RAY EVANS WAS A STANDOUT ATHLETE at the University of Kansas (KU), an institution that has produced its share of legends. After enrolling in 1941, Evans went on to become the only KU athlete to be named All-American in both basketball and football and the only one to have his jerseys retired in both sports. His feats garnered recruitment attention from both the New York Knicks and the Chicago Bears before he interrupted his college athletic pursuits to go to war in 1944. As a veteran, he returned to KU and led the Jayhawks to the Orange Bowl, and in 1948 he played a season of football with the Pittsburgh Steelers. Along the way, even the New York Yankees threw in an offer to play professional baseball, which Evans declined (Just 2017; SB Nation Rock Chalk Talk 2014).

Amid this wealth of recruitments came an invitation from a Mr. Bowersock, owner of a gas station in Newton, Kansas, a railroad town situated some 150 miles southwest of the university in Lawrence. Bowersock was one of many people at the time driven to contend for bragging rights in the local softball leagues and tournaments that were ubiquitous in the postwar United States. In August 1947, before Evans’s final football season at KU, the Knights of Columbus in Newton hosted a softball tournament, and through some means of persuasion, Bowersock brought in the college star Evans, now remembered as one of the best all-around athletes ever to play for KU, to pitch for his sponsored team, Sox Super Service.

Though softball has evolved into several forms, the game that was all the rage nationwide in the postwar era was what is now known as fastpitch. Played on a scaled-down diamond as compared to baseball, the game revolved around pitchers throwing underhand, often as hard as they could, while the batting team scrambled for hits, bunts, and steals to advance around the bases. It was a far cry from the relaxed “slowpitch” version of softball that is a widespread recreation today. Games could easily become duels between pitchers, as each batting team vied for unlikely contact with the ball and a defensive slip that would allow a run to break the impasse. Final scores of 1–0 or 2–1 were not uncommon. In the first game of the tournament, Sox Super Service met a team known in the Newton city league as the “Mexican Catholics.” Like Evans, many of the Mexican players were veterans, except when they went to war, they had interrupted not their studies but hard labor as track workers for the railroad. These were the second generation of traqueros (track workers) in Newton, whose parents had begun to settle there during the period of the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1920. One of those elders, Canuto Jaso, arrived in Newton in 1919 after a stay in El Paso, Texas, a staging point where many Mexican émigrés would meet the enganchistas (labor recruiters), who would then channel them to jobs around the Midwest (Innis-Jiménez 2014, 69). Jaso played baseball while in El Paso, and his children continued playing the family’s favored sport after settling in Kansas.

The Mexican traqueros in Newton first lived in boxcars and then in brick houses built by the railroad, forming a community known as El Ranchito. With relatively stable work and residence, some of the men formed a baseball team they called Cuauhtemoc and played in the Newton city league. In the late 1930s, the sons of some of the Cuauhtemoc players and their friends formed a team they called Los Rayos, challenging the older generation and beating them (Olais 2019). Players for Los Rayos were part of the “Mexican American generation”—U.S. citizens who went to war and, on their return, enthusiastically took to the game of fastpitch softball, which had enjoyed a surge of popularity around the United States in the 1940s.

The pitcher for the Mexican Catholics, Joaquín “Chuck” Estrada, had learned to pitch underhand while in the military. Numerous individuals whom I’ve interviewed in Newton repeated to me the almost legendary attribute that Chuck threw “without a glove,” suggesting a kind of naturalistic source of strength, or perhaps simply reflecting the confidence that his pitch would be so intimidating that fielding would not be necessary. Rey Gonzalez, who later played third base for Newton but was younger than the Rayos and served as a batboy in the 1947 tournament, recounted the game to me in an interview over sixty years later, about how the dueling pitchers retired batters one by one:

Ray Evans from KU came in to pitch for the Bowersock softball team. Had a good team, too. But anyway, they met—in the second round they met our guys. I think they were playing—yeah, Magees, yeah. And it was zip zip zip, too, it was zip zip zip all the way, until the sixth or the seventh inning. . . . I remember the game. They bunted and they got a hit—or no . . . yeah they hit to the shortstop, or the third baseman, a hard grounder and he bobbled it and let it get away from him, and a run scored, and we beat Ray Evans one to nothing! He was so damn mad at those guys.1

As the Evening Kansan Republican newspaper tells the story, Evans gave up no hits, but a fielding error allowed Lou Gomez to get on base. Gomez proceeded to steal second and advance to third on an out, ultimately scoring on a wild pitch. The newspaper sports page held that Evans versus Estrada was “the best pitching duel seen in many a moon in Newton” (“Pitched No-Hit Game and Lost” 1947).

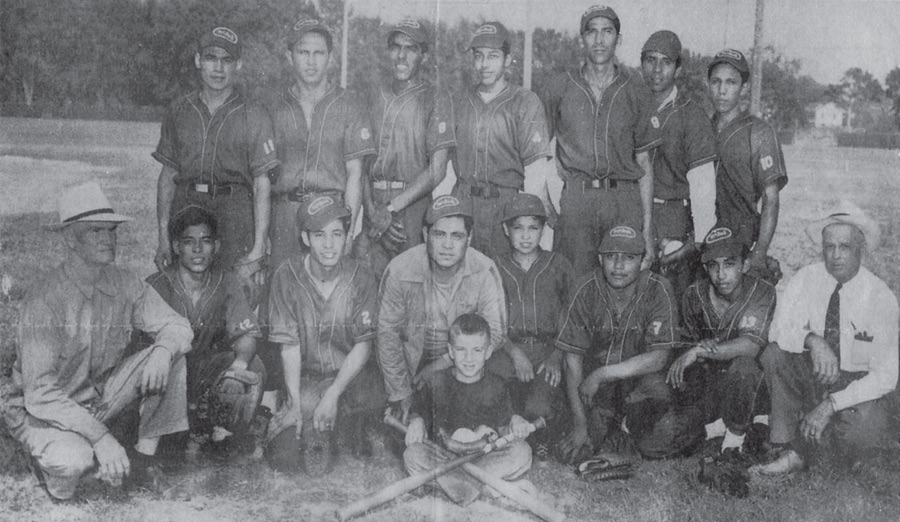

The story of the mighty Ray Evans pitching a no-hitter but losing in a softball game against an all-Mexican team doesn’t turn up in most accounts of his multisport exploits. But the feats of Chuck Estrada and the team that would pick up sponsorship in the next season from an Anglo potato chip merchant named Magee are retold from year to year (see Figure 1). Much later in Newton, these and other stories circulate in Athletic Park each year at the Mexican American softball tournament that the former Rayos players founded the year before the Evans-Estrada duel and won the year after. The tournament has run annually since then, celebrating its milestone seventieth year in 2018. For many of those years, the tournament director has been Manuel Jaso, one of many descendants of Canuto to play in the tournament.

This book is the result of an interactive engagement with softball tournaments and the people devoted to them. In my multi-sited ethnographic research, I followed the sport roughly between Kansas City and Houston. At over eighteen tournaments, in the homes of players, organizers, and umpires and in the neighborhoods where they played, I struck up conversations in the bleachers; listened to announcers, players, and fans in the heat of competition; browsed the archives of historical centers and memorabilia hounds; and recorded interviews with over fifty people. Through this fieldwork, I gained a sense of the importance of fastpitch in the ordinary annual life of certain Mexican American communities.

The portrait that emerges here is of people who have endured migration, limited economic opportunity, de facto segregation, and everyday racism, but also have gained a degree of social mobility over time, forming fastpitch teams rooted in friendships and family relations along the way. The particular appeal of fastpitch—what sport theorists call its illusio—draws people to the sport and moves them to invest time, energy, and identity into it. The resulting tradition links old-generation Mexican American communities in the Midwest, an area where they have more than one hundred years of history but little representation in scholarship, with the borderlands of Texas, the region that spawned a kind of scholarship that is the basis for this study: ethnographic inquiry into socially embedded cultural poetics.

A largely Mexican American crowd, clustered in lawn chairs under shade trees and pitched nylon canopies, or seated on aluminum bleachers in full July sun, carries on innumerable conversations while watching men play fastpitch on the red-dirt field. I catch a few snippets from my seat in the bleachers.

“Remember when we faced them in Kansas City? Twenty-one innings and then it was one to nothing. They didn’t have time limits in those days.”

Two women regale me with their stories of attending fastpitch tournaments in the railroad towns around Kansas, and then they situate their families within more widely known histories: “My grandfather, aunt, and uncle all rode with Pancho Villa. I have documentation.”

From the bleachers, a yell: “Come on, baby! Twist it!”

Rick Lopez, having driven over nine hours up from Texas, greets friends and former opponents. His T-shirt commemorates his team, the Baytown Hawks, for their unrivaled record winning “the Latin,” a fastpitch tournament that will take place two weeks later in Houston. That tournament is the second oldest to Newton’s, and it anchors a circuit of other competitions in Texas cities like Austin and San Antonio, just as Newton shares a summer season calendar with Kansas City and other railroad towns, including Topeka, Hutchinson, and Emporia.

Midmorning on Saturday of the tournament weekend, I run into Rey, known as “Chita,” behind the bleachers and he excitedly reports: “Did you see that game? A great game. A tough game. They should have squeezed him in on third with one out.” Then he is distracted, because a young man, just off the plane on a military furlough to make it to the tournament, asks if he can use a shower at Rey’s house.

“Okay, Mijito. I don’t think anyone’s there, but you know where the key is, right?”

From the other side, a woman, maybe in her thirties, taps Rey on the shoulder to greet him as the press box PA kicks off a polka. Rey throws a grito and dances off with her across the dusty park ground.2

Scholars note that people of Mexican descent in the United States have held a ubiquitous and persistent interest in sport that until recently was not well represented in scholarship (Iber and Regalado 2006). This book follows one bright thread in the fabric of Mexican American sport, a continuing tradition of fastpitch softball played in communities throughout the central United States, from the High Plains to Texas. This ethnic sporting practice is maintained through annual tournaments mostly played by men, with Newton’s being the longest running (Figure 2). Through fastpitch teams and tournaments, Mexican Americans have practiced a version of cultural citizenship, defined by Renato Rosaldo as “the right to be different . . . with respect to the norms of the dominant national community, without compromising one’s right to belong” (Rosaldo 1994, 57). The challenge of cultural citizenship for Latina/os and other people of color, according to Rosaldo, is to achieve full integration and recognition in American society without allowing the historical erasure of their particular identity and experience.3

When the players and organizers of Mexican American softball tournaments take part in what was once the very mainstream of public recreation in the United States, they also assert the right to construct spaces of cultural difference, defined and performed on their own terms. Carrying on with fastpitch into the second or third generation of players even as interest in the sport among men in general has substantially declined in favor of the more relaxed slowpitch version of softball or other activities altogether, the historically Mexican American tournaments now function as reunions that allow people to maintain ties to their shared past in specific communities and keep up the strong social relationships that form around the sport. Recognizing fastpitch as a practice of cultural citizenship situates it within a history marked by migration, marginalization, organization, and struggle, through which Mexican Americans have navigated complex negotiations of cultural, national, and local identities. In the process, they found agency by developing rich cultural resources. This book counts sport as one of those resources.

Softball as a differentiated cultural space is evident at the Mexican American fastpitch tournament held every Fourth of July weekend in Newton for over seventy years. This tournament is not only the oldest of its kind still running, but the only one—to my knowledge and that of the organizers with whom I’ve spoken—that throughout my fieldwork remained a predominantly Mexican American event by rule. In general, players were required to have at least one parent of Mexican descent. A team could bring as many as three players who didn’t have this qualifying ancestry as long as they put no more than two on the field at a given time. Non-Mexican players were not permitted to pitch or catch.4 While maintaining the identity requirement makes the Newton tournament unique, other Mexican American communities in the Central United States have also hosted fastpitch tournaments from the mid-twentieth century, when softball was one of the most popular recreational activities nationwide, de facto segregation was a social norm, and many Mexican Americans who were a generation removed from migration both sought access to public space in everyday life and built their own institutions to avoid or challenge exclusion.

Softball teams—formed around relationships of family and friends, supported by community centers and business sponsors based in barrio neighborhoods, and playing on ball fields nestled into those neighborhoods—are examples of a kind of barrio institution that have survived as the history of their communities continues to unfold. In Kansas City and smaller towns like Newton, softball became a favored activity among the Mexican people whose parents had been recruited to railroad work in those areas around the turn of the twentieth century. In urban centers of San Antonio, Austin, and Houston, softball also took hold in enclave communities facing the daily struggles of segregation and containment that historians have described as “barrioization” (Villa 2000). Throughout this Central U.S. region, which itself has been shaped by an economy and infrastructure that reached across the national border, softball teams and tournaments carry on a vernacular sporting practice that devotees invariably describe as a tradition. Mexican American fastpitch is a tradition because the accumulated years of playing justify playing more. Participants speak of a duty to continue what their predecessors struggled to build. They also speak of the sport as their “culture”—a repertoire of practice marked with accents or shades of difference that embed this sport within the historical particularity of Mexican American experience.

In this multi-sited ethnography of vernacular sport, I argue that the tradition of annual fastpitch softball tournaments has been maintained over generations by Mexican American communities because the sport provides an opportunity to engage in socially approved recreational activity and, simultaneously, remake and perform identity in terms that make sense to participants and speak to their experience. This was critical during a history that saw Mexican Americans embrace many aspects of U.S. national identity while nonetheless having the legitimacy of their citizenship and belonging repeatedly called into question or undermined in practice. Citizenship may not seem to be directly at stake in recreational sports, but with the United States ascendant as a world power in the early midcentury, new energy animated a dominant, national culture that articulated strength and winning with Americanness. At the same time, Mexican American citizens were subject to a longer-standing colonial discourse aimed at keeping them in a subordinate position by figuring them as racially inferior and unworthy of the citizenship that they nonetheless legally held.

This colonial discourse, a feature of Anglo American modernity that traces back to military conflicts over territory in the nineteenth century, justified the segregation of Mexicans from public life, including public athletic activities, in a rhetorical double move. First, pseudoscientific ideas about racial types proposed that mestizos, presumed to have substantially indigenous genetic makeup, were not fit for athletic competition with or against Anglos. Then rationalizations followed that those excluded from opportunities to play modern sport didn’t even want to do so, an expression of innate, cultural qualities such as fatalism and a lack of ambition. Actual Mexican Americans exploded these racist stereotypes by not only struggling to get their chance on the playing fields of America, but excelling once they got there. Mexican American fastpitch is part of this history of winning a chance to play.

During men’s fastpitch league night at Shawnee Park in the Kansas City barrio of Armourdale, the Outlaws are getting ready to play. Though some appear to be Anglo, they are talking over plans for the Newton tournament as they gather around the bleachers to get ready for the next game. The players pull wadded-up baseball pants out of duffle bags and put them on over their athletic shorts. Baseball pants, tending to be white or light gray, are iconic in the sport that is their only purpose. These particular pants bear the streaked marks of sliding on red dirt base paths. Remarking on the dirt, one player tells a story about when he used to work out every night. He rewore the same sweaty clothes, and the stink would drive people away at the gym, giving him access to the machines. Those people, he says, were just there to look at themselves in the mirror.

Seeing the players dress for a new game in clothes marked by the efforts of the previous game reminds me of a couple of women I had sat near, behind home plate at another tournament, where I enjoyed their enthusiastic and highly informed cheers. Their running commentary gave the impression that they were also players, as they yelled encouragement and advice to one of the teams: “Get dirty, kid! You got to get dirty!” While being willing to get dirty is a key to success, part of the regular ritual of a game is tidying up. The umpire calls time to brush home plate clean, since it may be completely obscured by dust, and then smooths the loose dirt around it with careful sweeps of his foot. The approaching batter does the same, moving the loose dirt with a shoe and feeling the contours of the batter’s box. Over the course of a weekend with back-to-back games, the landscape of a field shifts. Pits start to hollow out where the batters stand, deeper than anyone can fill by brushing into it with their feet. Batters start to prop their feet against the inside walls of the pits, seeking leverage on uneven ground where they have to stand to reach the strike zone hovering over home plate. Fastpitch gets played on ground that is solid but malleable, and the playing field, which is only purely level in an ethical-imaginary way, takes its physical form from the actions that have already played out on it in game after game all weekend of a tournament. The dirt also marks the players, at least their uniforms, so that they carry smudges of the history of a game off the field when it is over, and sometimes they can still find it there on their clothes when they put them on to play again.5 The task of an ethnography is to draw near enough to let historical dirt make its marks on our scholarship and to carry the marks into our other discursive spaces.

Fastpitch participants repeatedly emphasized to me that the games, leagues, and tournaments that make up their sport are part of something bigger—a tradition. Retired postal worker and veteran catcher Hector “Cuate” Martinez Jr. (as a twin sharing a nickname, he is known as “Cuate the catcher”) made this point to me when describing the game that he grew up watching his father play in Houston and that turned Settegast Park in his neighborhood into a festive hub of activity. Over time, he realized that this had a history, embedded in direct, personal relationships. He said,

So when my dad tells me stories about these guys, it’s history because I didn’t know about it. You know, it’s not like—we didn’t have a newspaper to publish this stuff. Nobody knew this about that, this and that. You know, you had to hear from somebody. Like lore, you know? You had to hear, it was like folklore you know, you’re like . . . it’s history.

To approach Mexican American fastpitch along these lines as a lore, as a vernacular, I take instruction from a prior body of anthropological folklore studies of Mexican America, for which the figure of Américo Paredes is paradigmatic (Limón 2012). José E. Limón, a leading proponent and elaborator of the ethnographic approach that Paredes modeled, suggests that such work remains relatively marginalized by the failure of academia to recognize and appreciate the richness of knowledge that is emergent in lived experience. As Limón notes, the publication of Paredes’s landmark work, With a Pistol in His Hand in 1958 was overshadowed by the roughly contemporary English translations of a novel by Carlos Fuentes (1960) and essays by Octavio Paz (1961), which together “became a cultural window into things Mexican for American intellectuals, deflecting whatever attention might have been given to a folkloric study by a Mexican American from Texas” (Limón 2012, 86). Limón finds a similar disinterest in the vernacular in contemporary cultural studies, which tends to focus on what he calls “circumscribed textualities” (131), texts that enjoy the spectacular reach of mass mediation, a process that inevitably imposes distance from a vernacular mode of discourse, production, and exchange of cultural material, even as those exchanges may be the very material that is represented and mediated.

Giving the vernacular its due as a source of insight alongside published texts that carry the prestige of being mediated has been hampered by residual associations of the field of folklore with antiquity and potentially romantic notions of authenticity. Softball fits awkwardly into this framework, as a tradition that was clearly begun at a particular point in the modern past. A vernacular form of a modern sport can easily fall into the cracks between old, folkish things and other things that draw more water in the present by virtue of their capacity to attract mass attention or investment. Folklorist Roger Abrahams suggests that scholars might deflect outdated assumptions that folklore is concerned only with the olden and the golden by thinking of the vernacular as the “poetics of everyday life” (2005, 18). This intrigues those of us who understand the vernacular and the everyday to be scales on which history, politics, and culture happen in significant ways. But making this case for the everyday requires confronting possible assumptions of its triviality.

Indeed, the “triviality problem” is one that has hampered study not only of everyday life but of sports in general. Situating play as outside the important matters of work, business, politics, and other similar domains presents a challenge of legitimation for those arguing for sport as a valuable object of contemplation and analysis. As Paul Bowman (2019, 26) observes, musing on the possibility of “martial arts studies,” legitimation may come through numbers (as in the billions of people who view the World Cup final), money (as in the massive financial investments in the American National Football League or the college basketball Final Four), politics (as in the explosive reactions to symbolic stances taken by athletes such as Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe), and other avenues. To assert that vernacular sport, undertaken in urban centers and small towns by mostly nonprofessional athletes for crowds that may not outnumber the players, is interesting and important for scholarly consideration confronts the triviality problem on various levels simultaneously.

The question should be, Trivial for whom? Fastpitch was certainly not trivial to the players who rushed home from work to play in weeknight leagues or who devoted years, even decades, of their life to tournaments. I have pursued an ethnography of Mexican American fastpitch not because I thought it was the most important site from which to understand sport in general, although I argue at various points that it does offer unique insights. Rather, this project arises out of my commitment to understanding Mexican American cultural production and an ethnographic preference for the aspects of Mexican American life that are valued highly by their participants. Fastpitch is important enough to study because it is important to certain Mexican American communities, where I chose to work.

The ethnographic priority that I place on vernacular sport runs somewhat parallel, against the modern grain, with the commitment of fastpitch-playing communities to keep an older way of playing going. Pierre Bourdieu, one of a group of scholars invited to analyze and discuss global sport in the run-up to the Seoul Olympic Games (Besnier, Brownell, and Carter 2018, 9), mused on the gap between professional and amateur sport that emerged in modernity, observing that the development of sport as “a relatively autonomous field reserved for professionals comes with the dispossession of lay people, who are reduced little by little to the role of spectators” (Bourdieu 1988, 160). Comparing sport to dance, the anthropologist/sociologist characterizes such modernization as a distancing from folk forms and rituals, which leads to an increased emphasis on “the extrinsic aspects of practice, such as the result, the victory” rather than on the practice of sport itself (ibid.). Of course the actual players and their physical feats are still very much the point of modern sport. But when we distinguish between “big” and “small” sporting events, this scale is defined by extrinsic factors, such as the money invested in teams or leagues; the reach of broadcast media representation; and articulations of players, teams, and games as emblems of identity claimed by populations of varying size. While there is abundant evidence that mass-spectacle sports can be intensely meaningful for fans, the scale of such sports imposes social distance between players and spectators. The bulk of sport studies deals with some aspect of the “relatively autonomous field” of sport as a large-scale spectacle. Yet orders of magnitude more people play sport than will ever play for a mass audience. Thus, the scale of focus for this project is sport that exists primarily to play and to be enjoyed by an intimate audience that is not necessarily separated from players by a vast social gulf.

Modern sport in general also lends itself to record keeping, often with an aesthetic of precise representations, producing statistics, scores, championships, and halls of fame. This is particularly true of baseball and its derivative games, in which scoring a game can involve collecting and archiving voluminous details about every pitch and play, even details that do not necessarily decide the winner, such as hits and errors. This is one face of what sport produces: indelible marks on history, of clear-cut accomplishments. The box scores for city softball leagues in the 1940s in Newton, Kansas, created a kind of unofficial archive by listing the players and key statistics. Thus, in a newspaper that might usually offer little clue whatsoever that there was a substantial Mexican population in this Kansas town, a softball roster entirely full of Spanish surnames is an intriguing historical wrinkle, adding we were here to the narrative reproduced annually in public parks: we still are.

Some of the devotees of fastpitch would appreciate efforts to deliver more precise facts and data in order to substantiate this historical presence, such as one interviewee who began our conversation by declaring, “Statistics! That’s the key!” But beyond sport as a mechanism for producing scores, results, champions, and records, there is the game itself as something that gets played, watched, remembered, and debated. As an ethnographer, my attention is more drawn to people’s ongoing reconstructions of memory and personal collections, some more orderly and comprehensive and some haphazard. In this way, I open my account to be shaped and informed by the voices and practices of participants in rich ways. In the time and place of playing, sport can produce a space that is a “palimpsest dense with meanings”—what Alex E. Chávez calls “moments,” formed out of “places, feelings, people thrown together” (2017, 297). This book comes with no promises for a comprehensive, “correct” account of everything that happened in the history of fastpitch, but using whatever historical, ethnographic, and other materials at my disposal, I aim to draw near to the moment of fastpitch, in Chávez’s sense.

Following these moments in the path Paredes laid, I approach fastpitch as an idiom of festive, culturally productive events, embedded in the social history of the Mexican American communities that host them. That is, I consider the cultural poetics of fastpitch. In his work on transnational music making in Mexican migrant life, Chávez calls for interactive, ethnographic engagement in order to “ground cultural forms in everyday life” (2017, 296). Like huapango arribeño, traditional string music from North-Central Mexico that Chávez follows with a transborder migrant community, the annual fastpitch tournaments rooted in Mexican American communities are a practiced version of what literary scholars have termed a “racial tradition” (53). Similarly, while this is a story on some level about sports in general, and about softball in general, it is always also a story of “our game,” of a specific tradition linked to specific histories. This is the scale of vernacular sport.

The vernacular refers to a certain scale of access, answerability, and social interaction. Once taken to mean “face to face,” vernacular marks relatively nonelite social spheres, where producers and consumers of cultural texts interact closely and in a marginal relation to capital markets—not always by choice. The event of an annual softball tournament may not be a literal everyday occurrence, but the relationships in which vernacular cultural production is embedded are produced and sustained over time through everyday life. Paredes’s ethnographic approach to corrido border ballads, verbal art and comparable “folk” forms, demonstrates that such vernacular cultural production is capable of being just as subtle, nuanced, and aesthetically sophisticated as more self-consciously creative work done by specialist artists, who may labor quite apart from their audiences until the work is “released.” Emergent forms may in fact present more complexity in their refraction of social experience. Because they have access, people take part in the vernacular whose lives have been shaped by social events and formations that might also have excluded them from “high” aesthetic and intellectual production. Vernacular cultural poetics are “answerable” in the sense that there is close proximity and rich exchange between people involved in the collective production of cultural forms. It is not a transmission across a firm boundary between producer and audience. On the vernacular scale, the circulation of discourse and affect in “democratically constructed and emergent, free-flowing performance” (Limón 2012, 104) often conforms to strict rules of convention, but also can appear unruly in terms of the shifting roles of producer and audience. I propose that the same can be said about vernacular forms of sport, which may include “lower” or more common degrees of athletic achievement, but more significantly, take place outside the large-scale intersection of money and media that frame sport as a mass spectacle.

An analysis of vernacular cultural poetics emphasizes culture as a process of making and social interaction that involves both subtle and spectacular acts of agency, as in the “artful use of language” that is the focus of performance-centered folkloristics (Bauman and Briggs 1990). As “enactments” (Abrahams 1977) carried out with the signifying resources of an established sport, the events that make up Mexican American fastpitch amount to acts of articulation. Much of the cultural work done at the tournaments that were the major sites of my field research is to articulate Mexican American identity to fastpitch softball. To articulate, in the sense proposed by Stuart Hall, is to forge “a linkage which is not necessary, determined, absolute, and essential for all times; it is not necessarily given in all cases as a law or a fact of life. It requires particular conditions of existence to appear at all, and so one has to ask, under what circumstance can a connection be forged or made” (Hall 2016, 121).

The conditions for this articulation are historical and particular. In fastpitch, Mexican Americans have articulated their identities to a sport that was at the very center of public attention across the United States in the 1940s. Over time it has become more marginal, at least as played by men. Yet the commitment of some ballplayers to the sport has been continuous through the specific histories of their local, barrio communities—histories that have featured exclusion, underestimation, dedication, organization, triumph, recognition, and other experiences along the way. This embeddedness in historical particularity is a characteristic of fastpitch as a practice of cultural politics (Figure 3). This is how a study of sport, like the study of other vernacular forms, can “take us to socially situated cultural practices as well as toward an understanding of such culture as intimately tied up with questions of domination, power, struggle, and resistance” (Limón 2012, 122).

Beyond asserting presence and continuity with a specific history, Mexican American fastpitch does not carry any obvious or consensual political position. U.S. patriotism is integral to many fastpitch events, fueled by the patriotic rituals of U.S. sport in general and the historical fact that fastpitch was popular and supported in the U.S. armed forces. But within the fastpitch scene, a wide range of political positions and outlooks is at home within the fastpitch scene. The importance of the multivoiced, emergent cultural swirl that goes on at the scale of the vernacular is heightened in an age when cultural performances like “Make American Great Again” mobilize power in the interest of a very precisely defined, imagined white national subject. The vernacular may not necessarily resist that political theater directly in content, but it does resist the vector of a purifying nationality in the way that vernacular practices tend to be open to multitudes and crisscrossing trajectories. As Chávez argues, the point of identifying and studying a racial tradition is not to solidify a “premodern, authentic specimen.”

Rather, the aim of this discussion is to identify how a performative practice, as part of a racial tradition, operates as part of and in response to the pressures and circumstances of modernity, how it is used to forge collectivity, how it changes and moves as people change and move, how it carries a different kind of power with it that is conceived against imposed and limiting notions of space and time. (Chávez 2017, 53)

By its form and process, cultural production on a vernacular scale resists purity.

Games are underway at Washington Park on the south side of Newton, one of three ball fields around town used during the Mexican American tournament. At this one, well into Saturday, a kid is taking a turn as announcer, holding a microphone. He calls the batters by first name over the PA system: “Up to bat is Louis, Roland on deck, Frankie in the hole.”

I wander across the street to the Girl Scouts’ “little house” that stands in an adjacent city park, where Kansas-style deep-fried flour tacos are for sale. The cool space inside offers respite from the heat, and people linger to reminisce. One woman from Wichita regales me with tales of traveling with teams to Kansas City, Salina, and other places: “I remember when they wouldn’t serve Mexicans, so we used to bring picnics.” Someone else mentions the football stadium beyond the outfield at Athletic Park across town—teams from Garden City used to sleep on cots under the bleachers and take meals there as well, prepared by women of the hosting community. I recall the conversation at a different tournament, in Kansas City, where the concession stand was behind third base and the old-timers gathered there to tell their stories while following the game. Back in the day, car-pooling teams on road trips tried to economize, opting when they could for all-you-can eat buffets. Food summons up stories as memorable as some of the games:

“That time in Hutch? They ran out of food.”

“My compadre could eat, boy.”

“It came from growing up rough. They used to get just tortillas, made the old way” [the speaker demonstrates by patting his hands and turning them one over another] “and one strip of bacon. So later on, he’d get two omelets and eat everything else, too!”

I had heard more stories elsewhere of eating and festivities around the tournaments. In Texas, an often-described image of the old days was the prevalence of barbecuing just past the outfield. In Houston’s Memorial Park, Field Number 1 has well-groomed grass in the outfield and a big green wall at the boundary fence like a miniature piece of Boston’s Fenway Park, so the mobile smokers are more likely to be set up in the parking lot. There are fewer of them now, old-timers tell me.

“You should have seen it at Settegast, back then,” more than one spectator tells me, referring to the city park in the heart of the barrio where the fastpitch tournament began. “The whole outfield was just lined with pits!”

I mention that fastpitch seems to be a sport where people tailgate for themselves, an idea that my hosts in Houston seem to like. They are David and Yvonne Rios, from San Antonio but regular attendees at tournaments around Texas, where the Rios’s family team, San Antonio Glowworm, competes. They open their circle of lawn chairs for me and a cooler of beer each time I come by. David begins to rave about his love of the sport. Even with most of his playing days behind him, he is devoted to spending weekends at tournaments. “I go back to work and people . . .” He begins to play out both parts of a dialogue scene:

“What did you do all weekend?”

“Softball, all day.”

“Whaaaaa?”

Breaking character, he turns to me. “But this is our life, papi! I love this! I love it!” He gestures expansively with his beer can and goes on to list all of the other spectacles or activities that he would rather skip to watch fastpitch—Fiesta, Sea World, and others. He smiles and shakes his head, both resigned and delighted by the strangeness of his commitment. Yvonne laughs at this too, commenting that it’s not everyone’s idea of a romantic couple’s weekend.

• • •

The festive atmosphere at softball tournaments—the food and drink, music, and storytelling—that accompanies the games situates fastpitch, like other vernacular practices, as a focal point of intensified sociality, standing apart from ordinary life as one of the “fundamentally social acts that stake claims of belonging through a vitality and conviviality otherwise severed or denied” (Chávez 2017, 53). The vitality that was ordinary in an earlier age of presumed segregation is one thing that fastpitch devotees told me about when I asked about the longevity of the tournaments. People started the Mexican tournaments in response to a continuum of overt and implied exclusions. Such grievances are not an ahistorical constant, though. Some things do change and have gotten better. But memories of the bad old days of segregation mix with a nostalgic desire for the sociality of neighborhoods and families that became close-knit partly because of the circumstances of enclosure and containment that structured everyday life. The paradox of achieving the social mobility to move up and out of barrio homes while nostalgically longing for the community experienced there is one of many cultural tensions that overlay a fastpitch tournament.

All of this is premised on multileveled, intensely felt, and publicly expressed forms of caring. Numerous scholars of sport and games focus in on this care—the attachments and attractions of a particular game that amount to a shared affect and investment in the idea that a sport is worth playing. This is the idea of illusio, introduced by Johan Huizinga (Garrigou 2008, 164). Anthropologist Robert Desjarlais glosses illusio as “the investment people make in the activities that give meaning to their lives, their commitment to them” (Desjarlais 2011, 12). This affective tie, which is obvious to those involved and devoted to a particular sphere of practice, can seem arbitrary or oblique to those outside it. Illusio drew Desjarlais’s ethnographic attention to chess in a project he calls an “anthropology of passion” (15). In his research on the game and its devotees, Desjarlais pursued questions such as, “Why devote one’s energies to a time-intensive pursuit that is little valued or understood in one’s own society?” (13).

In a society where sport is everywhere, it is not passion for sport itself that is remarkable. Rather, the specific activities and events that people choose to invest with passion indicate a particular illusio, which can also be understood as a genre in the performance of difference. This has been an important reason to resist treating softball, and the specific softball tradition that is my focus, as a subset of baseball. The legitimacy of softball—and fastpitch in particular—as a sport in its own right was expressed by many of the people I spoke with, and I endeavor to reproduce that priority here. That is not to say that the uniqueness of softball should be my main argument. An intriguing thread throughout this work that I must leave for another researcher to pick up is that the same communities that developed a fastpitch tradition, even the same individuals within those communities, played basketball under comparable circumstances and for similar stakes. Also, it would be foolish to deny the close relationship between softball and baseball outright. For some players, softball was a replacement sport after their prospects in competitive hardball had dried up. But I think it would be a misrepresentation to propose that everything I have observed and heard about fastpitch could just as easily be found in any other sport. The strong commitment that many participants maintained to their sport was to fastpitch in particular—“this game we love,” as it is frequently called in social media posts—and taking that seriously in analysis requires considering the specific appeal and character of that sport.6

A runner is on first base with no outs, and a bunt is tactically in order. I stand behind the chain-link backstop, next to David Rios, who has risen from his folding chair in the shade to come closer and watch the action develop. He nods toward the runner, who is pressing his toe cleats on the leading edge of the base, crouching like a sprinter in the blocks. “You see what they should do?” David asks me.

In softball, base runners may not lead off from a base as they do in baseball, but stealing is allowed as soon as the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand. With the path to each base only two-thirds the distance of baseball’s ninety feet, a quick runner does not need much time to improve the team’s offensive position.

I give my best, rudimentary assessment. “Move him over.”

“That’s right. Bunt and move him over, Papa.”

It looks as if the fielding team concurs, and as the pitcher winds up, both the third and first basemen creep in close to the plate, gloves up. By the time the batter squares off and lowers the bat to a horizontal plane to meet the ball, the space he could be hitting into is excruciatingly tight. The pitch breaks upward, though, and he misses, for a strike. The batter steps out of the box to release tension, taking a practice swing, fixing his helmet, pounding dirt from his cleats. Returning to his stance, it looks as if he might have changed the plan, waving the bat over his shoulder. Just as the pitcher leaps forward and releases, the runner takes off. Swinging hard, the batter drives the ball to near center field. The outfielders sprint for it, but the runner is already rounding second. The shortstop covers third base with his teammates shouting where to throw: “Three! Three! Three!” The throw comes in toward third as the runner slides, raising a billow of dust, and the umpire makes his best calculation of vectors, speed, and timing with limited visibility: safe.

My ethnographic approach seeks to draw close to the distinct meanings that converge in fastpitch: the illusio of sports both particular and general; the social determinants of a game and a tradition and their effects that spill over the boundaries of play; and the practices of narration, representation, and memory through which people actively produce Mexican American fastpitch. Any ethnography is necessarily an act of translation between discourses and their characteristic lexicons and genres, if not necessarily between discrete, standard languages. To account for this, I need to situate my use of two key terms throughout this book, since trying to remain close to their use in the field potentially introduces some tension or dissonance with their significance academically. One, community, is a risky but sometimes necessary term for referring to collective subjects who make fastpitch happen. The other is the term of identity, Mexican, which I use in various ways and in combination with other terms, most notably in unresolved tension with American. I have endeavored to follow the lead of my interlocutors in how I understand and deploy these terms, but that is not to say that everyone I conversed with in this project would make the same choices. The language in this book is ultimately my responsibility.

I have already made reference numerous times to the “communities” involved in fastpitch, the collective form of the protagonists of this story. Critics who have unpacked its potential to romanticize and smooth over actual heterogeneity and boundary work within groups of people make a strong case that the meaning of community and its use should not be taken for granted (Joseph 2002). In this book, community refers not to the large-scale political entity that Benedict Anderson influentially described in characterizing the modern nation, though the people I interacted with in fieldwork are most likely all engaged in some fashion with the “deep, horizontal comradeship” articulated to the United States by nationalism (Anderson 1983, 7). But that is not the reference here. Instead, when I refer to communities, I am drawing on the sense from linguistic anthropology of a “community of practice” (Mendoza-Denton 2008, 230), a group of participants who take part in a shared repertoire of expressive acts and meanings. In this sense, one could speak of a “fastpitch community,” as people sometimes do, though more often the cluster of translocal relationships that develop among people involved in their sport is invoked as the “fastpitch family.” Community in this account also serves another important purpose of identifying local, often barrio-based groups of individuals and families, the milieu in which specific fastpitch teams and tournaments developed. These communities are people brought together by the labor needs of specific industries, the shared conditions of segregated residence and limited access to public institutions, a shared ambivalence with regard to the broader imagined community of the United States, and both felt and ascribed cultural attachments to Mexico. All of these shared circumstances of living amount to a common historical experience that is by no means uniform among all the individuals involved. But a substantial number of people can identify that experience as a reference point of difference from the experiences and circumstances of others, notably white Anglos.

The late Nuyorican scholar Juan Flores, in an essay critically considering the prospect of a generalized Latina/o identity, makes some useful points about community. Working subtly with Marxian notions of class, Flores elegantly deconstructs the Spanish term comunidad to consider what different referents might exist for terms of identity (1997a). Somewhat ironically, since in this project I tend to avoid the generalization of “Latino” or “Latinx” except when it is used in the source material, I find Flores’s analysis compelling as a schema for understanding specifically located communities that are discernible in actually existing, expressive practice. This analysis begins with the delineation of two qualities embedded in the term comunidad: común and unidad. Común speaks to the shared conditions that bind a community—that which certain people have in common. Among the specific local groups that I routinely describe as “softball-playing communities,” I use the idea of común to refer to the circumstances of living, defined by migration in the first decades of the twentieth century (by the relatives of many of the people involved) and by the subsequent circumstances in which they secured housing, interacted with markets of exchange and leisure activities in public, sought education, and so on. Navigating the specific contours of Mexican life in the United States, in a particular place and time, gave people experiences in common, making them a kind of community in itself.

But this is different from a community for itself. Flores goes on to argue that not every historical grouping that forms in such a way is characterized by unidad, a shared purpose or interest expressed in coordinated or concerted action. The consciousness or feeling of solidarity between people who share certain conditions in común can lead to unidad, though this is not automatic. To be sure, contrasting and contradictory ideas of a community for itself also makes the existence and outlines of “community” deeply contingent. The question of whether softball, or recreational sports more generally, was an activity and cause to which people should form a unified commitment did not always produce a consensus in the communities I’m talking about. The competing draws of different sports and activities or different associations—playground teams; school teams; a continuum of public, religious, civic, and professional organizations—and different ideas of what was in the interest of “the community” fed a diversity of positions about the relative value of fastpitch to the larger community and the relative significance of playing softball as a practice of community.

All of this heterogeneity needs to resonate in any reference made to “the community,” but such considerations also highlight a specific characteristic of sport that helps explain its prominence in communities where, because they are defined to some degree as distinct from society at large, the question of how and whether to draw together in unity carries particular stakes for collective survival and well-being. The relevant characteristic of team sports is they are exercises or rehearsals of unidad. This is partly what has driven other writers to try to articulate the collective benefits of participating in sport—those that extend beyond the obvious aim of winning particular contests. Often the terms available to describe these benefits are examples of human capital, characteristics that develop out of the shared experience of competition and organized unity of a team—such as leadership, pride, and confidence. José Alamillo situates these benefits as collective in his historiographic discussion of the role of baseball in the lives of lemon pickers in California, mentioning that the experience of sport cultivated forms of social organization and personal qualities that would later be applied in more direct social advocacy (2008, 100). Besides the personal development that players take away from participating in sport, they also practice solidarity.

The solidarity of a team is a project of unidad driven initially by the simplified and arbitrary illusio of a game, the shared desire to score points and win. The pleasure of this provides motivation, and the structure of the game determines how much the aim of winning is served by collective agency. Games can be turned by the heroic efforts of exceptional individuals, but when a team manages to unify players’ perception, thought, and effort—as in a swiftly and smoothly coordinated double play—the group momentarily acts as a collective subject, and it can stage a palpable drama of unidad above and beyond the obvious and apparent strengths that individuals hold. The unidad of a sports team is not at all immune from the exclusions that can occur in the forming of any collectivity, even in a “community-based” form. But as will be clear in some of the accounts that ballplayers have shared with me, with all its limits, the solidarity built through competition can endure beyond the game.

In interviews, at moments when it seemed that my interlocutors were thinking about representation, they used a range of terms to identify themselves collectively, including Mexican American, Latino, Chicano, Hispanic, mexicano, and American of Mexican descent. The dilemmas of naming have been a persistent feature of Mexican American identity, linking the representations of self and community to material effects of racial categorization in law, citizenship, and everyday life. Ethnographically, the priority of this project is to learn and respect the ways that people identify themselves. In less carefully chosen references, outside of an interview or when the focus is not on naming itself but on the utilitarian task of describing people, it was almost universal in my fieldwork for people to refer to themselves as “Mexicans” and their communities and collective projects as Mexican people, Mexican teams, and Mexican tournaments. These were variously juxtaposed against “Anglos,” “white teams,” “bolillos,” and “mainstream” sports, not at all in equal proportions.

I have adopted this use of “Mexican” to refer to a historically precise but analytically complicated mixture of race, national origin, cultural practice, and kinship. Somewhat in the vein of how W. E. B. DuBois wrote about race, “Mexican” became a badge representing a particular historical experience when used in the way that people did in my chosen field sites. For this reason, I demur on using the term “ethnic Mexicans,” which some colleagues have adopted in a well-reasoned effort at precision (Fernandez 2016; Barraclough 2019). Like “social class,” “ethnic Mexicans” sounds redundant in the context of my fieldwork, perhaps catering too much to a definition from outside the speaking community I am representing. At fastpitch tournaments. it was only necessary to qualify “Mexican” as “ethnic” if you began with the assumption that the former term denotes national citizenship. I did not find that to be taken for granted in the fastpitch world. In my prior work in some of these communities, I did hear references to “Mexican Mexicans,” the emphasis implying that when the aim was to refer to nationality, it must be qualified. I defer to many interlocutors who, in my estimation, implied that that it is identity as a lived experience that is fundamental and the identity granted by state documents is secondary.

But this book is also a hybrid document and intentionally made up of a crossing of discourses. In passages where I deploy the analytical registers of my profession, I follow Limón to refer to “Mexican Americans” (1994). The term captures the specificity of the experiences of most of the people I talked to in and around fastpitch. The absence of a hyphen is intentional and important, reflecting that the hybridity of “Mexican American” is not a synthesis but an open dialectic that is lived in tension more readily than it is settled philosophically (see also Bretón 2019). Other analytical frames deployed by my colleagues—for example, sports historians who refer to people of the “Spanish-speaking Americas” (Burgos 2007, 11)—trace important interactions and scales of identity that reach into globalized professional baseball. This transnationalism is also evidence in parts of the Mexican American fastpitch world. During fieldwork, I saw Mexican (Mexican-Mexican), Argentine, Dominican, Cuban, Venezuelan, and Guatemalan players make their appearances at traditionally Mexican American tournaments, usually as sponsored guest pitchers. But while certain pan–Latin American factors, including language, made these visits possible, such hemispheric networks existed in tension with deeply rooted local histories of Mexican American fastpitch. I have focused for this project on the latter.

The ethnoracial character of the tournaments that define these projects is based primarily in relations and networks that developed over time in direct interaction—neighborhood, family, work, and the sport itself. Though Mexican American is a usable term to capture the heterogeneous and historically shifting social positions of many people involved in the sport I am looking at, I do not mean to disavow Chicana/o. This project, and my analysis, would not be possible without the intellectual history of Chicana/o studies and the social movements that animated it. Moreover, in the field, I recall at least one nostalgic conversation in the bleachers when a fan mentioned “when we were Chicanos” favorably. Movement poet and professor Ramón Del Castillo confirms this overlapping history in his poem “Kansas Fastpitch Softball a la Chicanada” (Santillán et al. 2018). But that term, emphasizing political consciousness and autonomy claims, was generally not as salient in my fieldwork during the 2010s. Finally, no one I spoke to in fieldwork used or offered an opinion on the use of Latinx, though the scene could certainly benefit as much as any other from the interrogation of gender binaries embedded in the history of that term.

The chapters that follow take up different lines of inquiry in order to draw close to the experience of Mexican American fastpitch. Chapter 1 elaborates on the historical frame I am suggesting for fastpitch as a chapter in a long saga of Mexican people’s contested belonging in the United States. The longer histories within which Mexican American fastpitch emerged include the expansion of the United States by military conquest and the attendant racialization of Mexicans for purposes of governing. They also include over a century of Mexicans making their home in the center of what is now the United States, including Kansas, and effectively creating the region I call mid-América, through travel and interaction with the southern borderlands, mainly Texas. I note the emergence of Mexican American fastpitch in temporal proximity to famous moments in Mexican American political mobilization for civil rights and equality, the Mendez, et al. v. Westminster civil rights case, and the so-called Longoria affair. I also emphasize that athletic clubs and tournament-hosting organizations are part of a continuum of vernacular organizations through which people have negotiated questions of belonging and identity under these historical circumstances.

Chapter 2 focuses on softball as a national pastime in the early twentieth-century United States and identifies the segregated everyday life of barrio communities as the ground from which Mexican American fastpitch teams and tournaments emerged. Recognizing how fastpitch is deeply embedded in social relationships is key to understanding the enduring interest and commitment to sports in general and fastpitch in particular that are evident in Mexican mid-América. Within that social base, I suggest that softball provided Mexican American communities with a source of both competition and camaraderie.

Chapter 3 digs into specific tournaments, the teams that hosted them, and playing fields to render the processes by which Mexican American communities built a racial tradition of sport. As they did, they negotiated a shifting balance between tournaments as counter-public, barrio institutions, invested in particular people and relationships, and as a staging ground for those interested in presenting their athletic feats and capabilities to a broader audience and field of competition. Throughout the unfinished history of Mexican American fastpitch tournaments, the relative merits and limitations of remaining identified as a “Mexican tournament” as opposed to “opening up” in different ways remain unsettled and debatable, even as the boundaries established under segregation crumble and fade. This remains true for the identity of tournaments across changing circumstances, as well as for the people personally and collectively invested in them.

Chapter 4 examines the figure of the ballplayer, a privileged form of subjectivity that playing fastpitch produced in barrio communities. I note that sport as a kind of discipline of self-making provided Mexican Americans with a resource to counter racist constructions of Mexicanness. Part of what made the prospect of being a ballplayer a path of prestige was that it offered a means of performing generally valorized and legible versions of masculinity. This process produced local legends who distinguished themselves on the field. But many former players maintain that a more important outcome was the camaraderie among ballplayers and their communities, fostering enduring relationships that were ultimately more valuable than victory in a game.

Chapter 5 further develops the implications of the fact that modern sport is profoundly and assertively gendered, and softball itself in particularly complicated ways. Recognizing that fastpitch has been celebrated as a Mexican American tradition mostly as an activity of men, I highlight some of the women who also have participated in this tradition and claim it as theirs. As the position of softball in the gender-divided field of sport has changed over the past century, I argue that the social base of Mexican American fastpitch has made it a resource that endures across generations.

Chapter 6 analyzes softball as a cultural form articulated to Mexican American experience. In conversation with other scholars who have examined sport as a symbolic or narrative idiom, I consider the narratives specific to softball and baseball in terms of what appeal they might hold in a Mexican American context. These include enactments of individual-collective relationships and varying scales of opportunity that are part of the formal structure of the game. Considering how these narrative forms read against the ongoing political dynamics of Mexican identity in the United States sets the form of softball in a particular relation to the larger social formation. On this basis, I argue that a sport that might seem to play an ideological role to support unequal social relations functions differently for Mexican Americans, for whom the demarcated space of the playing field takes on utopian meanings in ways that contrast with social life.

The conclusion returns to the framework of cultural citizenship and the view expressed by people involved in Mexican American fastpitch that their sport of choice is “culture,” according to a sense of the term that emphasizes legitimate difference from a mainstream national identity. This discussion underscores the importance of fastpitch to Mexican Americans, arguing further that it is not a naive or even untheorized relationship. Rather, the illusio, or particular and perhaps seemingly peculiar appeal of fastpitch to its devotees, is embedded in the ongoing dynamics of Mexican American history and experience. Indeed, playing the game and maintaining a particular tradition of doing so are ways of materializing and recognizing people’s relation to that history.7

At Newton, it is the Friday night before the Fourth of July and the old-timers’ game is getting underway to open the weekend of the Mexican American tournament. Elder men who are veterans of decades of softball have divided into teams, sporting T-shirts printed for the occasion. All read across the back: “Hecho in America con Mexican parts. [Made in America with Mexican parts]” Paul Vega steps to the pitching rubber, his silver mustache seemingly qualifying him for the retirees’ game. His delivery also has a temporal connotation: he swings his arm back in a slingshot style not often seen these days, changing the direction of the ball when it is behind him to bring it forward again and deliver the pitch.

Stiff knees and short breath notwithstanding, the old-timers play a couple of innings, clearly enjoying their return to the red dirt diamond. Jocular shouts are a constant accompaniment as players cluster around the chain-link fence separating each team’s bench from the playing field. A foul ball crashes into the fence, just missing a man who has wandered out to watch the play from beside first base. “Watch it!” yells a player from the other side. “I don’t think they make parts for that year-model anymore!”

The teams and tournaments that are the living embodiment of Mexican American fastpitch in mid-América formed under historical circumstances that continue to inform their complex designation and memory as “Mexican” events. Though the communities that launched the tradition of Mexican American fastpitch have seen many of their members move some distance away geographically or socially, the games draw people to return to the ball fields that are layered with sedimented meaning. They come back for the relationships formed around playing and to reestablish or shore up their connections to specific origins and experiences in the past. Fastpitch softball is one way—for a substantial number of people an exciting, aesthetically pleasing way—to exist within Mexican American history, and indeed to continue to make it.

1. This study draws from a wide range of field materials. The source material includes my experiences at fastpitch tournaments, recordings I made during interviews, and my handwritten notes.

2. Grito is a stylized, emotional shout that is part of Mexican performance tradition, interjecting joy or affirmation, often in response to music.

3. As an ethnographer, my practice is generally to use people’s own names for themselves. My aim is to do the same with referenced material, using the terms of identity chosen by the author whose work I cite. Intervening in the politics surrounding Latina/o, Latinx, Latine, and other collective terms is not the priority of this project.

4. In the 2020 tournament, the long-time director, Manuel Jaso, was replaced in this role by Todd Zenner, who has played in the tournament for some twenty-five years. Zenner kept the identity rule with one expansion: predominantly Native American teams could now compete as well. In the first year with this rule, three Native teams competed, with one of them, Big Eagle Express, taking first place.

5. My thoughts on dirt are indebted to Steven Marston’s dissertation on dirt-track auto racing in Kansas (2016, 119), part of which tracks working-class and gendered articulations of dirt with authenticity and agency in vernacular sport. One participant in that study observes, “Dirt’s alive. So, it changes.”

6. Recent ethnographies focused on different sports that take up a similar dynamic of asserting identities otherwise marginalized in national contexts include Michael Robidoux’s Stickhandling through the Margins (2012) on Native hockey in Canada, Stanley Thangaraj’s Desi Hoops Dreams (2015) on South Asian American pickup basketball, and Nicole Willms’s When Women Rule the Court (2017) on Japanese American basketball. As I will discuss, studies focusing on vernacular spaces and practices of sport differ from the bulk of sport studies, which tend to focus more on professional or international sites, instances of sport that are self-evidently significant because of the scale and numbers of money, people, or fame involved. The work of Allen Klein, particularly in Baseball on the Border (1997), is notable as a rare ethnographic and transnational approach to baseball, and I share some of the key interests pursued in that essential work.

7. For historically oppressed communities, maintaining a racial tradition is a logical response to erasure. I certainly build on the invaluable work of historians who have sought to contest this erasure. Excellent published historical work has been done on Mexican American sport with a focus on a specific community (Alamillo 2003), a specific team (I. García 2014), or even a specific player (Iber 2016), each situated within broader histories of the relationships of Mexican American communities to athletic ambition and opportunity.