Each year, a wide range of learners engage in a peer based program that supports school students in the greater Boston area to boost their academic learning outcomes. Breakthrough Greater Boston’s successful program inspires students from diverse backgrounds to learn more through building strong cross-generational learning relationships. Many subsequently aspire to be America’s future educators. Peers act mutually as learners and teachers, connected by core values that build a robust community environment.

Peer coaching processes are central to the success stories embodied in the Breakthrough Greater Boston not-for-profit organization.1 These relationships are essential to the well-being, learning, growth, and success that students from traditionally underrepresented communities experience. Success of the program extends well beyond school graduation, with 95 percent of these peer learners progressing to study at college. The value and attention paid to collaborative peer relationships has been increasing in both scholarly and practitioner circles. Whether in not-for-profit entities such as Breakthrough Greater Boston, in learning circles to support CEO development, or in health care, business, or government sectors, people are forming collaborative relationships to support their personal and professional development, and in turn promote organizational learning and change more effectively.

Scholars are observing these relationships in action and developing a body of knowledge now referred to as relational learning.2 Relational learning occurs in many familiar contexts, such as teacher-student relationships; leading transformational change in organizations; collegial relationships; a range of business relationships including those with direct reports, peers, and supervisors; mentoring; and developmental networks. This growing body of knowledge about how to build and sustain relationships that foster learning underpins peer coaching.

This book is about the principles and practices of peer coaching, a unique type of relational learning. We define peer coaching as a focused relationship between individuals of equal status who support each other’s personal and professional development goals. Peer coaching is a helping relationship between individuals at similar life or career stages to accomplish specific tasks or achieve developmental goals. Helping is an attitude that indicates a readiness on the part of each peer to explore issues in depth in a safe environment. The term helping does not refer to being an expert or knowing the solution, but to a process model, a dynamic. It refers to an inquiring mind that promotes questions, which in turn lead one’s peer partner to develop insight. The primary purpose of peer coaching is to promote goal-directed mutual learning with clear boundaries. The process is most effective when participants are intentional and share a desire to provide and experience reciprocal support. Together peers strive to establish high-quality relationships characterized by trust and open communication.

Rather than an expert/learner model, the peer coaching process creates an alliance between the partners so that both can continuously learn more quickly and efficiently. In practice, this involves sharing a vision for the relationship that involves supportive learning, active listening, and challenging each other. In essence, peers move from individual learning to relational learning, a change in focus from “you and me” to “we.” Both individuals and their organizations’ benefit.

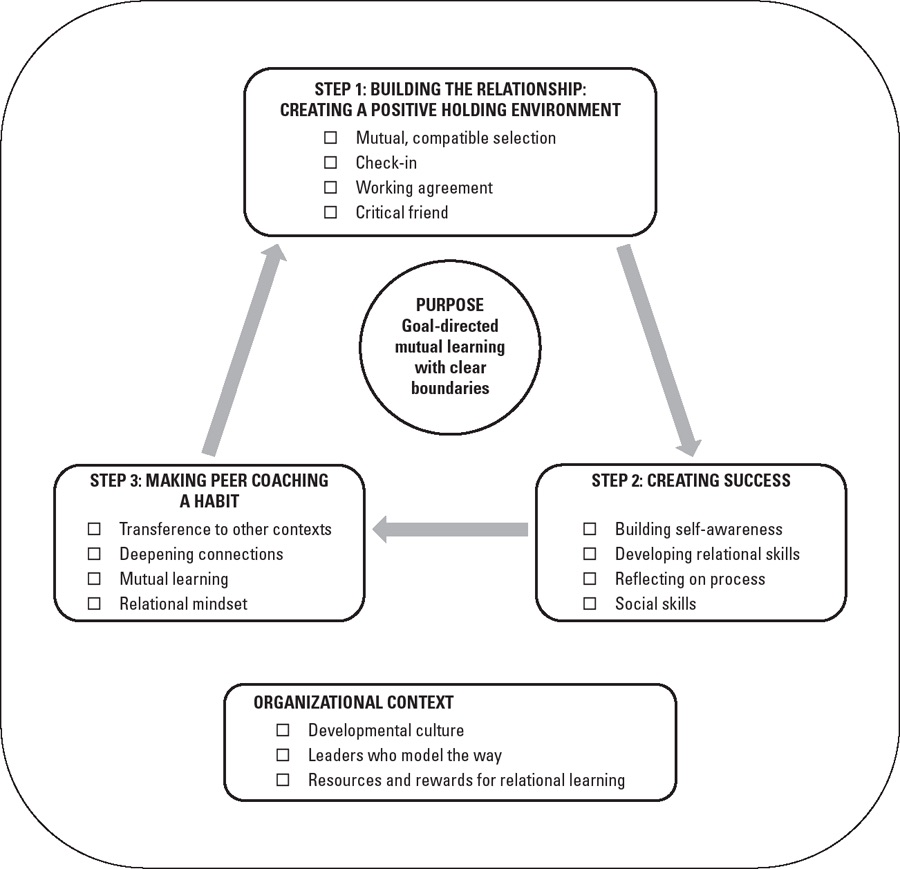

Let us begin with our 3-step Peer Coaching model:

Our model, first presented by Polly Parker, Tim Hall, and Kathy Kram in their article “Peer Coaching: A Relational Process for Accelerating Career Learning,” draws on our own practice and research, both of which are informed by theory and research on developmental relationships, developmental theory, helping relationships, and communication and relational perspectives. We will elaborate on our model to deepen its meaning and application and make it widely available to both scholars and practitioners. Our work builds on classic writings from Carl Rogers, Edgar Schein, and Kenneth Gergen and includes more recent work by these and other authors.3

Our purpose in writing the book is to highlight peer coaching as an effective, low-cost, and underutilized learning process that is available in abundance in most learning situations. We will define and discuss what peer coaching is and is not. We will provide a framework and guidelines for the effective use of peer coaching in work and educational settings.

Our 3-step Peer Coaching model highlights the importance of relational influences and embeds them in the learning process. To harness the potential of peer coaching, individuals must move progressively through steps that create a strong foundation, adopt a relational mind-set that values mutual learning opportunities, practice the skills that promote learning, and develop the habit of regular application. The 3-step Peer Coaching model provides the actions to move peer coaches toward a deeper understanding of how learning occurs and how personal confidence and capability grow.

The activities of Step 1 focus on building a safe environment in which peers will be able to reflect on their experiences, increase their self-awareness, and practice skills that enable continuous learning in the relationship. These activities build a holding environment that ensures safety, confirms each individual, and integrates challenge into the learning process.4

In Step 2 the behaviors focus on building success by applying and enhancing relational skills that boost personal and professional learning. These skills include critical reflection and social and emotional competencies that foster inquiry, experimentation, and practice.5 We introduce a relational communication approach to enhance interpersonal interactions in easy-to-use steps that can produce superior outcomes. Derived from the theory of coordinated management of meaning (CMM), these approaches describe how peers’ interpersonal interactions create meaning and learning as an ongoing and continuous process.6 Having honed their newly acquired reflection and relational skills, peer coaches often seek to apply them in a range of contexts.

In Step 3, peer coaches realize the potential of peer coaching after learning from their own experience of establishing learning relationships and extend relational skills to other relationships. Peer coaching is a habit when it becomes part of everyday practice.

In Chapter 1 of this book, we introduce peer coaching and the organizational or societal demands that make this relational learning process essential. In Chapters 2, 3, and 4, we present and discuss the fundamental practices of peer coaching, taking you through the 3-step Peer Coaching model in detail. Finally, in Chapters 5 through 8, we apply peer coaching in groups to inspire deep learning and to engage in everyday work life while minimizing the inherent risks.

In Chapter 1, we introduce readers to the VUCA environment in which all work now takes place and work relationships exist; a world that is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.7 In this increasingly complex and demanding environment, individuals are better equipped to cope and succeed when they develop vision, understanding, clarity, and agility as personal qualities. Continuous learning and development are essential to survival, effectiveness, and adaptation in most contemporary work contexts.8 Developmental relationships foster learning and provide effective ways to address these increasing demands. Peer coaching, in particular, enhances individuals’ learning and development while supporting similar growth for their peer partner. Learning to respond positively to uncertainty is easier when peers work together to seek understanding through reflection and clarifying possibilities rather than relying solely on their own personal experiences.

In chapter 2, we shift our focus to Step 1 of our model—building the relationship—and emphasize the essential foundations that build effective peer coaching relationships.9 Characteristics including trust, empathy, mutuality, and reciprocity help establish and build an enduring peer coaching relationship.10 Several models from CMM theory illustrate how peer coaches develop meaning and learning from their joint actions within the relationship.11 Applying the models enhances their relational competence.

Chapter 3 discusses Step 2 of our model—creating success—in which participants apply and develop skills that build self-awareness through self-disclosure and feedback, facilitate critical reflection, and together deepen confidence and competence in developing the peer coaching relationship. In practicing these newly acquired relational skills and actively applying CMM tools, participants can develop increasingly complex relational communication and coaching skills including self-regulation, deep listening, building empathy, and giving and receiving feedback.

Finally, in Chapter 4, Step 3 of our model—making peer coaching a habit—positions peer coaching as routine intentional practice in which peers apply relational coaching and reflective skills to other settings and collaborations. Peer coaches consider existing relationships at work and beyond the work context for further opportunities to use newly acquired and honed skills to enhance relational quality. They are also encouraged to initiate new relationships as they deepen understanding of their personal learning and development goals and the relational skills that they can offer to others. When peer coaching becomes a habit, the skills are internalized and transferable to other contexts. Given the persistent high learning demands in a VUCA environment, peer coaching is essential to improving performance and enhancing well-being for as many people as possible.

In the final chapters we apply our Peer Coaching model to increasingly common situations. For example, in Chapter 5 we discuss learning groups among peers, which proliferate in many forms today and include mentoring circles, employee resource groups, leadership learning groups, and industry-based learning circles. Peer learning in group settings allows members to benefit from the multiple perspectives of others with similarly vested interests. However, group dynamics are more complex than in a dyad and require participants to adapt each step of the Peer Coaching model to the group context. We examine the added complexities of peer coaching groups and discuss ways to leverage the mutual learning potential of these contexts.

In Chapter 6, we examine deep learning as an important potential benefit of relational learning. Differentiated from task learning, a deep learning process increases understanding about the self and prompts examining one’s existing mental models, attitudes, and patterns of behavior and their consequences.12 Outcomes of deep learning may be personally transformative in ways that enable an individual to have greater impact and experience in the world. We delineate the types of change that can occur and offer guidelines for how the reader can create conditions for deep learning in almost any context.

In Chapter 7, we discuss our vision of peer coaching as an everyday practice so that regular applications contribute to a culture of learning, development, and growth. Such an outcome is important to both organizations and individuals. We outline specific suggestions that workers, managers, leaders, and organizational development and human resource professionals can implement to support a learning culture for individuals, groups, teams, and the overall organization. You can benefit from or foster opportunities for peer coaching in any organizational position by enlisting help from others, offering help to another, and being willing to provide support more broadly. Increasing the number of proactive individuals to reach a critical mass can change workplace culture.

Finally, while peer coaching can be extremely beneficial to individuals and organizations, the process can break down and result in negative outcomes that undermine both individual well-being and organizational effectiveness. In Chapter 8 we offer some cautionary tales and explore them to raise your awareness of potential disruptions. Once aware, you can treat these cautions as a pivot point. We suggest strategies you can use to shift an undesirable pattern in the relationship or disengage from it altogether.

This book is written to provide you with the tools to develop successful peer coaching programs in your own life or workplace and to identify potential stumbling blocks as you become more comfortable with the steps in our approach. Each chapter offers practical suggestions for how to implement aspects of our model. Enjoy!

1. Breakthrough Greater Boston, http://www.breakthroughgreaterboston.org, accessed December 7, 2015.

2. J. E. Dutton and B. Ragins, Exploring Positive Relationships at Work: Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2007). See also W. Murphy and K. Kram, Strategic Relationships at Work: Creating Your Circle of Mentors, Sponsors, and Peers for Success in Business and Life (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2007).

3. C. Rogers, “Characteristics of a Helping Relationship,” in W. G. Bennis, E. H. Schein, D. E. Berlew, and F. I. Steele (eds.), Interpersonal Dynamics: Essays and Readings on Human Interaction, 3rd ed. (Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press, 1973), 223–236; E. H. Schein, Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1978); K. J. Gergen, Relational Being Beyond Self and Community (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

4. R. Kegan, In over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994). See also R. Kegan, L. Lahey, A. Fleming, and M. Miller, “Making Business Personal,” Harvard Business Review (2014, April): 45–52.

5. P. Parker, K. E. Kram, and D. T. Hall, “Peer Coaching: An Untapped Resource for Development,” Organizational Dynamics 43, no. 2 (2014): 122–129.

6. W. B. Pearce, “The Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM),” in W. Gudykunst (ed.), Theorizing About Communication and Culture (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014), 35–54.

7. B. Johansen, Leaders Make the Future (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2012).

8. J. Garvey-Berger, Changing on the Job: Developing Leaders in a Complex World (Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books, 2013). See also J. Garvey-Berger and K. Johnston, Simple Habits for Complex Times (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015).

9. E. H. Schein, Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2009).

10. J. E. Dutton and E. D. Heaphy, “The Power of High-Quality Connections,” in K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, and R. E. Quinn (eds.), Positive Organizational Scholarship (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003), 263–278. See also Dutton and Ragins, Exploring Positive Relationships at Work.

11. Pearce, “The Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM).”

12. R. Kegan, “What ‘Form’ Transforms? A Constructive-Developmental Approach to Transformative Learning,” in J. Mezirow (ed.), Learning as Transformation (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000), 35–69.