This is a story about a vast and serious epidemic afflicting the developed world increasingly over the last few centuries, one that has gone virtually unrecognized. Jaws is about its origins, how it was discovered, and what we can do about it. The epidemic’s roots lie in cultural shifts in important daily actions we seldom think about; we just do them automatically. We don’t think about chewing, breathing, growing, or sleeping, or even the position of our jaws when we’re not eating or talking. Most of these actions we don’t acquire as habits, that is, by doing them repeatedly; they are inborn. A newborn exposed to air starts to breathe and cry. A baby presented with a nipple opens her mouth, starts to suckle, and after a bit may reward you with a grin. In the evening, after driving you nuts with screaming, your baby sleeps like a log, no training required.

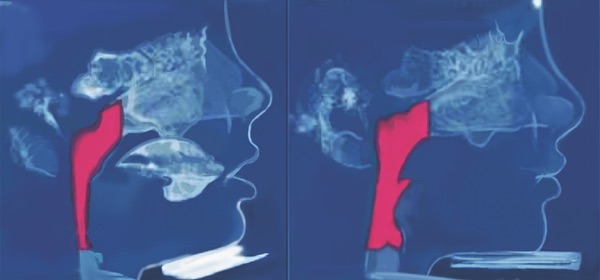

Simple and normal actions, yes. But, we argue, if repeatedly done in certain ways, early in life especially, over time they can undermine your health and alter your appearance in some surprising ways. If you keep your jaws apart and breathe through your mouth rather than through your nose for a few days, bite your tongue once in a while, or have insomnia for a few nights, you are going to be just fine. On the other hand, if you from an early age develop the habits of perpetually mouth breathing, eating mostly soft foods that require little chewing, and sleeping restlessly, snoring and squirming through every night, that could lead to distorted development of your jaws, face, and airway (the passage through which air enters and leaves the lungs) and to serious health problems later on—even to an early death. You would be a victim of a growing epidemic.

Modern industrialized societies are plagued by small jaws and crowded, ill-aligned teeth, a condition that the dental profession refers to as “malocclusion” (literally “bad bite”). Malocclusion is often accompanied by mouth breathing. Together, not to mention their negative effects on appearance, the two tend to reduce our quality of life and make us more susceptible to disease. And they are increasingly common. William Proffit, author of the most widely used textbook in orthodontics, the part of dentistry focused on straightening crooked teeth, pointed out the scale of the epidemic in the United States in 1998: “Survey data reveals that about a fifth of the population has significant malocclusion, and irregularity in the incisors (crowding of the front teeth) is severe enough in 15% that both social acceptability and function could be affected. Well over half have at least some degree of orthodontic treatment need.”1 A study of people in Sweden in 2007 showed that about a third of the population was in “real need” of orthodontic treatment and almost two-thirds has real or “borderline” need.2 Orthodontist and clinical director of the London School of Facial Orthotropics, Dr. Michael Mew, asserts that 95 percent of modern humans have deviations in dental alignment; 30+ percent are recommended to have orthodontic treatment (half have extractions); and 50 percent have wisdom teeth removed.3 If industrialized societies are plagued by jaw problems, might it not be smart to consider what changes might be made in those societies to ameliorate the problems?

The focus of almost all orthodontic practitioners today is crooked teeth, the straightening of which is the bread and butter of the orthodontic trade. But it may be that most orthodontists are concerned with the least of the jaw-related problems. Crooked teeth, other than their impact on appearance, are virtually harmless. Crooked teeth are, however, a signal of a more basic problem, poor development of the jaws. And distorted jaws influence more vital functions. For example, more than 10 percent of children may now have jaw-related potentially dangerous interrupted breathing at night;4 in one study in an urban area of Brazil, 55 percent of 23,596 children aged 3 to 9 years were mouth breathers.5 Although there has not been a coordinated effort to systematically gather data on the frequency of malocclusion, mouth breathing, sleep disturbance and the like, wherever they are examined they turn out to be common. Consider: if just 10 percent of the people in the United States were in bed with the flu, all the mass media would be focused on the “flu epidemic.”

By now you may be asking yourself, “Who are these people telling me there is a vast public health epidemic that is being ignored? Who is claiming that a long-admired profession may not be paying enough attention to a serious problem in its area of specialization? Who has the chutzpah to proclaim a need to dramatically change some basic aspects of industrial society?” Is this a standard “eat a pound of radishes a day and live a decade longer while enjoying a better sex life” kind of book? Actually, it isn’t. It is the result of a collaboration between two concerned scientists with very different backgrounds and experiences—a highly experienced dental practitioner and a world-recognized environmental scientist and expert in human evolution. And we are not selling any product or service.6

So how did these two scientists decide to write a book about this unrecognized epidemic? It started as a dinner club; Sandra and Paul and our respective partners, David and Anne, would meet for dinner in Palo Alto at one of several quality establishments every few weeks. The goal was to enjoy some good wine, good food, and good conversation about nature conservation, about how the world was a mess, and to wonder whether it was too far gone to save. It was during these dinners that Sandra started recounting to Paul and Anne a personal journey in her profession as an orthodontist. It was such a striking story, and of so much interest to Paul, that it culminated in his suggesting that they should write a book about it together. Sandra couldn’t believe that someone as published as Paul (with more than 50 books and 1,000 articles to his credit) would be interested in her work, but it was exactly her work that he found so interesting, the fact that something so life changing and dangerous was literally right under our noses and we didn’t see it. Paul had written a book or two on the same sort of life-changing issues, such as reproduction and racism, but this would be the first one that looked at such an issue from the fresh viewpoint that Sandra brought to the table.

Unlike Paul, who has three grandchildren, Sandra has two young children of her own. And as an orthodontist who had practiced the craft for 22 years, she discovered that she could not treat her own children the same way she was treating her other patients. She realized that, as in so many other professions, dental schools were pumping out students whose practices were “by the book” but were not necessarily best for patients. What she saw in practicing orthodontics the traditional way was that the solution to fixing smiles was usually to extract teeth, wire up the remaining teeth and use the resulting extra space to create beautiful smiles. And the results were exactly that and only that, beautiful smiles. But the smiles lacked “context.” These were smiles that in the process of building up a straight set of perfectly aligned pearly whites, left behind destruction to what could have been a strong jaw line, easy breathing, and a well-constructed face. Faces and health were left behind in the race to create that perfect movie-star smile.

So when Sandra was looking for the right way to treat her eldest child without extracting teeth, she first turned to “myofunctional therapy” as a rising and popular form of treatment. The idea was that how you chew, how you swallow, and how you position your tongue, repeated thousands of times a day for your entire life, would result in changes to your teeth and your smile. Imagine if every time you swallowed you pushed your teeth out a bit; eventually your teeth should move outward. Sandra enrolled her preteen children in myofunctional therapy and marched them through the exercises. At the same time, she kept studying the literature and investigating more intensely, while keeping a close eye on the kids’ development.

On a spring day in early 2012, at the recommendation of a colleague in an orthodontic myofunctional study group, she heard that one of the early founders of a practice called orthotropics, Dr. John Mew, would be giving a presentation in nearby Oakland. What she learned from Mew, the father of orthotropics, hit her with the clarity that must have first hit early scientists with the idea that Earth wasn’t the center of the universe. Surely it couldn’t be true, but so much indicated it was utterly true. Orthotropics finally explained to Sandra what she intuitively knew and what led her on her journey to find a better solution for treating her own children. While myofunction dealt with “muscle function,” orthotropics dealt with posture. While myofunction was concerned with the powerful movements we did from time to time, orthotropics dealt with what we did all the time. Sandra’s focus shifted more to posture, the resting state of the body, and by promoting the right oral posture she could finally address the cause and not the symptoms. So when Sandra started listing all the symptoms, Paul at first couldn’t believe that something so simple could cause such an epidemic. How could poor oral posture be a linchpin to so many diseases?

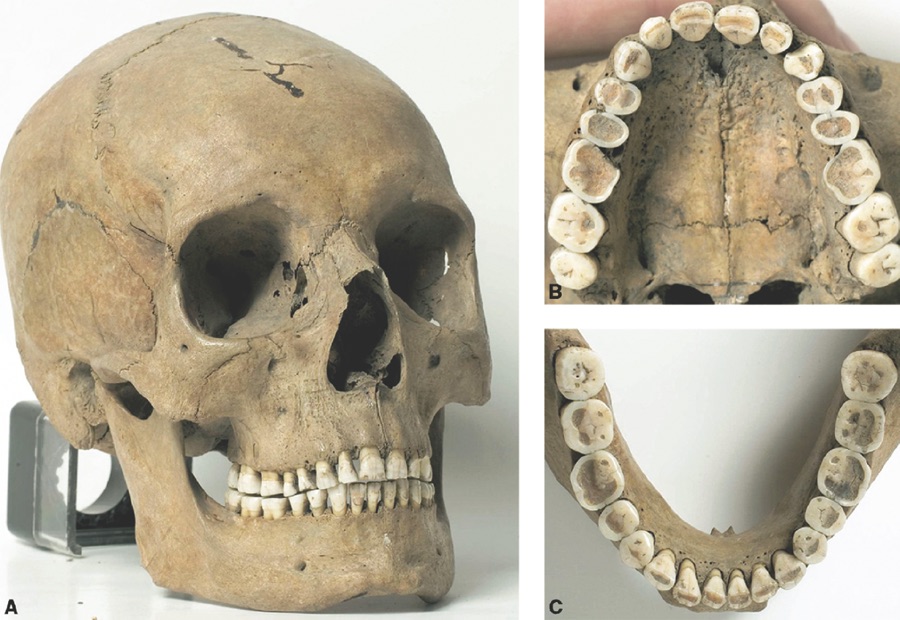

After several weeks of dinner club discussion, the importance of Sandra’s work became evident to Paul, as did how it fit into his long-term interest in human evolution and the environment. It even took Sandra a while to see why he was so excited about the connections among chewing, stuffy noses, and smiles. But he had spent his life connecting things such as population, food, toxins, resources, water, weather, war, and politics into a unified picture of the human future. When we finally took our idea for Jaws to an editor, he said, “Let me get this straight: no orthodontist is practicing this, you are the only ones who know about this, and you think that everyone needs to beware of a ‘huge public health issue’ right under their own noses?” Yes! The clincher for him, and many others, was Image 4, showing what a hunter-gatherer’s jaws look like, with roomy perfect arches of well-aligned teeth, with no impacted wisdom teeth—a movie star’s dream jaw, 15,000 years before movies!

It’s important to note that the two of us had no idea a jaw-based “epidemic” was happening until Sandra discovered its symptoms in her own children. Like the vast majority of people, even with our long-term scientific interests in public health, we had no awareness of an epidemic that could, alongside issues such as obesity and type II diabetes, be of substantial importance. The “jaws” epidemic was concealed behind the commonplace. Its most obvious symptoms are oral and facial: crooked teeth (and the accompanying very common use of braces), receding jaws, a smile that shows lots of gums, mouth breathing, and interrupted breathing during sleep. A bother, but hardly an “epidemic”—at least not until one recognizes that underlying these symptoms are frequently very serious diseases, many related to the stress of poor sleep. They include heart disease,7 eczema,8 lowered IQ, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and perhaps even Alzheimer’s disease.9 One important reason for the obscurity of the epidemic has been that evidence on the frequency and strength of the connection of those diseases to oral-facial issues often is quite difficult to obtain.

Usually health scientists depend on a statistical association, rather than clear knowledge of cause-and-effect mechanisms derived from experiments. For example, one seven-year investigation was done on middle-aged men in Sweden with sleep apnea—pauses in normal breathing when sleeping. Sleep apnea occurs when breathing during sleep is interrupted and the quality of sleep is impaired (during episodes the victim often moves from deep to shallow sleep). The afflicted men were found, when other likely causative factors are eliminated, to have more heart problems than those with uninterrupted sleep. In addition, effective treatment of the sleep apnea reduced the chances of cardiovascular problems.10 A similar Swedish study strongly suggested a causative connection of sleep apnea to coronary artery disease and stroke.11 Also suggestive, and frightening for those with sleep apnea, 46 percent of sudden deaths occurred between midnight and 6 am. In those without sleep apnea, only 21 percent of deaths occurred in that nighttime period.

The main kind of sleep apnea, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), is due to physical blocking of the airway. It seems to be increasing and has become a significant factor in public health. Some 20 percent of American adults are afflicted, and about 3 percent have a sufficiently serious case to cause daytime sleepiness. But sleepiness is the least of it. As many as half of cardiac patients suffer from the disease.12 Sleep apnea also appears to generate mental problems, including lowered IQ, shortened attention span, and difficulties with memory.13 Sleep apnea is often not diagnosed, and statistics have not often been gathered on its prevalence, age of onset, and presence in the medical histories of individuals who develop other various chronic diseases that may be related. Furthermore, evidence on mechanism, on, say, how interrupted breathing during sleep might make an individual more susceptible to a disease like Alzheimer’s, is frequently absent. These sorts of illness, as we’ll see, are what we’re concerned with in relation to poor development of the jaws, and the impacts of that developmental deficit on the face and the airway. But gathering more detailed information will be slow and difficult. Experiments won’t be used. No doctor is going to interrupt the breathing of large samples of people for a long period and compare their fates to “control” individuals not subject to nightly strangulation. You may be able to guess why not! Similarly, we would not suggest subjecting children to practices that we believe cause malocclusion to test our own theories about the jaws epidemic.

Escalating attempts to straighten teeth, to treat one of the epidemic’s most prominent symptoms, are one obvious indicator of the scale of the epidemic. Having braces as a child has become so common in the Western world that it can seem a rite of passage. Today an estimated 50 to 70 percent of children in the United States will wear braces sometime between the ages of 6 and 18.14 It is not clear how much the increase in use of braces in recent years is a response to a great explosion of malocclusion or a consequence of less expensive tooth-straightening appliances, better marketing by dentists, and changes in attitudes on appearance in a photo-addicted society (think “selfies.”). Ironically, the effects of braces may not always be as beneficial as people have been led to think. As we’ll see, braces may actually reduce the size of the airway,15 leading eventually to problems in breathing like sleep apnea.

That the diseases just noted are related to modern civilization is strongly indicated by the near absence of their symptoms in the evolutionary and historical record. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors had spacious jaws, with a continuous smoothly curved arch of teeth in each jaw, including third molars (“wisdom teeth”) at the back ends of the arches. Indeed, Stanford evolutionist Richard Klein, a top expert on our species’ fossil record, has told us that he personally had never seen an early human skull with crooked teeth. Further, the oral-facial epidemic of modern times, although rooted, we believe, in the agricultural revolution, was very slow in starting. Recently a cemetery of common people of the Amarna culture of ancient Egypt, dating to more than 3,000 years ago, was discovered. The skeletons had the tooth wear characteristic of farming peoples, the investigators noted,

Except for the occasional slight incisor crowding and rotation, observation of the teeth indicated that they were well-aligned with very-good-to excellent occlusion, in general. Thorough analysis of dental data from the Amarna burials has shown that Egyptian and most ancient teeth have extensive tooth wear on occlusal (chewing) surfaces of even the youngest individuals. Malocclusion is rare in Amarna but very common in America; tooth wear is extensive in Amarna yet rare in America.16

There is a common and serious misapprehension about malocclusion. As one friend said, “We take it for granted that malocclusion is genetic—we’ve always considered my son got his crooked teeth from my wife.” As you will see, virtually all the evidence shows that the oral-facial epidemic can be traced not to our genes but to changes in our culture, particularly to ones in how and what we eat and where we live. These have changed greatly from those of the Stone Age, in complex patterns starting around the time people began to settle down and practice agriculture.17 As anthropologist Clark Larsen put it: “There has been a dramatic reduction in the size of the face and jaws wherever humans have made the transition from foraging to farming.”18

With proper attention to our children’s diet, eating habits, breathing patterns, and what we term “oral posture” (how they hold their jaws when not eating or speaking) many aspects of the epidemic could be ameliorated or avoided entirely. Jaws could return to their hunter-gatherer and Amarna patterns of growth. There’s much that alert parents can do for their children and some things also that adults can do for themselves that can help to at least reduce the likelihood of some diseases like heart attacks and cancers.19 An array of evidence indicates childrens’ future well-being can be greatly enhanced by encouraging a few simple habits early in life. Consider how you yourself breathe, chew, and position your mouth when not speaking or eating. Being aware of that can add up to better habits that might positively change your life, improve your health, perhaps make you more attractive and successful, and transform how you feel about yourself. The key is first to develop awareness of those jaw-related habits that may eventually cause dramatic changes for the worse and then understand what can be done to kick those habits and create a better future for your family and yourself. That is the goal of this book. In it we will lay out the evidence indicating that an industrial lifestyle explains the epidemic of oral-facial health problems20 and discuss what remedies can be found. The views expressed here are not typical of the dental and orthodontic mainstream, but we feel these somewhat heterodox ideas need to get a hearing.

There is some history for the minority view we present, especially in the work of pioneering orthodontist John Mew, to whom Sandra took her son after hearing his lecture in 2012. Mew successfully treats patients by returning distorted oral-facial growth to its normal course through “orthotropics,” a program that encourages normal jaw growth and development. Orthotropics is a very important discipline with a lousy name. It is too easily confused with standard “orthodontics,” from which it has major differences. As a result Sandra renamed “orthotropics,” calling it “forwardontics,” to avoid the confusion. The two names are synonymous. Forwardontics is the term we will use from now on, except when we refer to Mew’s work or to literature that employs the designation orthotropics. Forwardontics is more descriptive for the general public and includes all treatments that focus on forward development of teeth and jaws in both children and adults.

The problems of modern jaw-face-airway development were uncovered through the work of a series of dedicated scientists and practitioners, including Mew, observing dramatic changes over time in facial structure and in the incidence of chronic diseases, checking them against evidence in different historical periods and in different cultures, conducting animal experiments, drawing on general knowledge of human genetics and development, arriving at reasoned conclusions based on that wide array of evidence, and applying what they have learned. This has given scientists greater understanding of the oral-facial health epidemic and the changes required to end it. But in this case there has been little attempt to bring these complex results to the general public as an integrated story—something we hope to accomplish with Jaws.

The bottom line of our narrative is that your health and happiness, and more likely that of your children, may be at risk due to habits to which most of us never give a second thought. So here are some of the key questions you could be asking yourself:

How we eat can be just as important as what we eat. How we breathe can be just as important as what’s in the air we breathe. How we sleep can be just as important as how long we sleep. These are all aspects of oral-facial health.

Are these dire warnings already starting to sound like diet alarms you’ve read before? Foods you were told to avoid yesterday, only to find that the warnings were passing fads, that “further research” reversed the advice? Fat is good for you, fat is bad for you, fat is now good for you again. Coffee is good for you, then bad, now good. Gluten is bad, vitamin E is good, and so on. As you read Jaws, the information and advice might sound familiarly “diet-y.” But Jaws is not just offering faddish advice. True, some of the information in Jaws has been around for a long time., simple advice that may start to sound like your mother telling you to “eat with your mouth closed,” “sit up straight,” and “chew your food.” Well, Mom was onto something; she didn’t realize that what she was asking for was not just about manners and being polite; it was one dimension of forestalling a trend that has now become a public health problem. The oral-facial epidemic has developed over centuries, but it has accelerated as a result of common practices associated with our highly industrialized Western civilization that, since World War II, has taken over the world. So, not surprisingly, you won’t find any one-step solution in Jaws, but rather a more sophisticated overview of a complex problem with suggestions on how to prevent and treat it—and a challenge to think.

It is often said that the face is the window to the soul, but it is also a window on the health status of the person behind the face. The human face provides visible signals that could indicate serious underlying health problems. Not only can problems in oral-facial health be an indicator of problems in the rest of your body, but they can also be a determinant of how good you look. The habits that can make faces unattractive in our culture are, sadly, the habits that can make bodies unhealthy.

Overall, then, an unheralded change has been taking place in our society. We are altering our faces with surgery and braces and other technological means when the real changes we need to make are modifications in how we ordinarily breathe and eat and sleep. They can have a more significant and lasting improvement on the quality of our looks and our health than a plastic surgeon’s talents. Using quick fixes to solve our health problems and adjust our smiles may in some cases actually lead to additional problems in the long term.

Jaws starts with a chapter describing the transition from healthy Stone Age jaws to often sickly modern ones—an example of cultural evolution (change in the nongenetic information groups possess). It deals with the longstanding “nature–nurture” question, as it applies to oral-facial change. Chapter 2 focuses mostly on chewing but dips into other factors like allergies tied to the oral-facial epidemic. Chapter 3 looks at the significance of what we chew, how we chew, and where we chew (in a house or in a forest). Chapter 4 tells how attractiveness ties into jaw health. Chapter 5 discusses how and why changes occur in human jaws, faces, and oral posture. Chapter 6 brings mouth breathing and its ills to the center. Then in Chapter 7 we go to the personal level and indicate things you and your family can do to keep the epidemic at bay. In Chapter 8 we discuss how to recognize the effects of the epidemic, and we give an overview of where you might find help from dental professionals. In Chapter 9 we expand our view to ask what changes in society’s culture can be made to help people like you deal with the epidemic.

Throughout the book, as scientists we naturally refer to the scientific literature describing jaw development, cultural practices, various eating/breathing environments, and related health and appearance issues. As is often the case when natural science and social science are considered together, this literature remains, sadly, rather fragmentary. In part this is because there are important ethical restrictions on making controlled observations or (especially, as suggested with sleep apnea) doing experiments on our fellow human beings. There also are logistic and, in particular, funding constraints on conducting “prospective” studies, those in which subjects are selected in advance and then followed through time. Prospective studies are the gold standard of research on health in human populations. Getting hundreds of subjects to accept the inconvenience of behaving in a certain manner (such as eating a special diet for long periods), keeping careful records, and being repeatedly interviewed, is neither easy nor cheap. Prospective studies require lots of money and patience, with periodic follow-ups that may go on for years.

Thus most studies are of the less revealing, but easier and much less costly, backward-looking type known as “retrospective”—for example, asking adults about their eating habits when they were young and then comparing the present state of health of groups who, say, were vegan or who loved steaks growing up. Such studies can yield a lot of useful information, but they have some inherent limitations. For instance, how accurate are the memories? Could the responses be biased by people reporting what they think the interviewer wants to hear? If the same questions had been worded differently, would the answers have been different?

Forwardontic (orthotropic) research, investigating the techniques used by John Mew and his colleagues, faces these problems and then some. Orthodontics is at least a clear-cut, professionalized, medical/dental treatment, engaging a large group of practitioners, and has thus been the subject of more or less standard medical research. Forwardontics is primarily a postural discipline, pursued by a small cadre of orthodontists and dentists. It is harder to practice than conventional orthodontics and less likely to be financially profitable, and its successes are highly dependent on patient cooperation. For those reasons forwardontics (as orthotropics) has been relatively ignored by the research community, and conclusions about forwardontics often need to be drawn from small samples, certain types of anecdotes, photographic histories of patients who sought help (not, then, a random sample of individuals), and the like.

Because of these limitations, some caveats should be mentioned. We are focusing on problems that seem to be related to oral-facial development in a rapidly industrialized world. Answers to some of the issues are relatively clear cut, for example that the modern environment in which children develop, especially how they chew, how they rest their mouths when not eating or talking, and the allergens to which they are exposed can greatly influence the development of their jaws, faces, and airways. It also seems likely that oral-facial responses to the relatively new industrial-era environment are largely responsible for increases in sleep apnea, which is known to be very stressful. In turn, stress notoriously contributes to an array of serious chronic diseases. But evidence of the scale of stress and of its contributions to those diseases or the mechanisms that make the connection is often thin to nonexistent.

In some cases we’ve simply speculated—we suspect that snoring in hunter-gatherer children was rare, for example, but we haven’t found evidence to support that notion—no reports from, say, people who lived with!Kung people on their sleeping habits, no evidence that leopards were attracted to snoring kids during humanity’s long trek out of Africa. Considering the relationship of snoring to modern jaw configuration, mouth breathing, and similar factors,21 we thought it likely that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were not heavy snorers. In any case, we’ve tried to make clear, at least by context, when we are simply speculating, and our reasons for doing so.

In short, Jaws is designed to introduce you to the vast problems of oral-facial health, which, like issues of gluten, might have once seemed as simple and insignificant as sliced bread and which now are as significant as sliced bread. And it is designed to help you decide what, if any, personal actions you can take to improve your health and well-being. It’s a guide for thinkers, not a recipe book. So read on and make up your own mind.

1. W. Proffit, H. J. Fields, and L. Moray. 1998. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: Estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 13: 97–106.

2. E. Josefsson, K. Bjerklin, and R. Lindsten. 2007. Malocclusion frequency in Swedish and immigrant adolescents—influence of origin on orthodontic treatment need. The European Journal of Orthodontics 29: 79–87.

3. In his lecture “The melting face”; retrieved on February 20, 2016, from www.youtube.com/watch?v=NvoX_wEtwDk.

4. Guilleminault and R. Pelayo. 1998. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Annals of Medicine 30: 350–356.

5. R. A. Settipane. 1999. Complications of allergic rhinitis. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings: 209–213.

6. C. All royalties from Jaws will go to supporting work related to the subject of the book, making human lives better in a rapidly changing environment.

7. P. Gopalakrishnan and T. Tak. 2011. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Cardiology in Review 19: 279–290; M. Kohler, J. Pepperell, B. Casadei, S. Craig, N. Crosthwaite, J. Stradling, and R. Davies. 2008b. CPAP and measures of cardiovascular risk in males with OSAS. European Respiratory Journal 32: 1488–1496; H. K. Yaggi, J. Concato, W. N. Kernan, J. H. Lichtman, L. M. Brass, and V. Mohsenin. 2005. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. New England Journal of Medicine 353: 2034–2041.

8. J. I. Silverberg and P. Greenland. 2015. Eczema and cardiovascular risk factors in 2 US adult population studies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 135: 721–728. e726.

9. A. Qureshi, R. D. Ballard, and H. S. Nelson. 2003. Obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 112: 643–651 A. Sheiham. 2005. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83: 644–644; A. Sheiham and R. G. Watt. 2000. The common risk factor approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 28: 399–406; R. G. Watt and A. Sheiham. 2012. Integrating the common risk factor approach into a social determinants framework. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 40: 289–296; and Matthew Walker. 2017. Sleep the good sleep: The role of sleep in causing Alzheimer’s disease is undeniable; here’s how you can protect yourself. New Scientist October 14–20: 30–33.

10. Y. K. Peker, J. Hedner, J. Norum, H. Kraiczi, and J. Carlson. 2002. Increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged men with obstructive sleep apnea: A 7-year follow-up. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 166: 159–165.

11. Y. Peker, J. Carlson, and J. Hedner. 2006. Increased incidence of coronary artery disease in sleep apnoea: A long-term follow-up. European Respiratory Journal 28: 596–602.

12. A. Qureshi, R. D. Ballard, and H. S. Nelson. 2003. Obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 112: 643–651.

13. G. Andreou, F. Vlachos, and K. Makanikas. 2014. Effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea on cognitive functions: Evidence for a common nature. Sleep Disorders 2014.

14. Retrieved on February 2, 2016, from http://bit.ly/1OFUnjm.

15. Kirsi Pirilä-Parkkinen, Pertti Pirttiniemi, Peter Nieminen, Heikki Löppönen, Uolevi Tolonen, Ritva Uotila, and Jan Huggare. 1999. Cervical headgear therapy as a factor in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatric Dentistry 21: 39–45.

16. A.Gibbons. 2014. An evolutionary theory of dentistry. Science 336:973–975; J. C. Rose and R. D. Roblee. 2009. Origins of dental crowding and malocclusions: An anthropological perspective. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry 30: 292–300.

17. Ron Pinhasi, Vered Eshed, and N. von Cramon-Taubadel. 2015. Incongruity between affinity patterns based on mandibular and lower dental dimensions following the transition to agriculture in the Near East, Anatolia and Europe. PLoS ONE 10:e0117301. doi:0117310.0111371/.

18. C. S. Larsen. 2006. The agricultural revolution as environmental catastrophe: Implications for health and lifestyle in the Holocene. Quaternary International 150: 12–20.

19. Y. Chida, M. Hamer, J. Wardle, and A. Steptoe. 2008. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology 5: 466–475.

20. F. Silva and O. Dutra. 2010. Secular trend in malocclusions. Orthod Sci Pract 3: 159–164.

21. M. P. Villa, E. Bernkopf, J. Pagani, V. Broia, M. Montesano, and R. Ronchetti. 2002. Randomized controlled study of an oral jaw-positioning appliance for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children with malocclusion. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 165: 123–127.