In 2005, China’s then Minister of Commerce, Bo Xilai, tried to convince Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) representatives in a Paris conference that China did not pose a real threat to manufacturing industries in other countries. “China must export 800 million shirts in exchange for the value of only one Boeing A380 aircraft,” he said. The comment was intended to relieve the worry of conference representatives from industrialized countries in light of China’s large trade surplus. When the statement was later released in the media, however, it aroused strong sentiments from the Chinese public. “China is absolutely miserable,” lamented one web commentator. “China cannot be the permanent factory for the world,” wrote a Yale-educated Chinese intellectual, who later turned his comment into a book (Xue 2006). Many voices questioned the sustainability of relying on cheap labor and razor-thin profit margins, calling instead for fundamental changes in the manufacturing industry.

To get the story straight, the challenge for China—and for other emerging economies throughout Asia, Latin America, and Africa today—is not simply a matter of switching from making shirts and shoes to producing computers and airplanes.1 In fact, China’s largest manufacturing industries have already changed from textiles to computers and mobile phones.2 Between 1995 and 2006, China’s share of the world’s high-tech exports has increased almost eightfold; since 2006, the country has become the world’s largest high-tech exporter, surpassing Japan, the United States, and the European Union (Meri 2009). Globalization has undoubtedly contributed to the ascendance of China as the world’s manufacturing titan. The problem, rather, is “high technology but low (or no) innovation.” The fragmentation of the manufacturing process allows the country to engage in the mass production of high-tech goods with little innovation and much reliance on the low cost of labor. With labor and material costs sharply rising, strikes increasing, export markets shrinking, and currency appreciating, policy makers have started to realize that the economy has hit a turning point that needs to go beyond the “middle income trap.”

The Chinese state, to its credit, is actively trying to address the problem. Just as they created preferential policy packages to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) decades ago, the Chinese state has recently launched a big transition. The central state issued a combination of government funding, taxation, land and utilities reduction, and tariff exemption, among others, to promote innovation by their own industrial firms, 93 percent of which are domestic private businesses. The government ranked development zones, assigned and evaluated policy targets, and admonished firms that they ought to exit the “race to the bottom” competition, invest in innovation, and move up the value chain. Indeed, Chinese officials constantly cite Japan and South Korea of the 1960s as role models, where a developmental and authoritarian state used industrial policies as carrots and sticks to push firms to develop global competitiveness.

The success of such state-led transformation is based on two assumptions: that local officials have the incentive to implement such policies and that these policies, when implemented, will work. These assumptions, surprisingly, are also often suggested by many studies of industrial and development policies. In reality, however, when policies are implemented, they produced a highly mixed and confusing picture, causing intensive debate among scholars and policy observers. There were pessimists who showed considerable doubt about China’s ability to build its indigenous competitiveness beyond just being the world’s workshop, optimists who saw Chinese firms as an ultimate beneficiary of global production with or without state support, and alarmists who took the state’s plan seriously and expressed deep concern about the implications of the state-sponsored plan for the market economy (Arayama and Mourdoukoutas 1999; Chan and Ross 2003; Steinfeld 2004, 2010; Gilboy 2004; Branstetter and Lardy 2006; Breznitz and Murphee 2011; Herrigel, Wittke, and Voskamp 2013; Brandt and Thun 2010; McGregor 2010; Miles 2011; Dean, Browne, and Oster 2010; Bradsher 2010).

The goal of this book is not to side with any of these groups but to actually explain the source of the confusion. It explores the roots of substantial variation in implementing economic policies across this continent-sized economy. Even within the same industry and at similar levels of economic conditions, heterogeneity persists throughout main manufacturing cities. Among other contributions, this study unpacks the ways in which local bureaucrats interpret state upgrading policies, fight for resources, and form coalitions within a globalized context where foreign and domestic businesses coexist. It also unfolds in detail why well-intended, seemingly unified national policies end up producing heterogeneous and often counterproductive outcomes. Whereas, in some cities, government advocates for reforms were able to seize the initiative to introduce a matrix of new policies and garner resources, the same initiative was retarded by the vested interests and bureaucratic competition in other cities. Although government support in funding and tax cuts succeeded in nurturing motivation for upgrading among local private businesses in some localities, it dampened their incentives to invest in learning and innovation in other localities, deprived them of developmental spaces, and left firms in a continuous, desperate race to the bottom competition.

Such variation needs to be understood in light of China’s two stages of transformation, the attraction of FDI in the first stage and the push for local upgrading in the second stage. The strong bias in favor of foreign firms throughout the 1990s and early 2000s has made China the largest recipient of FDI among developing countries. With inward FDI to China reaching an annual record of US$105.7 billion and foreign invested enterprises (FIEs) producing 88 percent of China’s $282 billion high-tech exports, global firms have become part of daily economic life (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS] 2007, 2011; Ministry of Commerce [MOC] 2008). For this reason, China presents a new generation of “globalized” economies—notably Brazil, Russia, India, China (BRIC)—in which FDI played a much more essential role in comparison to the last generation of East Asian developers (notably Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) (Hsueh 2011; Tsai and Pekkanen 2006).

In the mid- to late 2000s, however, the central state gradually phased out preferential policies for FIEs and used similar policies in government funding and tax breaks to promote indigenous technology competitiveness, especially among domestic private enterprises. Yet instead of replacing the previous pro-FIE policies, the old and new initiative coexisted with tension in localities, creating competition for shifting resources among government–business coalitions who saw themselves benefiting from different policy paradigms. This book finds that the type of alliances that local officials formed with FIEs in the earlier stage shaped the interpretation of policies, the patterns of bureaucratic competition, the dynamics of resource allocation, and local development trajectories in the later period. That is, even if one could argue that foreign capital is not as important as it was in the 1990s, the potential strength of vested interests that it cultivated among the local bureaucrats and the incentive structure it built for domestic businesses remain path dependent in the 2000s.

The influence of globalization on policy outcomes, however, was made possible only through local bureaucratic agents. In an authoritarian country where businesses do not have direct channels to influence the party state, local state officials are the direct agents who conduct economic policies and advance the interests of their business clients.3 This book finds that local bureaucrats who are employed in the Chinese state apparatus—reaching 14 million people in 2010—developed their own ways of attracting global capital and seeking domestic upgrading by adapting and tailoring state policies.4 Their interests, policy preferences, and developmental strategies were deeply embedded in the norms and institutions of local capitalism that had been developing for more than a century. During different periods of time, these local forms of capitalism drove bureaucrats to define their business clients; to advocate, resist, or revise the emerging policies of upgrading; and to coordinate the production relations between foreign and domestic firms.

The influx of foreign capital conditioned local transformation, but such a transformation is enabled by local bureaucrats. The interaction of the two generated profound consequences. In the process of creating local policy, the role of foreign capital in exports and the concentration of large foreign firms intensified or mitigated the struggles among government departments over resources, providing far more obstacles in some cities than others for the allocation of budget for technology upgrading. In the process of policy implementation, the offshoring strategies of foreign firms and the government officials’ active embracing of strategies shaped the configuration and sequence of industrial development in a city, which facilitated or dampened the effectiveness of development policies at the firm level.

As such, state-led development is not best understood as Beijing using policies to directly influence local firms, at least for the majority of manufacturing industries.5 Rather, the process of creating and implementing state-led policies involves introducing new dynamics to complicated contexts where persistent local conditions and varied degrees of globalization mutually accommodate each other. This book examines precisely how the logic of globalization was incorporated into fragmented forms of local political economy and how the ambitious state-led development agenda was also interfered with and altered by foreign capital at the local level. As such, seemingly well-intended state policies may generate unexpected outcomes in localities where local government institutions and production relations were mismatched with the task of the industrial transformation at hand. The project, thus, calls for new ways of understanding globalization, state-led development, and comparative capitalism.

State-Led Development with Complicated Implementation

The first major goal of this book is to unravel the politics of economic policy implementation in authoritarian multilevel countries. The finding that “economic policies are political” (Alt and Crystal 1983: 33) has long been acknowledged but with few analytical frameworks developed for authoritarian regimes, where the state is not submitted to the electoral pressure of societal groups. When such topics are discussed in the context of the authoritarian developmental states of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan in the 1970s, the assumption is often that the state can enforce its strategies once policies are formed by an autonomous and capable bureaucracy under the guidance of a pilot development agent. This assumption is premised on the coherence of the state, a relatively clear goal of national development, and domestic ownership of businesses (Johnson 1982; Amsden 1989; Wade 1990; Evans 1995). As such, the issue of “policy implementation” by local government agencies is largely neglected. To the extent that it is discussed in the context of embeddedness and networks of the state with businesses, the assumption is often that the policy processes run directly from the national government to businesses.6

This book challenges these assumptions and draws attention to the myriad of strategies that local government agents have employed to manipulate national economic policies in China, where national initiatives are implemented as mandates through a province–prefecture (city)–county–township–village hierarchy. Many studies have recognized local governments in China as important units of analysis for economic outcomes and the wide regional variation when carrying out central policies (Oi 1999; Whiting 2001; Ong 2012; Rithmire 2014, 2015; Shen and Tsai 2016). They argue that in an environment lacking the rule of law and protection of private property rights, local governments assume a crucial role through orchestrating market production, selectively providing subsidies, and coordinating relations among enterprises (White 1988; Oi 1999; Walder 1995; Blecher and Shue 1996; Blecher 1991; Duckett 1998). Even within the same region, one often finds conflicting stories of local states being development promoting and development thwarting at the same time (Unger and Chan 1999; Sargeson and Zhang 1999; Segal and Thun 2001).

This book resonates with the emphasis on the local state, but it further opens up the black box of local politics and goes beyond demonstrating local variation. It contributes to the understanding of the sources and mechanisms of local policy variation. Studies of industrial, economic, and technology policies typically focus on showing how such policies vary across several locales in China (Breznitz and Murphree 2011; Steinfeld 2010; Thun 2006; Brandt and Thun 2016). Although these studies touch on a number of the sources of variation, such as Maoist legacies in the economic structure or the localities’ relationship with the central government, they often do not systematically articulate the mechanisms through which these factors affect investment and economic policies. In particular, the issue of local governments’ decision making and implementation (that is, why they choose to embrace or resist certain policies and why they distort policies toward one direction rather than others) are underinvestigated. This lacuna is especially surprising, given the widely observed phenomenon of policy adaptation and selective implementation (Tsai 2006; O’Brien and Li 1999).

Once the issue of complicated implementation is brought into studies of state-led development, as this book does at China’s prefecture city level, one finds that the willingness of government to devote resources to technology upgrading and innovation is an outcome of bureaucratic competition based on the fragmented interests of the department agencies and their long-established business clients. That is, whether local advocates for new state initiatives were able to garner resources and build institutions cannot be taken for granted. It is a process requiring careful scrutiny against the institutions of cadre evaluation and structure of “fragmented authoritarianism” governing bureaucratic politics in local China before one is able to confidently discuss implementation at the industrial and firm level (Chen 2017).

Globalization, FDI, and Local Coalitions

The breaking down of the assumption on a coherent and single-level state is an important step in understanding the complication in implementing industrial policies and development policies in general. What further complicates the case, however, is the systematic influx of FDI. Unlike the previous generation of catch-up economies in East Asia that limited the entrance of foreign capital (despite promoting exports and trade), China has become an exemplar case of the “globalized” generation of countries including, among others, Brazil, Russia, Malaysia, and India.

These countries have seen an increase in FDI since the 1990s. The rise of global value chains and production networks has fragmented the production process and created manufacturing opportunities through outsourcing and offshoring (Whittaker et al. 2010; Chen 2014). The active attraction of FDI by national and local government officials and development zones also contributed to the globalized context. When globalization became not only a context but a “constitutive element” of the economy, regulating and coordinating the relationship between foreign and domestic firms became a key challenge for local governments (Hsueh 2011; Ye 2014; Yeung 2009).7

Policy and scholarly debates have ensued. Although not widely noticed in Western scholarship, the debate in light of earlier dependency theory and the so-called Latin Americanization of China reached its zenith among Chinese scholars and observers in the 1990s. The concern they expressed was that China’s overwhelming reliance on attracting FDI would produce a series of negative consequences, including trapping domestic producers in maquiladora-style sweatshops and increasing levels of inequality (Gilboy and Heginbotham 2004). This was certainly going against the broad trend of returning to a neoliberal globalist ideology at the time, which cast FDI in positive light (Williamson 1989; Little 1982; Myint 1987; Bauer 1981; Krueger et al. 1983; Bhagwati 2004). At the same time in Western academics, a spate of “second image reversed” works has started to examine how economic openness influences domestic coalitions and politics, among which a growing body of literature has emphasized FDI.8 Some have investigated the general economic influence of FDI on domestic growth and development. Others have looked at the political influence of foreign investors in facilitating liberal-oriented reforms and practices, curbing (or increasing) corruption, shifting national debates, and challenging central state authority (Frieden 1991; Zweig 2002; Huang 2003; Gallagher 2005; Pearson 1991; Malesky, Gueorguiev, and Jensen 2014; Sheng 2010; Wang 2014; Pinto 2013; Zhu 2017; Long, Yang, and Zhang 2015).

Regardless of the explanatory objectives of previous works, many of them make their argument based on observations of an overall structural variable, often the value of FDI as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in a locale.9 When explaining the outcome of domestic upgrading policies, however, one finds that FDI, as a general structural factor, cannot account for local differences in a universal and linear manner. In fact, it will be shown that cities with similar levels of FDI dependence (and a similar level of economic development) often end up with contrasting degrees of support for new policies. This is a clear case in which we need to unravel the in-depth mechanisms through which FDI is exerting the influence.

Rather than assuming the direct influence of all foreign firms by inferring backwardly through statistical results, this book finds, through intensive field research as well as quantitative evidence, that the majority of foreign firms do not have direct access to city decision making or the possibility of using money to buy votes for their favored politicians (Wang 2014). Instead, they exert their influences through local bureaucrats, the real decision makers in local economic policies. The local state still matters in the new wave of globalization. Given the relatively weak role of industrial associations in aggregating and representing business interests, businesses tend to form patron–client relations with the bureaucrats who regulate them. At the city level, the influence of foreign firms is indirect and significant only when they are able to contribute to cohesive and strong vested interest coalitions among the city bureaucrats. At the firm level, the influence of offshoring strategies on the effectiveness of policies and domestic private firms also clearly differs between the large and small foreign firms. Their impact is uneven, and whether they “crowd out” or “crowd in” domestic businesses varies.

As such, similar to the need to break down the state, one should also disaggregate FDI. The influence that globalization and foreign capital have on state-led development cannot be simply captured by a sweeping claim. Instead of assuming that foreign capital completely dominates the local development agenda as classical dependency theory would predict or dismantling the state power as a neoliberal force, this book illustrates the more nuanced way in which various facets of globalization interact with the local state in shaping coalitional politics behind China’s upgrading policies.

The Argument

The major argument of this book is that the campaign of FDI attraction in the 1990s was a critical juncture for the subsequent campaign of industrial upgrading in the 2000s, as the type of foreign firms with which the local governments forged alliances shaped the coalitional politics of decision making at the city level and laid the structural foundation for policy implementation at the firm level. When other factors are controlled, cities that initially focused on attracting large top-ranked global firms were surprisingly less able to garner resources and effectively implement policies in comparison to those started with smaller firms at the lower position of the value chain.

The first important influence of FDI attraction lies in the policy-making process in response to the rise of a paradigm for domestic competitiveness. Potentially, this paradigm could be—and has been—viewed as a de facto change of government-supportive policies (such as government funding and tax breaks) from foreign firms to domestically owned firms. Foreign influence on domestic policies is most significant when it sharpens bureaucratic struggles between winners and losers, and such influence is most powerful when it has political value to local elites. The new initiative in upgrading is most likely to be seen as a threat by a vested-interest coalition among city government bureaucrats in charge of international commerce to fight against policy implemented by the newly emerged domestic technology department. The international commerce bureaucrats are more likely to form a cohesive coalition when foreign firms overlap with exporters in a city. At the same time, such a coalition is more likely to win the competition for resources controlled by top leaders when foreign firm production in the city is concentrated in large firms. Combined, these two conditions contribute to cohesive and strong vested interests. In cities that started by attracting smaller foreign firms and with more domestic producers participating in production, the configuration mitigated the cohesiveness and strength of vested interests. Bureaucratic competition over resources was kept within the issue area of domestic technology, which allows advocates for reforms to make progress.

The second crucial role of FDI attraction lies in the implementation of policies at the firm level. In cities where the local government prioritized the attraction of large foreign firms at the top of the value chain, they settled on a group offshoring strategy. This strategy created a hierarchical segregation between foreign and domestic enterprises, deprived the latter of developmental space, and trapped them in a continued race to the bottom competition. The structure of production drastically reduced the effectiveness of government upgrading policies (including funding and tax cuts) at the firm level, dampening the incentives of firms to upgrade. By contrast, in cities where local government predominately attracted small “guerilla investors” at the bottom of the value chain, the major production strategy connecting foreign and domestic firms was subcontracting. This strategy broke the hierarchical segregation and enhanced the effectiveness of the upgrading policies by strengthening the incentives of domestic firms to move up the value chain. The processes of policy making and policy implementation were mutually reinforcing.

The interaction of global capital and local political economy has therefore produced four crucial dimensions that have influenced development trajectories, which are fleshed out by four subarguments of the book. First, the increase in inward FDI gave rise to investment-seeking states across China, which created beneficiaries among local bureaucrats. Second, the export share of FDI and the concentration of foreign firms affected the varied responses of bureaucrats to the rise of domestic upgrading and cultivated competing government–business coalitions within the city bureaucracy.10 These coalitions shaped the amount of resources that a city was willing to invest in domestic technology. Third, the type of foreign firms a city attracted also influenced the effectiveness of implementing upgrading policies at the firm level, as well as local firms’ upgrading capacity, which largely reinforced decision making at the city level. Finally, when placing regional development trajectories in a much longer historical context beyond the contemporary era, I find the ways in which government–business relations took shape and their development priorities to be deeply embedded in varieties of local capitalism.

Globalization and the Rise of Investment-Seeking States

Although the year 1978 marked China’s opening to foreign investment, it was not until the 1990s that China had a systematic influx of FDI throughout the country. As soon as the central state gave the green light to local authorities for approving FDI, Chinese officials throughout the country launched a zealous campaign of FDI attraction. Using measures such as land discounts, aggressive tax cuts, government funding, and bank credits, local officials went out of their way and competed to bring in foreign investors as a way both to establish political achievements under the cadre evaluation system and to promote local growth. During this period, China saw the rise of international commerce departments in most of the city governments, as these bureaucrats controlled most of the “resources-bearing” policies that they are able to grant to FIEs. At the same time, these bureaucrats also became the major beneficiary of the FDI-attraction paradigm.

The type of investments that local officials prioritize, however, diverged across major cities. In some cities, such as Suzhou in the Yangtze River Delta, officials prioritized the attraction of large-scale multinational corporations (MNCs) at the top of global value chains. In some other cities, such as Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta, officials brokered informal contracts with many small foreign firms established by “guerilla investors.” The time period of FDI attraction in the 1990s indeed laid the industrial basis for local manufacturing industries over the next decade. However, more important and often unnoticed was the way in which a city government’s global allies affect coalitional politics and the implementation of policies. The distinct types of FIEs and their export activities in a city affected the patterns of bureaucratic competition within the fragmented bureaucracy for the period promoting domestic competitiveness. Furthermore, the rising offshore or subcontracting strategies and the configuration of production interfered with the effective implementation of policies at the firm level further down the road.

Globalization and Bureaucratic Coalitions

The feature of “fragmented authoritarianism” and the pressure of the cadre evaluation system in Chinese bureaucracy led to rampant competition among bureaucrats (Manion 1985; O’Brien and Li 1999; Li and Zhou 2005; Liu and Tao 2007; Landry 2008; Shih, Adolph, and Liu 2012; Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988; Lampton 2013; Mertha 2006, 2009; Ang 2016). This book builds on previous works by showing how bureaucrats compete over power, policies, and resources, but it goes further to explore what difference this competition makes and how exposure to globalization complicates the policy process. China’s transformation from an FDI-centered development approach to domestic competiveness involves two major government agencies in a city, the international commerce departments who may see themselves as potential losers and the domestic technology departments who are potential winners. The features of foreign firms that bureaucrats attracted in a city shaped both the alignment of interests and the strength of coalitions behind the new policies.

Although the rise of the domestic competitiveness paradigm is often viewed as harmful to foreign firm interests, it is not necessarily perceived as being detrimental to international commerce bureaucrats because their function is to regulate FIEs and exporters, which can be domestic businesses. The policy is viewed as uncontroversially detrimental only when the entire realm of international commerce perceives their interests as being tied with foreign firms and rallies together as a vested interested group. When FIEs and exporting firms overlap in a city, international commerce bureaucrats become the primary regulators for foreign firms; hence, they see foreign firms as their long-term business clients. The rise of new policies hurts their interests and arouses a coherent voice of opposition. In contrast, even when a city has many FIEs, if it has less overlap between foreign firms and exporters, international commerce bureaucrats can have clients that are domestic exporters as well as foreign firms. This is a situation that mitigates the foreign–domestic struggle, which builds bridges rather than walls. In this case, most bureaucratic competition has been kept within departments in charge of domestic technology and the implementing agencies of the new policy, which essentially facilitate the carrying out of policies.

In addition to FIE–exporter overlap, when FIE production in a city is concentrated in a few large global firms, vested-interest groups are found to have more bargaining power—and are, therefore, more likely to be strong—compared to those in which output is shared among small and medium foreign firms. City party secretaries and mayors have tended to favor and develop close relationships with bureaucrats who are able to help significantly and rapidly boost city indicators. In economic decisions over budget and resource allocation, the vested-interest group is able to use the existence of large foreign firms and wield more persuasive power with top city leaders. Such a strong competitor diverts resources toward other policy goals and marginalizes bureaucratic reformers who were the “institutional builders” for domestic private firms. This circumstance prevents the domestic technology coalition from increasing resources for science and technology upgrading that they can use to establish local funds, industrial parks, or innovation platforms.

As such, foreign firms became a valuable resource on which bureaucrats draw to interpret policies, boost policy targets, and fight for resources that are favorable to their own coalition. This book, at the same time, avoids a deterministic approach and elucidates the way in which the features of domestic bureaucratic politics are internalized and channel the impacts of foreign capital, making bureaucratic competition an obstacle to policies in some cities more than others.

Globalization and the Effectiveness of Policies for Local Firms

In addition to local coalitional politics in city policy making, foreign firms that were attracted to a locality also interfere with the process of policy implementation at the firm level. Although the most heightened period of FDI attraction took place in the 1990s, once FIEs came in, they shaped the local configuration of production throughout the 2000s. That was why government policies that use funding and tax cuts to encourage local firms to engage in technology upgrading did not always translate into results. Even when controlling other features, government funding and tax cuts are much less likely to generate upgrading incentives in cities that are dominated by large-scale FIEs compared to those with smaller guerilla FIEs. This gap is found to be quite significant, even among coastal cities with similar levels of economic development.

More specifically, taking China’s largest manufacturing industry (that is, electronics) as an example, the book found that, when a city government allied with large global firms, the emerging supply gap between global and domestic firms encouraged both the government and MNCs to promote a group-offshoring strategy, which co-outsourced foreign suppliers to the same region, based on the leading firms’ connections with global suppliers and the deliberate planning of bureaucrats in the international commerce. This strategy ended up occupying the middle and lower levels of the production chain with foreign firms, which amplified the power disparity between global and local firms, squeezed and segregated the latter into the bottom of the value chain, and forced them to compete for cheap labor and limited production opportunities. Under such circumstances, even when domestic technology officials used government funding and tax breaks to encourage upgrading behavior, such as investment in research and development (R&D) and patent applications, they still could generate hardly any incentives and behavior among domestic firms.

By contrast, smaller FIEs were situated at the bottom of the global value chain and did not have the organizational resources to initiate group outsourcing. Over time, they found local subcontracting to be a more attractive option. This allowed the local government to use the subcontracting needs of smaller global firms to help build local capabilities. This upgrading strategy broke the hierarchical segregation between global and local firms, undermined the power disparity in local production, and reserved more developmental and upgrading space for local producers. At the same time, the strategy of starting from the bottom broadened grassroots state business developmental coalitions that resisted the predesignation of business winners. Domestic producers demonstrated a much higher level of ambition to invest in learning, and the same policies of government funding and tax cuts were found to be much more effective to generate firm-level upgrading incentives. The firm-level outcomes, in turn, reinforced either a narrow vested interest benefiting from hierarchical segregation of foreign and domestic firms or a broader coalition that bridges interdepartmental competition in the process of budget allocation at the city level.

Globalization and Varieties of Local Capitalism

Placed in a comparative context over long stretches of time, the book traces the divergent paths of local economic transformation to historically entrenched patterns of local capitalism, a process in which the formation of bureaucratic preferences is essential. As such, it uncovers the nature of capitalism in authoritarian yet globalized China. Globalization has generated important influences on local development in the contemporary period, as previously mentioned. However, from a longer time horizon spanning the past century, it is the local form of capitalism that selectively incorporated globalization into its own logic by interest-driven bureaucrats.

The perspective advanced here draws on the “varieties of capitalism” approach used to study advanced industrialized countries and, increasingly, East Asia and Latin America (Hall and Soskice 2001; Vogel 2006; Schneider 2013). I apply the varieties of capitalism approach to the subnational level and show the historical origins of such capitalism prior to the contemporary period (pre-1978). On this point, I build on other works that have long noticed the persistent patterns of local economic orders, such as Locke (1995) on Italy and Herrigel (1996) on Germany.11 Furthermore, in contrast to the varieties of capitalism approach, I emphasize local bureaucrats’ preferences and their reaction to centrally driven policies in shaping local capitalism, rather than firm-level institutions in finance, employment, and coordination, as such institutions were still fairly weak in China during the periods of the 1990s and 2000s. Although localities dominated by top-down modes of capitalism bear certain similarities with Schneider’s (2013) argument of “hierarchical capitalism,” my emphasis has been on the state’s deliberate selection of such business alliances and the subsequent consequences of the development strategies on domestic bureaucratic decisions and domestic businesses.

In the much-heated debate over Chinese capitalism, some scholars see China’s development trajectories as relying on bottom-up processes involving grassroots-level private businesses, whereas others focus on the rise of top-down state capitalism based on public ownership. A third group noticed China’s transition from one to the other and has discussed the complicated relations between the two.12 This book shows that capitalism has taken a variety of forms, top down or bottom up, at the local level within the same country. I argue that the preferences of local bureaucrats emerged from varied degrees of political mobilization and different levels of responsiveness to upper-level political signals during the state-building process. It is these bureaucratic preferences, rather than economic structures measured by enterprise ownership, that ultimately define local bureaucrats’ choices of businesses allies, their relationship with the major businesses, and their strategies of promoting local development.13

As such, my argument also goes beyond the conventional market versus state dichotomy and the active versus dormant state distinction. Rather, it shows that local state officials have been actively involved in the economy throughout China but that they can generate very different policies and state–business relations that are embedded in bottom-up, as well as top-down, modes of capitalism.

Using the Jiangsu and Guangdong regions as important examples, I trace the emergence, survival, and reinforcement of bureaucratic interests and the sticky patterns of government–business relations through comparative historical analysis across four periods, including the late Qing and early republican period (1895–1920), the Mao era (1949–1978), the post-Mao period (1978–1990), and the globalized era (1990–present). I found that, in each period, the degrees of political mobilization for development shaped the goals that bureaucrats prioritized, the policy tools used to achieve developmental goals, and the breadth of state–business coalitions. In Jiangsu, where bureaucrats were historically motivated by political promotion, they sought narrow alliances with big business at the top of the hierarchy and habitually launched top-down campaigns to accomplish central policy mandates. In Guangdong, where bureaucrats were historically driven by practical economic gains, they protected small businesses with diverse flexible measures that often circumvented central policies. The rise of top-down and bottom-up modes of capitalism in the two regions produced rewards that, in turn, reinforced the distinctive local state preferences embedded in the local form of capitalism.

These historically entrenched patterns of state interests and state–business relations survived during the Maoist period of state building and were carried into the contemporary period, which conditioned and contextualized the different global business allies that local governments choose and their subsequent response to domestic upgrading in the twenty-first century. Along the line of historical institutional perspective, preferences, institutions, and development certainly reinforce each other (Thelen and Steinmo 1992; Mahoney 2000; Pierson 2004). However, even the emergence of the critical juncture in the current period (that is, localities’ different priorities, with FDI attraction following China’s embrace of globalization) still reflects the continuity (although not the complete stagnation) of local legacies.

Thus, what I argue in the book is quite different from a scenario where local forms of capitalism are either homogenized by forces of globalization or demonstrate permanent resistance to globalization (Andrews 1994; Hall and Soskice 2001). Rather, I show how local capitalism is able to incorporate globalization into its own trajectories by helping to advance the interests of bureaucrats. As regions with different foreign capital responded to the upgrading initiative by devoting more or fewer resources to the upgrading initiative, and as the logic of global production interacted with local upgrading policies, the produced feedback loop that justified city-level policy making in the short run reinforced bureaucratic preferences in the long run.

Such alliances between local bureaucrats and global firms, however, generate unintended consequences on policies and often distort the incentives of domestic producers in a way that is not anticipated by the central state. In particular, although regions with a top-down developmental approach were able to produce stunning industrialization before the globalized era (such as within the Sunan area), they fell into the pitfall of cultivating narrow developmental coalitions due to bureaucratic competition from the vested interest department and the group-offshoring strategies of leading global firms. In contrast, the fortunes reversed for regions that are embedded in the bottom-up mode of capitalism, as they were faced with more favorable patterns of bureaucratic competition and subcontracting strategies that were more conducive to cultivating upgrading incentives among local producers. The local state, in other words, implemented industrial upgrading policies in response to the call of the central state, but the success of such policies was determined by the long-term local institutional environments, which were created by the local state itself over long stretches of time and were not entirely anticipated by the upgrading policies themselves.

The insight generated from this study, however, is not restricted to the uniqueness of the Chinese context. It sheds light on East Asian and Latin American countries as well. The advantages of a particular type of local capitalism for developing local competitiveness are not permanent and have undergone changes with shifts in the global context. During the previous wave of globalization (between the 1970s and the 1990s), promoting the exports of domestic firms was the major way of integrating into the global economy, and the penetration of FDI was highly restricted. The Northeast Asian developers, including Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, created miracles through institutions that supported major domestic winners at the top of the production hierarchy. The rise of FDI and global outsourcing from the 1990s onward, however, unleashed FDI and exports at the same time without a period that focused exclusively on exports. The entrance of global capital altered the microfoundation of state intervention in developing economies such as China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia in Asia and Brazil, Chile, and Mexico in Latin America. The globalized context within each economy has made the top-down pattern of capitalism much harder to mobilize the upgrading incentives of domestic firms. Among other factors, the state’s intention to promote upgrading has been largely complicated by the problems of coordinating foreign–domestic firm relations and at the same time struggling to exit the “middle-income traps” (Doner and Schneider 2016). There are, in short, no one-size-fits-all types of comparative institutional advantages for effectively implementing a local economic transformation.14

The Research Design and Methodology

To explore how the penetration of global capital influenced policy making at the city level and policy implementation among firms in the city, I use a mixed-methods approach. I develop my theory from qualitative data and comparative case studies before testing the argument across hundreds of cities and thousands of firms. This book uses the prefecture city level as the major unit of analysis, as the local variation of policy implementation is most significantly manifested at this level. The province level is simply too broad to capture the vast variation among cities, as will be shown. The county level, in contrast, often does not possess the decision-making power for many of the industrial policies concerning government funding and tax breaks for domestic technology, as Chapter 4 will elaborate.

I develop the theoretical arguments through controlled comparative case studies among cities with similar levels of economic development before testing arguments with quantitative data. The case studies are based on more than 270 in-depth interviews with local government officials and business managers (typically one to two hours long) in 18 months of field research throughout 2008 and 2011. To explore government–business alliances and patterns of bureaucratic competition behind the city-level decision making, I coded and analyzed the texts of 118 of the semistructured interviews with officials in the international commerce and domestic technology departments in the cities of Suzhou, Wuxi, Ningbo, and Shenzhen. Then the argument was tested by using newly constructed datasets that cover the jurisdiction of 300 prefecture-level cities (where statistical data exist) over the course of multiple years.

To investigate the effectiveness of upgrading policies among firms in a city, I similarly generated arguments through paired comparisons of cities throughout different stages of development, restricting the comparison to the electronics industry. The comparison draws on both in-depth interviews as well as an original survey of 200 firms.15 This was followed by a construction of unique measures of effectiveness for government funding and tax breaks and the testing of argument through a multilevel dataset that includes 159 cities (which are the ones that have the electronics industry) and 6,740 domestic private electronics firms. Finally, in tracing the historical roots of local variation and placing Chinese localities in a comparative historical context, I consulted a collection of local gazetteers, archives, and historical studies.

Plan of the Book

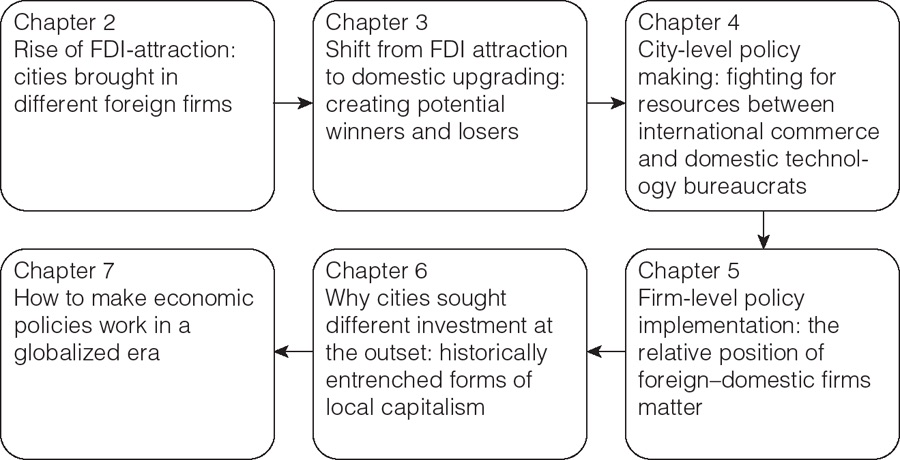

Chapter 2 examines the rise of the FDI-attraction paradigm at the national level and the emergence of local investment-seeking states in the 1990s. It explores in detail the varied strategies that city governments employed to attract foreign investors to launch the campaign of FDI attraction, ranging from tax cuts and land and utility discounts to industrial zone establishments. At one end of the strategic continuum are local governments that prioritized large leading multinationals that have been playing the role of the “dragon’s head” at the top of the global value chain whereas, on the other end, are cities where bureaucrats brokered deals with small-scale foreign firms established by “guerilla investors” at the bottom of the value chain through flexible arrangements.

Chapter 3 traces the relative decline of the previous FDI attraction paradigm and the emerging paradigm of domestic technology competitiveness, drawing on government documents, media text analysis, and interviews. The chapter then introduces the actors, the arguments, and the matrix of supporting institutions and policy tools underpinning the two policy paradigms. It draws attention to the coexistence of the two paradigms at the local level, where policies and institutions of FDI attraction profoundly affect the government’s response to domestic upgrading and their choice of development strategies.

Chapter 4 delves into the coalitional politics of policy making and resource allocation by investigating the response of city government officials to the rise of domestic technology in competition with the FDI-attraction paradigm. The chapter examines the patterns of bureaucratic competition between international commerce departments and newly emerged domestic technology departments and their respective business clients, including foreign and domestic firms. I explain the influence of FDI attraction on domestic politics by showing (1) how the overlap between FIEs and exporters shaped the degree of perceived threat and the cohesiveness of the vested interests in international commerce under the rule of fragmented bureaucratic competition and (2) how the existence of large FIEs strengthened the bargaining power of the vested interest bureaucrats against allocating resources to the domestic technology coalition. The direction and the magnitude of foreign influence, therefore, are filtered and channeled through local bureaucracy, giving rise to either deadlocked struggles between different departments or productive competition within the same issue area that facilitates the budget allocation for various forms of government funding, service platforms, and cost rebates for enterprise technology activities. The chapter develops a two-by-two matrix framework through comparative case studies and text analysis of interviews before testing the hypothesis using quantitative data across more than 200 prefecture-level cities in China.

Chapter 5 explains the effectiveness of policy implementation and the varied capabilities of city governments, using policy tools to generate firm-level upgrading incentives. Using China’s largest manufacturing and export industry—the electronics industry—as an example, the chapter compares the development of China’s two largest manufacturing cities, Suzhou and Shenzhen. It demonstrates how earlier patterns of FDI attraction and the prioritization of large or small FIEs gave rise to distinctive configurations of local production, as well as foreign–domestic firm relations. Through both in-depth case studies and hierarchical models at the city and firm levels, the chapter shows that a hierarchically segregated relationship started by the group offshoring strategy of large FIEs makes upgrading policies, such as government funding and tax cuts, less effective and dampens the innovation incentives for domestic private firms. By contrast, a more equal, broadly connected relationship started by the subcontracting strategy of small FIEs makes upgrading policies more likely to generate firm-level innovation behavior and contributes to the competitiveness of domestic private firms.

Chapter 6 traces the historical roots of local variation by chronologically and cross-sectionally placing China in a comparative historical perspective. It compares varieties of local capitalism in China across four periods, including the late Qing and early republican period (1895–1920), the Mao era (1949–1978), the post-Mao period (1978–1990), and the globalized era (1990–present). The chapter explores how the historically entrenched top-down and bottom-up modes of capitalism have conditioned local government preferences, as well as their reaction to centrally driven development initiatives, leading them to attract large or small foreign firms in the globalized era. The narrowly selective development strategies based on top-down capitalism were more effective in the industrial transformation during the preglobalized era before the 1990s. The influx of FDI since then, however, has unleashed new complexity so that cultivating bottom-up, broadly supportive networks with small firms was more likely to provide an institutional environment for the competitiveness of domestic private businesses.

Chapter 7 summarizes the findings of the book and highlights the implications of this study, both theoretically and practically, for the political economy of development in emerging economies. Starting with a story of Japan in the 1960s, the chapter shows the different ways that the Chinese economy integrated into the world economy. The chapter draws attention to how global production fragmented or integrated state agencies and businesses, shaped the ways they perceived their interests, and ultimately affected the political environments for domestic private firms. The chapter also discusses prospects and constraints for change for local capitalism. The chapter then broadens out to map major Asian economies in Northeast and Southeast Asia in a comparative picture. It finds that the earlier generation of developers was able to participate in global production by shielding the penetration of FDI to local settings. They were, therefore, far less sensitive to developmental coalition problems, compared with the current generation of developers that experienced high levels of localized global capital during their major growth periods.

1. For examples explaining challenges of industrial upgrading and transformation in other regions, please see Doner (2009); Cammett (2007); and Schneider (2013).

2. This observation is based on gross industrial values 1990 through 2008 provided by national statistical yearbooks in this period.

3. A business is identified as the client for a government agency if the agency’s function mainly involves regulating the business and the business also relies on that agency for preferential policies.

4. The number of employees in the state is provided by the NBS (2011).

5. For state-monopolized industries, such as electric power, oil, telecommunication, and aviation, central state industrial policies have a more direct impact on enterprises.

6. See Evans (1995) and L. Chen (2008). This body of literature also stresses the role of business and industrial associations bridging state and business, but this problem is not the most crucial for the overall context of China, as associations such as those play a much less important role in implementation compared to local governments. Further, even in the context of East Asian developmental states, the role of associations is to help devise better-informed policies, rather than really dealing with the issue of implementation.

7. Another important element of the global supply chains is the labor standard associated with the production. See Berliner at al. (2015).

8. For “second image reversed” literature, see Gourevitch (1978); Rogowski (1989); and Hiscox (2002).

9. One of the exceptions can be found in Malesky, Gueorguiev, and Jensen (2014).

10. For an excellent example of how business attributes affect the formation of coalitions within authoritarian regimes, see Pepinsky (2009).

11. Please also see Rithmire (2014) for analysis of these works in a comparative context with China.

12. For discussion along the Leninist top-down mode of capitalism in China (regardless of whether in a positive or negative light), see White (1988); Yang (2004); Huang (2008); and Pei (2006). For studies on the bottom-up development pattern of capitalism, see Arrighi (2007); Tsai (2007); Hamilton (2006); and Nee and Opper (2012). For a dialectic relationship between the two, see Heilmann (2011) and McNally (2012).

13. For past works that examine the role of the local state in the Chinese economy, especially the relationships among legacies of economic structure, current institutions, and the incentives of local officials, see Oi (1999); Whiting (2001); and Blecher and Shue (1996).

14. Comparative institutional advantages refer to the type of advantages that institutions provide for firms to engage in specific types of activities. See Hall and Soskice (2001).

15. This survey was conducted in collaboration with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2011 across China’s manufacturing cities.