Forum of Young Global Leaders, in its turn, organizes over eight hundred “enterprising, socially-minded men and women selected under the age of 40, who operate as a force for good to overcome barriers that elsewhere stand in the way of progress.” The Forum presents the community as made up of “leaders from all walks of life, from every region of the world, and from every stakeholder group in society.”23

The Global Leadership Fellows community is another highly prestigious community comprising students admitted to the three-year educational program—the Global Leadership Fellows Programme of the World Economic Forum. The program combines intensive on-the-job experience, a learning curriculum, coaching and mentoring, and access to an extensive network of alumni. The program aims to prepare its chosen fellows for leadership in both public and private sectors and to work across all spheres of a globalized society.

The communities are not open for all to join. Candidates are proposed through a qualified nomination process and assessed according to rigorous selection criteria, as set by the Forum.24 The exclusivity of participation and meeting attendance is often motivated by a perceived need on the part of the WEF to create “safe places” for the invited people to talk freely, under the observance of the Chatham House Rule.25 In addition, since individuals do not attend as representatives of their nation-states, corporations, NGOs, or political parties, they are expected to feel the need to be thus protected from a broader audience. In the network-like organization, the WEF thus consciously creates an organized network of safe places where invitees can meet in an open and trusting manner.

A New Site for Global Normativity

Surprisingly, given the massive attention of the Davos meeting, the particular organizing model of the Forum largely slips under the radar of both media and academics. Furthermore, the Davos meeting is often misinterpreted as a top meeting among politicians, similar to the summits of the UN, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or the G20. In fact, the constellation of participants at the Davos Annual Meeting tends to show a majority of business leaders and only a smaller ratio of politicians. According to our calculations, based on a sample of participants in WEF meetings (not merely in Davos) from 2011 to 2013, 41 percent were businesspeople, 16 percent high-level public officials, 16 percent NGO representatives, and 13 percent academics. Media represented 7 percent of the participants, supranational (European Union) politicians 6 percent, and religious community members 1 percent. Among these participants, the average age was fifty-six years. Most commonly, the participants had a PhD or master’s degree, which in part or fully was completed at one of the world’s ten highest-ranking universities. In 2011, 17 percent of all participants were women; by 2017, the figure had increased to 28 percent.26

The WEF is not alone in its endeavor to provide other ways of dealing with the implications of globalization and global governance challenges. Over the past few decades, we have indeed witnessed a formidable growth in the number of organizations with global governance ambitions and a large number of experiments with other forms of governance. Actors in this domain work by crafting and diffusing norms, standards, and codes of conduct and by establishing political programs for the transformation of minds and actions.27 To use the terminology of sociologist Saskia Sassen, new “sites of normativity” are appearing on the global scene, with power and resources to influence, shape, and fashion the thoughts and actions of others.28 The existing system of multilateral governance is thus paralleled and transgressed by a rapidly increasing number of organizations without a legal mandate to influence global governance yet with the ambition to do so. These organizations must carve out, construct, and expand their position and mandate. The Forum may therefore be seen as part of an emerging transnational domain that is still under construction.29

In the larger picture, the WEF also bears witness to the emergence of a powerful new actor on the global political arena: the think tank. On such pressing issues as climate change, security, and trade policy, think tanks are becoming prominent voices. The UN Climate Meeting in Doha in December 2012, for example, hosted a number of think tanks, including the World Resources Institute, a global think tank that works with governments, businesses, and renowned individuals to promote a low-carbon future. Another example of the recognition of the role of think tanks in global governance is their positive mention in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Think tanks are in this text seen as significant organizations for policy impact at the national level and critical for achieving a better understanding of the efforts required to mobilize the means of implementation—financing, technology, and trade.30

Think tanks were long considered of little importance to social science researchers. A pronounced increase in their sheer numbers,31 however, coupled with their more articulate ideological positions and intensified advocacy efforts, has contributed to rising academic interest. They offer an institutional innovation that can seamlessly merge research, publicity, and advocacy; in this context, research may become a weapon of political struggle, championing a vision for society and public policy.32 Yet there are a number of unaddressed questions concerning the role of think tanks as political actors. One of the most urgent questions addresses the forms of legitimacy, authority, and power being constructed by such organizations as the WEF, the Atlas Network, the Club of Rome, and RAND Corporation.

Criticizing the lack of attention given to the way “organizations mold their environments,” organizational scholar Stephen R. Barley has mapped organizational links between think tanks and other corporate-funded political actors in the United States.33 Barley’s findings demonstrate how such organizations nationally have succeeded in exerting growing political influence over the past few decades. In this context, think tanks may be viewed as boundary-spanning organizations, specializing in mediating relationships among larger, more established policy fields.34 At the global level, the WEF serves as a boundary-spanning think tank involved in the brokerage of transnational knowledge domains, contributing in the long run to developing new, transnational forms of power, authority, and legitimacy.35

Part of the influence of an organization such as the WEF has to do with the webs of knowledge created around it. Through its activities, the WEF contributes to the establishment of global policy networks and the circulation of knowledge, information, and expertise within those networks. It therefore contributes to the establishment of “epistemic communities” for policy coordination.36 International relations scholar Diane Stone has convincingly argued that such “knowledge networks are a form of power.”37 The WEF, with its extensive and engaged networks of organizations and associated individuals, has emerged as a central hub in the churning of policy-relevant ideas and knowledge and as a central arena where knowledge from various sources is brought into contact and used to further policy ideas based on assemblages of knowledge.38

A challenge for students of governance as pursued by the WEF is that the conventional notions of policy networks, advocates, lobbyists, interest groups, or other notions used to capture organizations and actors with aspirations to influence global governance are no longer able to do the full job. They fail to capture the flexible use of professional affiliations, roles, and skills that comprise new types of policy networks and brokers.39 And at the organizational level, the power to influence policy and politics derives increasingly from the capacity to create and strategically deploy networks and alliances between diverse forms of organizations. This power builds on a relational capacity, residing in the modes of connections and relationships that are established to produce and leverage specific constellations of knowledge and ideas.40

To analyze contemporary power, we also need to rethink the relationships between the state and market actors and the concepts of politics and nonpolitics.41 We view the organization of the Forum as constituted in and through relationships of collaboration, negotiation, and strategic communication in a larger field of organizations.42 In this sense, the WEF is a brokering organization, strategically situated as an intermediary between markets and politics on the global arena. Its influence is based on extending its agentic capacity through its network of individuals and associated organizations. This brokerage generates a “partially organized network,”43 coordinating other actors by establishing and maintaining communities and creating a variety of forms of membership and providing access to certain kinds of resources.44 In this field, the WEF obtains authority over other actors only if it is recognized as legitimate.45 The authority of the WEF is therefore fragile: it does not enjoy an official political mandate but must continually construct and maintain its authority and legitimacy. How it builds this recognition is a question of organizing for effective leverage and diffusion of its ideas to the world’s top leaders and next-generation leaders. Most important, the Forum’s power and authority are built on seductive forms of communication and decisions about agenda setting, meeting participation, and proposed actions made at its own discretion. For this system to work, the discretion of the participants is also required. These practices constitute the base of the WEF’s discreet power.

The Seductive Organization

In spite of its potent and spectacular image, the WEF is a small and lean organization, with no legal mandate in international governance. It is not an elected body; heads of state did not create it; it is not a meta-organization, with representatives from various nations. To extend its base and its authority, the WEF must build on a strategic effort to create networks and communities across organizational boundaries. In practice, this entails propelling its ideas and visions through these networks and communities not by coercion but by seduction—that is, by attracting others to its ideas and visions and motivating individuals to work for them and to want the outcomes the WEF wants. The key concept here is seduction, built on ingredients such as status, exclusion, and discretion.

Seduction, as recognized by political scientist Joseph Nye, implies the exercise of a subtle, soft form of power—the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction, not by force.46 At the personal level, we all know the power of attraction and seduction. In politics, as Nye shows, seduction is a staple and tends to be associated by an “attractive personality, culture, political values and institutions.”47 In his view, “seduction is always more effective than coercion.”48 Many values propelled by globalizing organizations and in international diplomatic efforts, such as democracy and human rights, individual opportunities, and sustainability, are deeply seductive. Soft power means getting others to want the outcomes that you want, to move in your direction. It is thus a form of cooptation and constitutes, in Nye’s words, “real power.”

By way of seductive communication, the Forum aims to attract attention, interest, and engagement and ultimately persuade and convince other individuals and organizations that certain propositions are more reasonable than others. The exercise of such soft, discreet power entails that resources of varying kinds (for example political, financial, social, ideational, knowledge based) are converted into realized power in the sense of obtaining desired outcomes. This in turn requires well-designed strategies and skillful leadership. Global seduction, as exercised by the Forum, thus involves a set of communicative strategies aimed to persuade and convince others to go with the propositions that emerge out of the meetings.

By seduction, the Forum sets the stage for its specific discretionary governance: a form of governance that extends indirect social and communicative influence to larger organizational matters. It involves the exercise of influence and power in line with one’s own judgment but outside the realm of customary democratic monitoring.49 In its efforts to convince its participants and the world at large of the strengths of the normative foundations of the Forum, it employs strategies of communicative seduction and persuasion that are reminiscent of approaches within public diplomacy. Indeed, the rise of the WEF on the global governance scene is linked to developments in the field of diplomacy, and more specifically to the growth of public diplomacy—targeting relations between a diverse set of actors involving not only state officials but also unofficial groups, organizations, and individuals—as a significant reflection of the changing world system toward a multipolar order.50 One may also note the increased importance of commercial diplomacy as a growing field of interaction between public and private actors.51

The WEF’s many forms of socializing, associating, networking, and interacting—the staged ceremonial events, the seminars, the small team deliberations, the backstage meetings, the pleasant business lunches, the smooth cocktails, and the extravagant parties—are characteristic of the seductive organization and provides it with a social dynamic and sense of uniqueness.52 Although WEF meetings and events may appear as somewhat frenzied and disorganized, with people moving back and forth among panels, seminars, networking events, and parties, they are tightly orchestrated. All Forum employees and participants at the events have a mission and understand their role. Each mission, whether it is about initiating a discussion around youth entrepreneurship in West Africa or about investment opportunities in the Arctic, has a long-term and a short-term goal. Each accomplished event brings in return new network contacts, novel information, increased knowledge, or attractive business opportunities.

The particular form of socializing cultivated in and around the Forum centers around the act of seduction, based on selection and elevation of “the best” leaders, experts, and brains. The organization carefully screens, picks, scrutinizes, and evaluates the suitability of its potential invitees. No one—and there are no exceptions—can enter the meeting grounds or participate in seminars without an invitation. The screening process may take a year and involves checking the potential invitee’s background, education, work experience, expertise, credentials, credibility, and integrity. The checkup entails references and a process in which the need for the person is carefully weighed. Paola Pakulsky, manager of one of the in-house departments at the Geneva headquarters, is in charge of this process. She is a robust and well-versed woman in her early fifties, with accommodating and considerate manners. She explains:

We’re basically a marketing function in the sense that we provide support to the teams, whether it’s the business teams or those dealing with other constituents, in helping them to engage, then, the right people into the right agenda. So our motto is “right person at the right time, in the right agenda.”53

The screening and selection process is given priority in event planning because the credibility and legitimacy of the Forum relies largely on the performance of the invitees. The other side of this matter is that they need to feel chosen, desired, and wanted. The careful selection process assists in conferring on the invitees a sense of being elevated above the common person and given status distinction. As sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has noted, such processes function simultaneously as a system of power relations and a symbolic system in which minute distinctions become the basis for social judgment.54 The badge of entrance provided to those who pass the test is indeed a marker of status. Many invitees have conveyed to us the exhilarating sense of elevation they received from having been invited and being present where the action is, among the selected few. Being on the spot with Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, singer-songwriter Bono, or Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg is different from watching them on television and social media. The WEF badge and their presence at the Forum work as a sort of aphrodisiac, giving them the hype. After having been at the Davos meeting, Amir Shihadeh, the curator of the Amman hub of the Young Global Shapers, a young people’s community organized by the Forum, conveys this feeling:

Literally, get ready for the best experience in your life! As a Global Shaper, the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland is the most amazing, passionate, awe-inspiring, phenomenal, and influential event you’ll ever attend in your life. Be “present” in both your mind-set and heart while in Davos. Grasp every moment and “internalize” it. Take many “mental pictures.” This meeting will remain with you forever, Insha’Allah (God willing).55

The craving for attention and the allure of proximity is a never-ending process. The invitation is not a given and is reconsidered every year and for every event. Neither is an invitation to participate in one of the working groups or communities a permanent invitation; it is contingent on performance and the priorities of the Forum. With the invitation comes the never-ending anxiety of being thrown out of the circle of nobility and losing the status and privilege that come with belonging. The community of invitees can thus be described as an aspirational class, continuously striving for inclusion.

Enticement in the Emirates

As ethnographers, we have experienced what it means to be enticed by the relevance and grandeur of the organization and its events, but also—and primarily—what it means to be excluded and dismissed. Beyond being a signature ethnographic experience, this double bind is crucial to understanding the operational strategies of the WEF. The following sequence provides a sense of the double character of the Forum—inviting and alluring yet excluding and withdrawing.

We are all dressed up, in a taxi on the long Al Mina Road in Dubai. We’re wearing somewhat uncomfortable high-heeled shoes, tight-fitting pencil skirts, business blouses, and elegant scarves. We have decided to pay a visit to the WEF “brain trust meeting,” and we do not want to be met with suspicion or even hesitation because of how we look. We anticipate that we will fail, though, at least in part. Handbags show that we are researchers of some type; they are overloaded with equipment: computers, smart phones, papers, pens, and other necessities.

The Forum staff refer to the Dubai event as the “brain trust meeting,” but the proper name is the Summit on the Global Agenda. To this meeting, about fifteen hundred of “the world’s best brains” are invited each November to brainstorm and work toward the agenda for the coming Annual Meeting in Davos in January. As usual in the WEF environment, the summit comprises a mix of politicians, civil society people, researchers, and people from funding corporations. (In Chapter 4, we discuss how they come to be identified as the best brains.) Together they contribute to “a network of invitation-only groups that study the most pressing issues facing the world.”56 “All brilliant,” one of the staff from the Geneva headquarters described them. And as later vouched for, in the assessment of the Global Agenda Councils, “These councils . . . are creating powerful ideas that are having a measurable impact.”57 By creating what is termed “thought leadership,” the councils are meant to influence global public policy, as the results will spread through all possible channels.

We don’t feel particularly brilliant, however. As usual, we had tried to be granted access in advance by contacting the Geneva headquarters, informing them about our research interest and the value of giving the world a research perspective on the nature of these meetings. Having been denied, we decided to go anyway. In the taxi on our way to the meeting space, we are not at ease; in fact, we’re rather disillusioned and crestfallen. We have no idea how far our efforts to come closer to the meeting core of discussions would take us this time. Will the travel be worthwhile? Will our stylish but uncomfortable shoes help us gain entrance? Our Istanbul endeavor, attending the WEF Regional Meeting in Istanbul a few months ago, had been successful in the sense that we had been able to socialize with staff and participants in the designated networking area set up for the meeting in the hotel lobby. Our recollections of the Turkish military police and the hotel entrance fortified with sandbags and automatic firearms make us a bit shaky, though. What will it be like this time? Is it really a good idea to gate crash a secluded event like this in Dubai?

Surprisingly enough, things go smoothly. Despite the guarded security check, designed and ornamented in the shape of an Arab arch, equipped with screening belts resembling those at airports, we are not searched for the obligatory badges (Photo I.1). We glance at each other with relief and walk ahead steadfastly. We are in again, at least in the networking area. This time the networking area has been established in a plaza-looking room, with a high ceiling, wall-to-wall carpeting, and openings to a garden terrace where lunch is being served. The area is full, mostly of men in costumes or thawbs, but also women in high heels with expensive handbags. Most of them are showing hair and ankles, but some heads are covered by hijabs, and a few are completely covered by niqabs (Photo I.2).

We make our way toward the garden terrace, resembling scenery from “A Thousand and One Nights,” where an extravagant lunch buffet has been set up. Plates in hand, with a small selection from the buffet, we approach one of the tables, where a group of men and one woman have started their lunch and their lunch conversation. They are all smiling kindly at us. After a while, one of them turns our way, introduces himself as Mathew Tong, and wonders who we are. As usual, we tell the plain truth: “We’re researchers from Stockholm University, Sweden, with an interest in understanding how WEF constructs and contributes to global politics.” We know from numerous earlier encounters that our chance of keeping his attention is dependent on our short introduction. We would have a window of fifteen to twenty seconds when he would decide if we are interesting enough to talk to.

Mr. Tong, an academic of British origin, an unflappable-looking, gray-haired, and stylish man in his early fifties, apparently finds us entertaining enough and starts describing himself and his relationship to the WEF. He has been part of the brain trust summits for five years and considers himself something of a veteran. He quickly explains, in an ironically kind, smiling, and playful tone, that he never knows what, if anything, they are achieving. “It’s a very intangible thing,” Tong says. “Mostly I believe that it’s about trend spotting. You get a sense of what’s going on.” The rewards for him are also quite intangible, with a vague sense of contribution once he returns home. “What happens, happens in the councils,” he concludes. So he had skipped the first plenary and gone swimming instead. “I am very shallow,” he admits. “In general I believe that people come hoping to be invited to Davos. By participating over and over again, they aspire to qualify as participants at ‘the summit of summits.’” Tong says that he is certainly hoping to be invited to Davos, although it has not happened yet. When he received his first invitation to Dubai, he said, he had thought that the whole thing was a setup, some kind of a scam. So he phoned the Forum and asked them to e-mail him again. With a half smile, he claims that he has a vague sense of why he was invited: because “I do have a small impact in Hong Kong. I am kind of big there, but it’s nothing, of course.”

After the short lunch conversation, Mr. Tong invites us to follow him when he returns to a session in the actual council meeting. Experienced as we are with WEF rules, we follow him to the badge checkpoint, with little hope for making it inside. As we assumed would happen, we are not allowed to enter. The guards are firm. We cannot be let in.

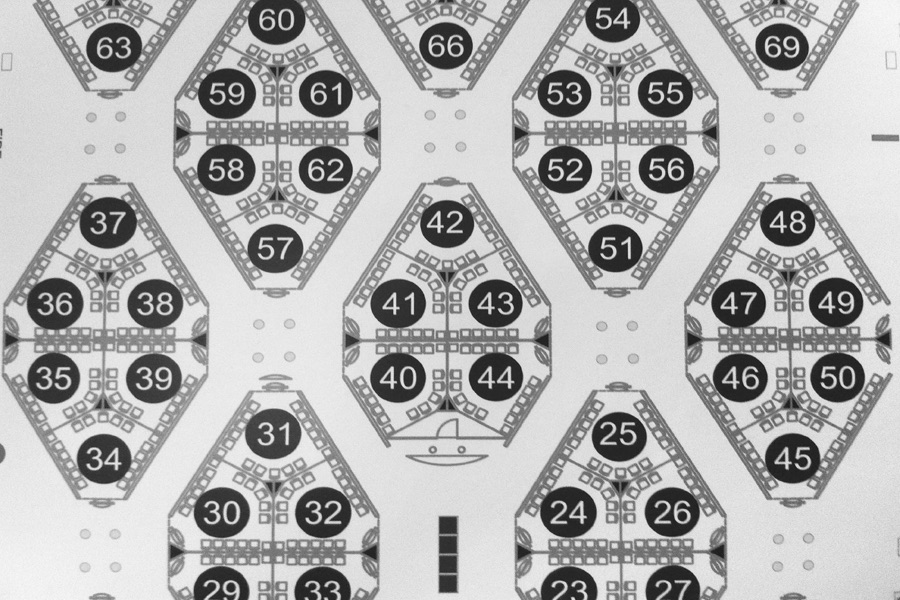

At the council meeting entrance, there is a large signpost with an illustration of a schematic beehive, representing a map of the cells in which each council has its meeting. The map is made to look like the inside of a beehive. All the small groups, normally between ten and fifteen persons, including the WEF moderator, meet in these small areas. The idea is that these cubicles shall be closed enough to enable group processes to begin easily, a member of the WEF staff explains in a later conversation, but open enough to allow people to move between the small cells, so that both ideas and people may flow freely (Photo I.3). Struck by this image, standing at the entrance to this social beehive but not being allowed in, we have nothing to do but grasp our cell phones from inside our handbags and take pictures of what we believe to be a portrait of the desired organizational model: the beehive, a key metaphor for the organizing process of the WEF, simultaneously a model of and a model for the organization.58

Mathew Tong hurries inside the beehive to his group. We strike up a conversation with Ruby Balancona who is overseeing badges and the handing out of black conference briefcases with the WEF logo printed on them. She believes that it would in theory be possible for us to participate and initiates the process, trying to sort something out by talking to Simon Kaminsky, one of our earlier interviewees from Cologny. After a few minutes she comes back and says that it is not in her or Kaminsky’s hands; we will have to talk to Jean-Luc Bosser who is managing the GACs. Fortunately, we already have a meeting scheduled with Mr. Bosser set up at 4:00 p.m., ninety minutes later. With the groups now in session, the networking area is quite calm. Coffee and water are served from a bar, and we help ourselves while waiting.

We use the time to take notes with our reflections on the situation. What are the chances of gaining entrance? We should try to see this from their perspective. Why would they not let us in? Is this their way of holding us at a distance, saying neither no—so they may still maintain the image of transparency—nor yes. It’s a little Kafkaesque, we think, invoking a senseless, disorienting complexity. Is research by gate crashing really the only solution for a social scientist interested in understanding and presenting the Forum to the outside world?

At 4:00 p.m. Jean-Luc Bosser appears and guides us to one of the meeting rooms. He is a composed and anxious-appearing man in his forties, with distinct facial features that clearly express distress at our presence, with a stern look. He closes the door to the event firmly, saying, “No one gets in, no matter who they are and how interested they are in the meeting.” He gives us the example of the president of Mexico, who apparently also wanted to join on his own initiative but was refused. “As I have explained earlier, we cannot open the door to all people who want to join,” he states emphatically. He is swallowing hard. Disappointed, we leave the conference premises, walk up to the adjacent Mina A’Salam Hotel, where we have an appointment scheduled for next morning with a GAC member we had met before, to check on where the meeting will take place. The summit is not yet over.

Such was our experience of the Forum: at once an organization with the aspiration to gather people “from all walks of life” to work together “to improve the world,” by addressing pressing global challenges, and, on the other hand, an organization that prides itself in inviting only “the best brains” and the most resourceful corporations to its meetings behind closed doors. The selectivity and hype cultivated around the organization, the urgency, and the glitz work to further the voice of the WEF in the global political domain. It is, in essence, a truly seductive organization.

Book Outline

We intend this book to provide a narrative of the Forum that captures central dimensions of its workings as an organization. We have also chosen to weave the more analytical discussion into our ethnographic experiences, so as to render the seemingly abstract an embodied quality.

In Chapter 1, we provide a view of the WEF as an ethnographic field and describe our experimental methodological design. We highlight the varying strategies we used to approach the organization—ranging from gate crashing to taking on the insider’s role—and the different types of engagements we experienced in meetings and conversational interviews. Apart from displaying the experimentation with the ethnographic method that this research involved, we emphasize the close intertwining of methodology and theory and suggest that what one may learn from denials, rejections, and failure may be just as informative as what is learned by full access and participation. By attempting to study the WEF, by being denied, rejected, and sometimes also welcomed, we learned about the politics of discretion in practice.

Chapter 2 looks at the liquid mandate on which the WEF bases its activities. Against the background of lacking a formal mandate, we describe how it is possible for WEF to position itself as a legitimate actor at the global level. This brings to the fore the seductive strategies in which the Forum is so proficient. With the “right” people attending, legitimacy rubs off on the organization. The network of contacts that WEF organizes, characterized by opacity and a high degree of global sway, is a consequence of the corporate-based mandate they enjoy. We discuss discretionary governance as the specific form of governance by which the Forum operates. In light of the relative lack of democratic characteristics such as representation and accountability, we argue that this type of governance entails a withdrawal of the elites.

In Chapter 3, we describe the authoritative capabilities of the WEF in terms of communicative power. Based on our ethnographic observations and descriptions, we reveal how the activities of WEF are consequential precisely through its communication. Communication, we suggest, is the means by which organizations are designed, created, and sustained and the base of power and authority. At WEF, communication entails working on setting precedence in issues related to global policy and markets, to frame and articulate issues, problems, and solutions. The agenda setting may appear not to involve conflict on the surface. However, the lack of open conflict does not necessarily mean lack of conflict; in fact, conflict is recurrent around the Forum.

Chapter 4 takes a closer look at how the status machinery of the WEF works. The Forum provides an exclusive and closed arena on which a level of hype, urgency, and topicality is produced. The processes by which individuals are selected to participate in discussing, debating, and advocating solutions to urgent global problems are meticulously prepared. The Forum draws into its orbit carefully chosen individuals who are organized into communities of expertise; they engage in cultivating a brain trust, highlighting and celebrating particular individuals, ideas, and actions. We reflect on these processes and how they work to distance the Forum and its selected crowd from the public. By this process, the Forum creates and enhances status distinction and contributes to the formation of a new transnational elite—what we call an aspiring class.

The activities that are distinctly formatted around the future—mobilizing the young and presenting future scenarios—are discussed in Chapter 5. The future is a signature theme at the Forum, one that serves to articulate and postulate future perspectives, agendas, risk, and generations. The emphasis at the Forum is on preparing for the future as it unfolds. In this chapter, we show how the risk scenarios and the future communities are ingredients in the aspirations of shaping the world in a specific direction. They articulate a particular form of anticipatory knowledge, geared to contribute to the shaping of political priorities and agendas, reflecting WEF’s central values and priorities.

Chapter 6 unfolds the sometimes conflicting political underpinnings of the Forum. The Forum advocates a specific form of neoliberal thought combined with third way social democracy. This combinatory approach also promotes a set of ideas regarding the role of business in politics, by which economic and social values are seen to be seamlessly aligned. Together these ideas underpin a type of politics that is characterized by a postpolitical paradox in which conflict is seemingly turned into consensus, at the same time as the all-inclusive multistakeholder model turns out to be a differentiating and conflicting force.

In the Conclusion, we return to the exclusivity of the Forum, its liquid mandate, seductive strategies, and discreet power. We reflect on the workings of discretionary governance and the question of how, and if, global politics is possible. And we address what the role of the Forum is at the level of global politics. The WEF is a response to the fragmented global predicament, calling for more transnational cooperation. As a model for future governance, there are democratic challenges but also opportunities for markets, policymaking, and diplomatic relations. The WEF continues working toward its goal “to improve the world” and to show us one alternative organizational order.

As we reach the end of the book, we hope to have conveyed how the Forum, together with its funders and invitees, continuously strives to create a fragile political mandate with a significant global sway. This form of power, however soft and discreet it may be, turns out to be seductively sharp.

1. World Economic Forum (2017a, 1).

2. Schwab (1988).

3. Schwab (1988, 1).

4. The identities of all informants are confidential, and all informant names are pseudonyms. The only exception is Klaus Schwab, who appears under his own name. More details about research confidentiality are provided in Chapter 1.

5. Hylland Eriksen (2007); Hannerz (1996).

6. Scholte (2005).

7. Garsten and Sörbom (2017b).

8. Interview, March 14, 2013.

9. Schwab (1971).

10. World Economic Forum (2010a, 7).

11. Code of Ethics—The Davos Manifesto.

12. Code of Ethics—The Davos Manifesto.

13. Garsten and Sörbom (2014).

14. World Economic Forum (2010), www.weforum.org/about/history.

15. Schwab (1988).

16. World Economic Forum (2010), accessed May 4, 2016, at www.weforum.org/about/history.

17. Schwab (2004).

18. At its meeting on December 17, 2014, the Federal Council recognized the WEF as an “other international body” as defined in the Host State Act (HSA, Sr 192.12) and approved the agreement (accessed March 30, 2017, at https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/dokumentation/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-55987.html).

19. World Economic Forum (2018), accessed January 15, 2018, at https://www.weforum.org/about/world-economic-forum.

20. More regional offices are to come, as laid out in Schwab’s 2020 vision (Schwab 2015).

21. World Economic Forum (2017c), accessed March 27, 2017, at www.weforum.org/about/careers.

22. World Economic Forum (2017d), accessed March 27, 2017, at www.weforum.org/communities/global-agenda-councils,

23. World Economic Forum (2017e), accessed March 27, 2017, at www.weforum.org/communities/young-global-leaders.

24. The Global Leadership Fellow Programme is in this sense different, since it is open for application. The admission decision is then made internally at the WEF. Likewise, the Global Shapers community is open for application through the local hub, which has some leeway in deciding on admission.

25. Chatham House Rule states that anyone who comes to the meeting is free to use the information from the discussion, but not allowed to reveal the source.

26. See the appendix for a fuller description of these figures.

27. Djelic and Sahlin Andersson (2006); Djelic and Quack (2010); Garsten and Sörbom (2017b).

28. Sassen (1998).

29. Ruggie (2004).

30. United Nations (2015).

31. McGann (2017).

32. Smith (2007, 89). See also Arin (2013); Denham, Garnett, and Stone (1998); McGann (2007); Medvetz (2012a, 2012b); Rich (2004); Stone (1996); Weidenbaum (2011).

33. Barley (2010, 777).

34. See Medvetz (2012a).

35. In a similar vein, other scholars have described how think tanks may influence political and other agendas, and thus achieve power and influence. Mirowski and Plehwe (2009) describe, with the example of the Mont Pelerin Society, how the core ideas of neoliberalism were planted and distributed in “networks of neoliberal partisan think-tanks.” Richardson, Kakabadse, and Kakabadse (2011) outline the mechanisms of influence at work in “the transnational power elite,” with a focus on the Bilderberg group. Researching Bible advocacy in England, Engelke (2009) maintains that the establishment of a think tank was part of what he terms “strategic secularism,” a process by which religious actors work to incorporate secular formations into religious agendas. Medvetz (2012a), in his thorough overview of think tanks in the United States, argues that the ambiguity of the think tank is the very key to its power and influence.

36. See, for example, Haas (1992); Stone (2005).

37. Stone (2002, 9).

38. Carroll and Carson (2003).

39. As social anthropologist Janine Wedel (2009, xi) argues, “The frameworks and terms that we’ve long used to understand power and influence are not longer sufficient to explain what is happening.” These new agenda-wielding players, Wedel succinctly contends, “actively structure, indeed create, their roles and involvements to serve their own agendas—at the expense of the government agencies, shareholders, or the public on whose behalf they supposedly work. These players not only flout authority, they institutionalize their subversion of it.”

40. Consequently, in terms of power and authority, we stress a constructivist dimension, departing from the notion of power as suggested by Foucault, according to whom the term “designates relationships between partners” (Foucault 1982, 786). See also Lukes (2005, 12) and Luhmann (1975). We develop our understanding of power at length in Chapter 3.

41. Along the same lines, sociologists Miller and Rose (1992, 175) contend that “political power today is exercised through a profusion of shifting alliances between diverse authorities, to govern a multitude of facets of economic activity and social life.”

42. Medvetz (2012a) has also taken a relational view of the role of think tanks.

43. On the concepts of “partial organization” and “partially organized fields,” see Ahrne and Brunsson (2011).

44. Garsten and Sörbom (forthcoming).

45. Cf. Emerson (1962).

46. Nye (2008).

47. Nye (2004, 95).

48. Nye (2012, x).

49. Scholars in different domains have used the term discretionary governance to denote forms of governance that in some way go beyond the conventional in relying on informal and unofficial procedures and are not subject to established forms of democratic control or regulation. Hagendijk and Irwin (2006) discuss discretionary governance in the context of the governance of science and technology, and Heydebrand (2013) addresses the issue with regard to interactive new media.

50. See, for example, Melissen (2005).

51. See, for example, Naray (2008).

52. The notion of sociality here is meant to capture the different sets of concrete social relationships that develop around social activities (Pink, 2008, 172). Our interest in sociality thus reflects an interest in ongoing substantive social action rather than fixed or social relations defined a priori. Furthermore, sociality reflects an engagement in shared worlds of meaning and understanding, most readily emerging out of and apparent in social relations (cf. Vergunst and Vermehren 2012).

53. Interview with Paola Pakulsky (September 18, 2012).

54. Bourdieu (1987).

55. Shihadeh (2015).

56. World Economic Forum (2016e), accessed April 26, 2016, at www.weforum.org.

57. World Economic Forum (2014, 4).

58. Geertz (1972).