MANY PROLOGUES have been written for Dubai. Some of these take place at the city’s khor, or creek: the marshy waterway that Arabs, Iranians, and South Asians made into a harbor. Others start in Haifa, Khartoum, Kochin, and Saigon. There are as many prologues as starting points for journeys to Dubai. And they can be infinitely rescripted to fit the themes at hand and to anticipate those to come. No prologue is an origin. Each is an epilogue for stories before its own. It’s where one chooses to begin, for now.

This prologue opens in London in 1959, because this is where many people licensed to change landscapes stood ready to change Dubai’s. It is toward the end of a summer of shimmering lawns and refreshing shade. Many recalled that summer being just warm enough that an iced drink sweat through a linen napkin. Benevolent sunlight merely added color and definition to gardens that appeared to care for themselves. Such manageable conditions can seem far away from a summer endured in Dubai, where the only reprieve from howling sands that can cut through skin and the hard, diamond-bright sun was the inside of an airless, aching souk.

The difference between the two worlds composed a common narrative—the first portrayed as pleasant and accommodating, the other as grueling and inadequate. The two settings were the stage for how ideas and modern things were dispatched from one world to improve the other—things like electric grids, asphalt roads, hospital care, and hotel lobbies. Architects had no major role in this narrative, not yet, but they were ready couriers of expertise, with calculations and measurements to rectify any apparent deficiency. They were trained to chart delivery, and therefore to guarantee it. Architecture though offers more than the assembly of itemized ingredients. On a landscape that had endured millennia without it, the building of reinforced-concrete architecture would declare urgency, its completion would announce arrival, and its advertisement, as a showpiece, would affirm that standards had been set, and met, and that more was on the way.

Cold drink in hand, the British architect John Harris was at a garden party that summer in London’s plush and verdant neighborhood around Campden Hill Square. It was the right place at the right time. He had just turned forty and ran a small architectural practice. He had a reputation for courtesy and composure. Mindful of others and alert to where he stood in a room, he spoke in “clipped, gentlemanly tones” and could sense “exactly which anecdotes and insights were going to convey his thoughts.”1 He could smoothly turn party chatter into a sales pitch. Procuring projects was his strength, but getting his practice off the ground had taken longer than expected. War service had interrupted his studies and sent him to Hong Kong. Then, when the British relinquished Hong Kong to Japanese forces in 1941, his “five most dreadful years” began as a prisoner of war. Detained in dilapidated military barracks, he stayed sane by creating watercolors with paints he somehow managed to come by. Medicines smuggled in saved him from dying from diphtheria, while he witnessed fellow prisoners die from diseases and random execution. Luck, he later asserted, was the reason he survived. Freed from the barracks but still trapped in a fiercely undernourished body, John Harris returned to London in 1946.2

As disorienting as his last five years had been, the next three were productive and deliberate. Once he regained his health, he matriculated again at London’s Architectural Association and secured his degree in 1949. He met his wife, fellow architect Jill Rowe, during their studies. In 1949 they opened their “one half of one room” office in their Marylebone home, but Britain’s postwar rebuilding did not provide them much work.3 Harris wanted to translate the trauma of his imprisonment into designing for “extreme” climates. The couple pursued commissions far away from Britain, in places endowed with the petroleum required by the recovering British economy. In 1951, the firm was hired to design a small “building research station” in Kuwait, thanks to a family connection. In 1953, the pair won an open design competition for a new hospital in Doha, a city expanding on Qatar’s petroleum profits. They delivered the hospital four years later as the surrounding region’s largest architectural project. Such an accomplishment should have led to an influx of clients. Instead, Harris learned that new work did not materialize on its own. That realization might have been on his mind at the garden party.

There, Harris met Donald Hawley, who at thirty-eight was Britain’s ranking official in Dubai. He was in London for holiday that he timed to escape Dubai’s most insufferable month. His position in Dubai was considered a “hardship post.” As the political agent for the Trucial States, Hawley embodied more than a century of British control over Dubai’s access to the outside world.4 As there was no higher-ranking official within a day’s travel, Hawley experienced for the first time being in charge, and it suited him. His mandate from the Foreign Office was to make the British policy in Dubai seem rational, clear, and benign to those both inside and outside the city. For a rising diplomat, social events like London garden parties led to work opportunities, and vice versa. He used his summer leave to find British “short-term expert aid” for what he called Dubai’s “prelude to serious development.”5 The garden party’s host, Hawley’s and Harris’s mutual contact, was also supplying experts: English-language teachers through the British Council for new planned schools. An architect or town planner was not on Hawley’s contact list, but Harris had the skills to convince him that one should be.

As a rule, Hawley kept to telling simple stories. He was paid to portray the British intercession in Dubai’s affairs as fair and constructive. Hawley later claimed he organized Harris’s initial visit to Dubai so that he would produce the city’s first town plan. The story may be told as matter-of-fact: Two men mindful of their respective careers forge a gentlemen’s agreement to shape the future of a place 5,500 kilometers away. In actuality, Hawley was not authorized to hire Harris, much less to mastermind an outright modernization program for Dubai. Instead he was instructed to choreograph the appearance of change without the British, or any other foreign entity for that matter, seeming to dictate it.

The two men’s encounter at the garden party was enmeshed in a history of British empire and colonialism. Their prologue did not supersede other prologues, but it had the political power to alter other ones for good. This chance meeting determining how one of the world’s most watched cities would take shape was based on more than a century of incidents, and indecision, that accumulated to define British control over Dubai. Before Hawley ever sought his London experts, Great Britain, as early as 1820, wielded military and political power to monitor Dubai’s trade and restrict its imports. In his history of Dubai and the region, Hawley noted that “there were no diplomatic representatives” from other countries, but he failed to point out that this lack was because the British government prohibited them.6 Dubai’s leaders could communicate with the outside world only through their British contacts; the city’s imports were officially limited to British products. As the naval ships had done previously, Hawley as the political agent restricted entrance of American, European, and Arab visitors but gave little thought to indigent arrivals from South Asia. By cordoning off the coast, British officials envisioned a place frozen in the nineteenth century. Both Hawley and Harris eventually would witness what happens when the cordon came down.

If defined as a centralized project delivered by authority, modernization began in Dubai when it was sanctioned to begin by the British Foreign Office. That had happened by the time the first political agent, Christopher Pirie-Gordon, moved to Dubai in 1954. Before then, “watch and cruise” British officers had been stationed aboard naval ships a couple of hours off Dubai’s coast.7 At first, Pirie-Gordon’s arrival did not amount to more than sporadic improvement projects like a mobile health clinic and water-drilling studies. These missions did not accumulate into a vision of a city. Dubai was rarely even referred to as a “city”—more of an unsteady node of nomadic Bedouins and fleeting boatmen.8 The arrival of the political agent was a calculated signal, an embodiment, of a modernization program. The agency framed modernization as an installation of bureaucratic legibility on a place where there had been none before. Modernization was not to be a splendid act of power but a managerial ordering, and, on that auspicious afternoon in London summer, Harris began working on what kind of role he could play in that endeavor.

FIGURE P.1 Dubai Creek from aboard an abra (small boat), November 1959. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

In reality, the keepers of Dubai’s port—Arab, South Asian, and Iranian traders—managed it on their own. They survived economically by exploiting the incompetency of British surveillance, thereby debunking any fictional notion of the port as a nineteenth-century relic. Dubai’s merchants were already making the city modern through covertly maintaining the city’s connections to the rest of the world. Mercantile persistence resulted in the city’s ascendancy as a regional hub for arms sales and more, to the frustration of British surveillance efforts. Modern appliances managed to arrive, as did news and ideas from other parts of the world. Traders heard about political changes happening nearby and how the larger world was responding to the collapsing forms of colonial dominance outside Dubai.

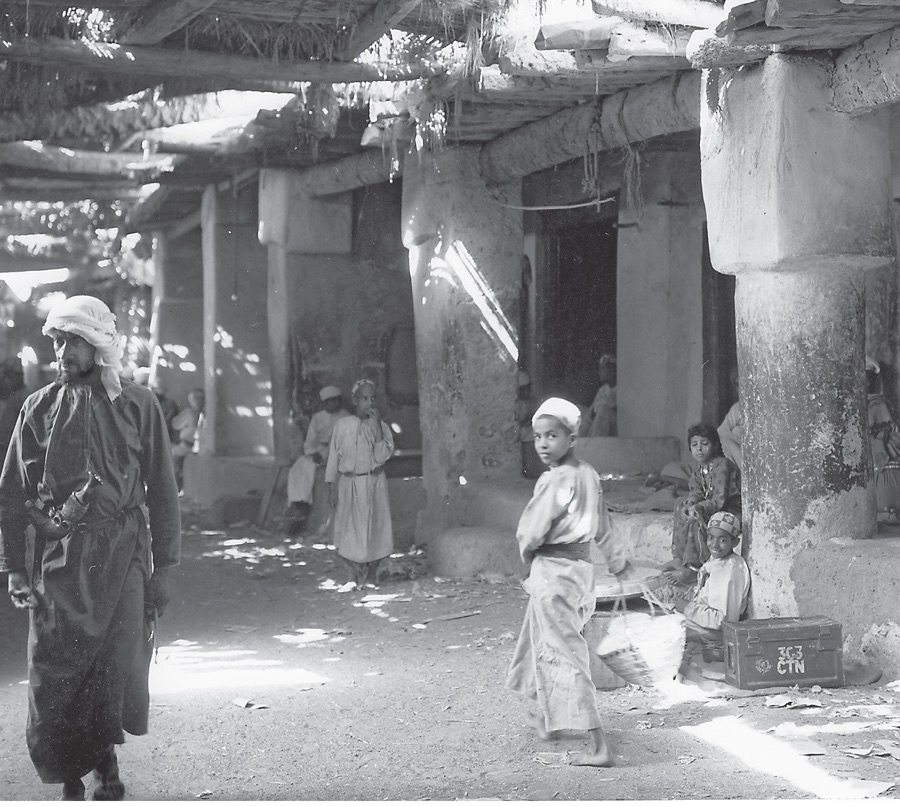

FIGURE P.2 Souk in Dubai, November 1959. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

In the 1950s, Dubai’s traders realized they could maintain connections with the world—as long as their onshore premises did not betray those connections. Wealth, therefore, was not revealed in improved port facilities or in the city’s built surfaces. The wealthiest of the merchants still expressed their stature in the coral houses made with Iranian craftsmanship and Indian hardwood. If manufactured building materials passed through the port, they were not intended for Dubai’s transformation; rather they were being re-exported to other places for the sake of profit.

Once stationed in Dubai, the political agent sought to supply more intelligence on just how successfully Dubai’s traders circumvented British inspection. Ostensibly there to manage and surveil Dubai, he was evaluated by how his actions advanced the British economy. In responding to this directive, the agent tried to arrange Dubai in a way commercially beneficial for British industries. He argued that the port’s resourcefulness and grit could serve a British advantage by establishing a “free port” from which British companies could secure, and profit from, the regional trade in petroleum.9 By running illegal trade rings counter to British decree, Dubai’s merchants had proved their usefulness to British interests. They were the agency’s evidence that the city had the potential to create a lively commercial hub, an easier and more profitable pursuit than keeping the port shut off.

A key figure in the hiring of John Harris also enjoyed some weeks of London’s memorable 1959 summer, but he wasn’t at the garden party: Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, Dubai’s ruler from 1958 until his death in 1990. Any telling of the Maktoum lineage of rulers usually culminates in Sheikh Rashid’s ascent as a business-savvy leader who only improved on the business formula of his predecessors. Maktoum rule is often portrayed as unhindered. More truthfully, economic and political forces frequently compelled Maktoum rulers to reconsider strategy in order to ensure Dubai’s endurance. In the years prior to becoming Dubai’s ruler, Sheikh Rashid faced the greatest challenges ever to his family’s claim to power. At the outset of his rule, the Foreign Office even doubted whether it could make good on its promise to protect his sovereignty.

The Foreign Office framed its inexact and irresolute modernization effort as a tutorial in leadership for Sheikh Rashid. Britain’s continuing protection was conditioned on his pursuing a financial and bureaucratic ordering of his urban dominion on their terms. At first his British contacts didn’t trust him, but within a couple of years of his ascent, Rashid was adorned with honorifics like the “merchant prince.” British experts found him “extremely charming.”10 Journalists and diplomats described him as an astute, imperturbable man with a wry smile, a pipe, and a recycled aspirin bottle filled with tobacco.

Accounts of the first years of Sheikh Rashid’s rule often read like a modernist legend: the ready-mix creation of a modern city out of a proverbial “fishing village.”11 According to legend, Sheikh Rashid achieved for Dubai in a couple of decades what took a century elsewhere. It has been often reported that in the first six years of his reign, Sheikh Rashid saved Dubai Creek from commercial demise, built a modern port, provided residents with running water, and launched electricity and telephone companies. In that time span, Dubai also secured street lamps, a modern hotel, and a landing strip for airplanes. Finally, the city could be seen from an airplane at night.

The 1960s and 1970s are called the Sheikh Rashid years, when Dubai’s ruler allegedly assembled this city. To tell the story as a conveyor belt fairytale is as deceptive as it is enticing. Modern comforts and the infrastructure that provide them are designed to seem simple. A town plan might express where these services could be situated, but any realization comes about through a combination of compromise and brinkmanship. Reconstructing these decades through another kind of built work, this book reveals the gambits, missteps, and bravado that added up to a city. To reassemble the Dubai of these decades pries open a two-pronged myth about Dubai: On one side is the falcon-winged tale of brave Bedouins and Arab merchants enduring desert and maritime hardships, and on the other is the extraordinary “rising from the sands” of glass-and-steel towers, amassing into a “futuristic city.”12 The two mythical states result in oversimplified praise (“Look at what they’ve done!”) and damnation (“What else would you expect?”).

Between the two extremes are bouts of toil, mistake, hesitation, and restart that generated today’s Dubai. As a result, the reality was in constant need of a rewrite. Dubai had to be revealed as a place where one could find work, where one could be born, where one could eat meat from the market without getting sick. Later it needed to be shown as a place where one’s bank accounts were secure, where airplanes could land safely, and where central air conditioning kept the city at a comfortable 72ºF. A physical city was constructed and so was the image of one. They were equally important.

Months after the garden party, Harris made a nine-day visit to Dubai, where he walked the city’s unpaved streets, witnessed the port halfway through an unprecedented engineering project, and met the city’s ruler. In May 1960, Harris presented Dubai’s first town plan. More than a plan, it was then the most accurate map of Dubai from which the city’s leaders and experts could chart Dubai’s growth and transformation. Hawley called it Dubai’s “basis for all future town planning.”13 The town plan presented Dubai as measurable and legible, and it supplied the instructions to guide future growth “along sound lines.” The plan proposed the trajectories of new roads and residential districts that reached out of the apparent disorder of existing Dubai into open areas designated for new development. Adhering to those lines, a phalanx of British consultants and salesmen would deliver a newly sanctioned modernization.

Harris was but one of the experts that the political agency brought to Dubai to promote the narrative of clarity embedded in a British-friendly modernization program. Large-scale infrastructure, eventually, was the preferred tactic. Focused on the agents who designed these projects, this book offers an introspective look at how a globalizing practice of architecture and urban development found its footing in the final years of British empire. Late British colonialism is often described as politically impotent, directionless, and disorganized. On the contrary, there was a “modified form of commercial empire” being formatted, a reformulation that emphasized establishing the British economy as a lucrative exporter to the rest of the world; it was not only an economic role but also a means to hold on to a “world-power role.”14

This economic-political stance required not only the exported goods but also the advisors and experts who ensured that the products were inserted into foreign lands. Beginning in the mid-1950s, British engineers introduced Dubai’s ruler to the political potential of infrastructure. What ensued was the quiet start of a significant project of twentieth-century architecture and planning: to make a world city out of a place that had been fenced off by British policy for more than a century. At first, Dubai offered a testing ground for receiving British design as an exportable commodity. By opening Dubai’s markets once again to global trade routes, however, Dubai could no longer be beholden only to British rule.

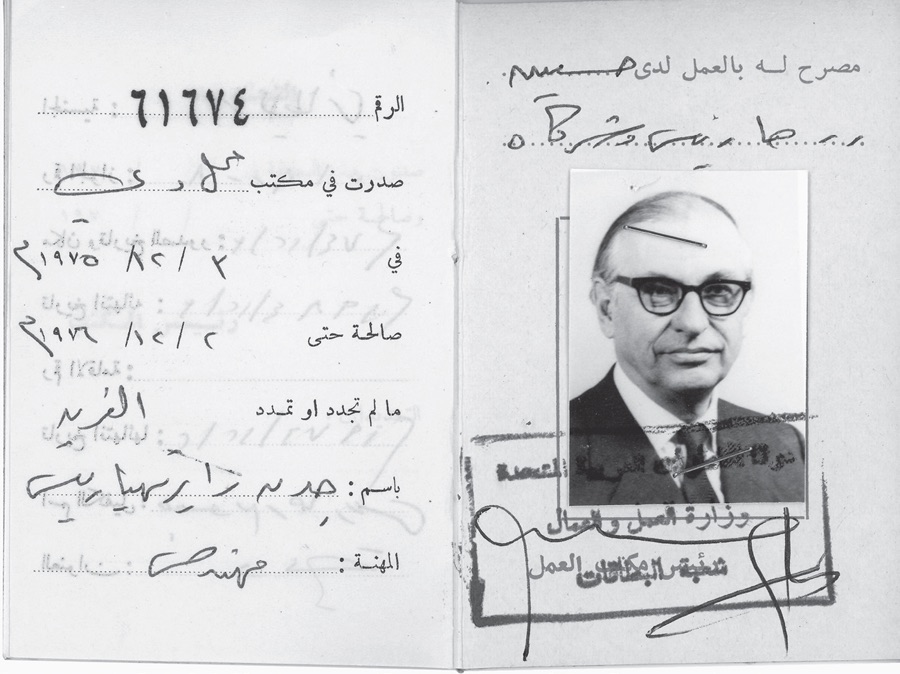

FIGURE P.3 Dubai work permit for John R. Harris. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Dubai’s future was its greatest asset, but no experts were showcasing fantastical visions. Instead, they exhibited prowess through a “quick calculation on the back of an envelope” and won contracts to produce the evidence that things were getting better.15 Until the late 1970s, borders, lines, words, coordinates—entirely invisible on Dubai’s landscape—assured prospective creditors, residents, and workers that Dubai had a future. They signaled what else was possible. The collateral the city could put up was the transformation already happening.

At this time, the presence of foreign experts was justified by an apparent absence of local expertise. Foreign consultants, however, delivered a more crucial element: the appearance that Dubai’s growth and expansion happened outside its politics. By being reduced to their financial transactions, engineers, designers, and administrative professionals were set outside Dubai’s social and political reality. Whether serving a military force or an engineering firm, many experts claimed that “the last thing on my mind was interfering in local politics.”16 As the anthropologist Ahmed Kanna has made clear, this “political ingenuousness” promised by so many experts continues to drive how Dubai markets itself today.17

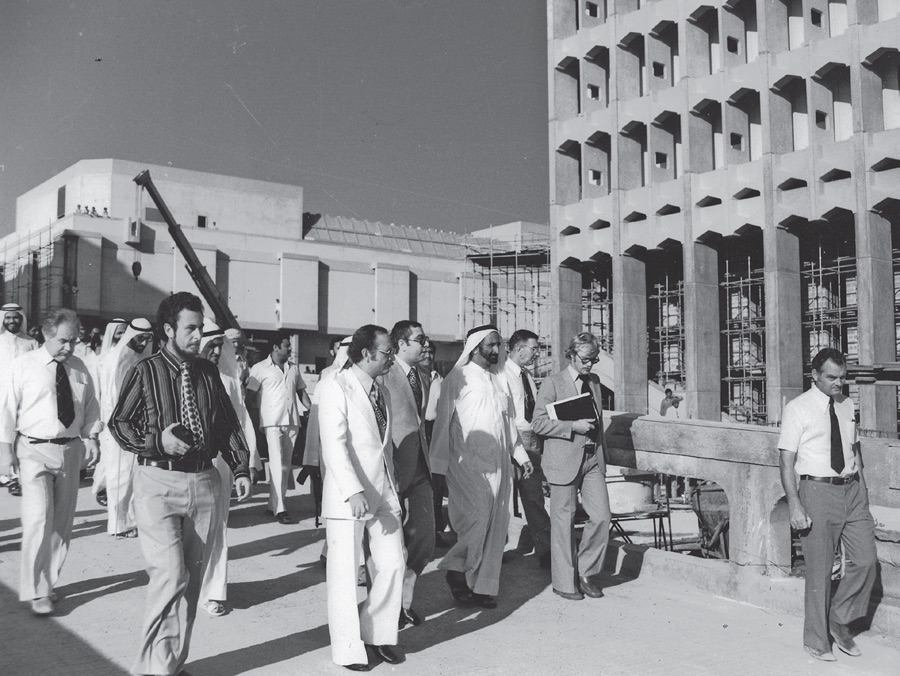

FIGURE P.4 Experts and advisors attend Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum (center) during a site visit to Dubai’s World Trade Centre, circa 1978. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

The hired experts—engineers, architects, contractors, and marketers—both built the city and composed a story about a sound investment. They even helped write Rashid’s own biography, cobbled together from handed-down anecdotes and quips recorded by newspapers and magazines. Those smitten by their own part in the telling of a city’s thrilling rise contributed to Dubai’s global image. Their stories of profitable successes in turn lured more of their professional ilk to the city. Maxims like “What’s good for the merchant is good for Dubai” were attributed to the ruler merely because countless businessmen swore they had heard him say it.

Even while these profit-minded advisors helped create the city’s infrastructure and modern institutions, they regaled journalists with stories of how Dubai was free of red tape and any stultifying bureaucracy. A handshake, they claimed, was as good as a contract. They took pleasure in describing how Rashid sealed their deals by drawing literal lines in the sand to mark a future construction site. Such stories, however, did not take into account what happened after the theatrics of deal-making in the desert: A Pakistani municipal worker promptly arrived and recorded the coordinates with British-sourced surveying equipment. This worker was evidence that Dubai was mapped and modern before it might have ever looked it. Just as much as they created Dubai’s mythology, experts also chipped away at it. Increasingly, the ruler relied on published contracts, ordinances, and merchant-bank loan agreements, all of them written up by hired experts. The more information that experts documented on paper, the more that could be read, and therefore scrutinized, by even more experts.

The experts proved to be excellent storytellers, but they concealed as much as they revealed. Rarely are their contracts, and even more rarely the correspondence around those contracts, found in public archives. We can still witness some of their commissions that altered Dubai’s landscapes—like bridges, buildings, and deepwater ports. Beyond the built environment, we can read trade magazines, promotional brochures, and newspaper advertisements for the tales contracted service providers spun for good copy. They praised their built projects to promote themselves and, in the process, praised Dubai. Brazenly self-promoting language, correlated with profit-driven motives, makes it obvious that these claims should not be taken at face value. Perhaps an exception among his contracted peers in Dubai, John Harris was eulogized by a former colleague as “a remarkable man in the sense that he was unremarkable. A master of the understated who went about his work quietly and yet with determination.”18 Subtler experts, like John Harris, were careful with what they shared, usually relying on rehearsed crowd-pleasing anecdotes. In the 1980s and 1990s, many more British firms were finally clued in that their future profits might lie in a region Harris knew well in the 1950s. He was often invited to speak at professional organizations and even at his alma mater, in the hope that he would divulge trade secrets. He rarely veered from his talking points.

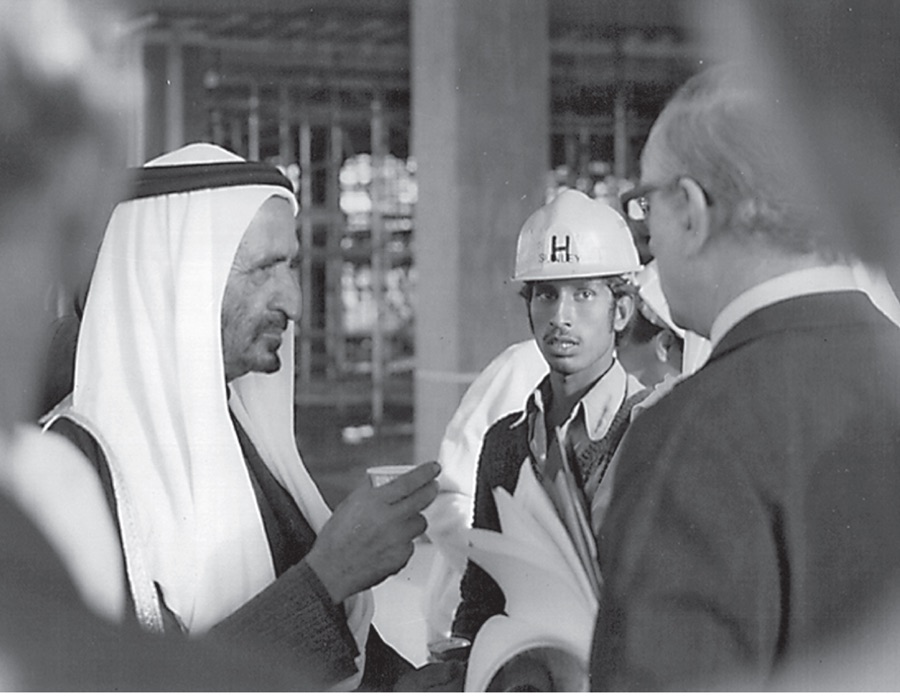

FIGURE P.5 Sheikh Rashid, a construction worker, and John Harris during a site visit to the World Trade Centre. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

Since the issuance of Harris’s town plan, millions have come to Dubai to execute it. The number of professional experts was dwarfed by the numbers of skilled and unskilled workers who arrived to realize and maintain the structures that Dubai’s leaders financed. In the early years of the British-endorsed modernization project, Dubai’s port was as open as its wall-less city to those who would come to build the projects. As late as the 1970s, almost anyone could land on shore in the pursuit of financial opportunity, if at their own peril. Without a reliance on formal recruitment networks, the message got out quickly that Dubai needed help in making something bigger than itself.

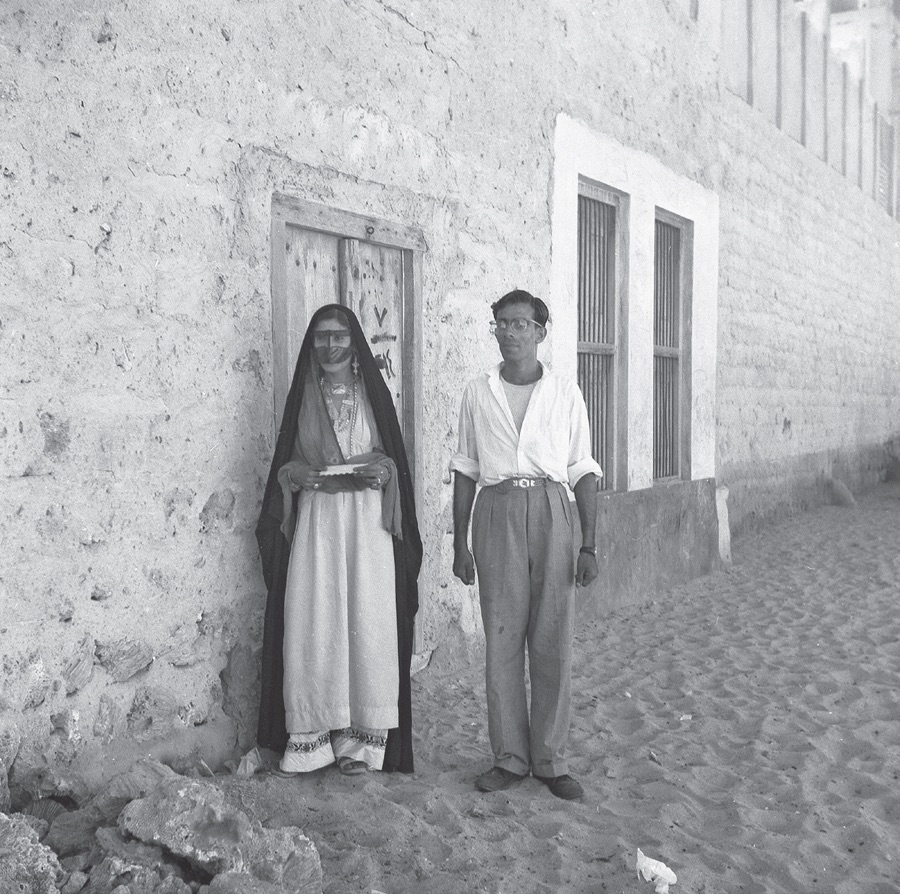

But unlike cities such as Bombay and Guangzhou, whose migrants largely hail from the rural areas of their respective countries, Dubai relied on transnational labor networks, many of which were already configured by a century of British imperialism. By the mid-1950s, foreigners made up the city’s majority. Each new plan, building project, and engineering feat heightened Dubai’s appeal to foreign workers. Every worker who came, sometimes despite life-threatening risk, had reason to believe this city of dusty construction sites and expanding horizons offered new chances and opportunities. Stories of previous workers were the prologues to their own stories.

FIGURE P.6 Two residents of Dubai, November 1959. Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

There is no publicly accessible archive in Dubai. Many documents should be at hand but are not to be found—for example, cadaster maps that Dubai’s municipality produced as a result of Harris’s town plan and the early decrees by which the municipality sought to maintain the city’s spatial ordering. Many who agreed to talk about this recent past rely on nostalgic memories and often do not want to say anything possibly construed as negative. Stories prefaced with “You can’t write this” are often not scandalous: It is understandable, for example, that a leader of a rapidly developing city being shaped by an evasive British presence, profit-hungry foreigners, and a delicate local power structure could occasionally lose his temper. What unfolds in trying to gather Dubai’s urban history is a complex and ambiguous field of hints, snapshots, and occasional documents. One might expect that modernization—specifically its capacity to calibrate and to record—would leave behind an archive. In fact, the outright rejection of posterity’s importance might have been a deliberate, and also modern, act. A constant cleanup of messy histories can lead to a city that suggests the modern ideal—self-willed, simple, and on-message.

That nearly every major development project in Dubai was completed without much attention to preserving a historical record can be interpreted to mean that there was no time to think of legacy. Sheikh Rashid’s name adorns the city’s feats of infrastructure, but aside from an unexceptional “eternal flame” commemorating Dubai’s oil discovery, monuments don’t have much of a role in the city. Rashid’s champions often portrayed him as too busy to be thinking of memorialization.

There was, however, an early and vigorous marketing effort—found on the pages of the London Times, the Financial Times, the Economist, and countless professional magazines—broadcasting Dubai’s stories of transformation. From the 1960s onward, Dubai’s government had a press machine, a team of storytellers for Arabic- and English-language audiences, to make sure the city appeared in print. These published pages, while not so much focused on redrafting the past, aimed to reset Dubai’s starting point to coincide with modernization. All the while, Dubai’s history was slipping away through the revolving door of consultants. One hazard of an inaccessible history lies in what happens when people eventually want to tell that history. As there is increasing interest (and money) to preserve and publish Dubai’s history, the voids are creating tempting opportunities to fill the blanks with comfortable fictions instead of awkward facts.19

Donald Hawley once complained that it seemed “extraordinary that so small a place as this can engender so much paper.”20 For him the paper work was the testimony for how “we do so much work” for Dubai’s nascent bureaucracy. This book relies on hundreds of government files that made it into the British National Archives and the British Library. What remains ranges in quality from carefully crafted reports to brusquely sent telegrams. Dossiers from the succession of political agents provide impressions of the political and economic landscape on which modern Dubai was being built. One can begin to piece together strands and fragments of policy decisions across files to suggest the larger picture that might not have ever been fully articulated. The historian Nelida Fuccaro, however, has argued for caution in reading British records. Even after opening their office on Dubai Creek, British officials could not fully grasp the intricacies of inner- and inter-sheikhdom politics, despite the certainty projected in their reporting.21 The British archives offer a particular, and therefore limited, perspective, but they are nevertheless valuable for understanding the motivations behind British policies in Dubai.

Even the British record can seem empty. Instead of clearly stated goals or policies, we are most often left with the minutiae of bureaucratic management. Government papers capture, for example, how one invoice needed an additional report to explain a £3 discrepancy or how an officer’s acquisition of an American, instead of a British, secondhand auto could incur admonishment. On the one hand, minutiae can seem trivial and distracting, both for the historian and the poor bureaucrat too occupied with clerical duties to take in the larger picture. On the other hand, their accumulation can suggest a latent set of guidelines by which the political agency exerted its influence. A consequential policy shift might be delivered in a hasty telegram from London. We can read it closely for its implied messages, perhaps just like the political agent left to explain it to a city of skeptics. These bureaucratic micro-histories make clear that modern urbanization need obey no grand visions, even in a city sometimes referred to at times as a city of spectacle.

Beyond British-government documents, there is also the work of journalists, mostly Westerners, to provide a historical record, but they proved they could be hoodwinked. British advisors in the pay of Dubai’s government and Sheikh Rashid were adept at planting stories and disseminating unsubstantiated statistics. In search of a good story, writers and editors accepted these fictions. Stories became facts. In addition, issues of the London Times and Financial Times in the 1960s and 1970s brazenly overlapped advertising and reporting. There are also various English trade magazines that provided regular coverage of Dubai’s development progress. In many of these articles, it is difficult to differentiate praise for their subscribers’ industries from the praise for Dubai. Some Arabic-language periodicals have also provided additional perspective on the city. One in particular, Akhbar Dubai, published by Dubai Municipality, provides insight into how the local government wanted to convey itself.

There are also the files of John Harris, kept in his home and offices in London. For this book, Harris could only be interviewed once before he died in 2008. He had suffered a number of strokes, which at times left gaps in his memory and at other times allowed a fluid exchange through time and time zones. The interviews that did not happen are among this story’s holes and shadows. In many ways, however, Harris had already done his work. He speaks through buildings, photographs, drawings, and letters. He also left behind lecture notes that offer the menu of anecdotes he arranged according to the occasion.

Focused on the histories of foreign expertise, this book provides minimal elucidation on a significant aspect of Dubai’s urban development, namely the wealthy merchants whose family businesses presided over Dubai’s port since as early as the nineteenth century. Their financial and societal role began to change with the arrival of oil explorers in the 1950s and the local presence of British officers. As they sought new ways to sustain their businesses and maintain their influence on the city, they collaborated with and challenged both Sheikh Rashid and the present British officers.22 Members of these families have been variously described—from profit-motivated traders to would-be political reformists. They were certainly influential local voices, and some of them contributed greatly to Dubai’s urban growth. They built the earliest shopping centers, the sprawling tracts of villas, and the rows of apartment blocks that housed incoming populations.

FIGURE P.7 Sheikh Rashid (center) at construction site, flanked by advisors and experts including John Harris and William Duff (foreground, second and third from left). Courtesy John R. Harris Library.

Though the British government was committed to protecting Maktoum rule, it also realized it shared motives with the merchants. In this way, the merchants shaped British policy in Dubai. More profoundly, their trade connections ensured that the port was filled with the necessary supplies—concrete, steel, air conditioners, automobiles, and building equipment—when a building boom began. These leaders in politics and commerce—counterpoints to the dominating narratives about the Maktoums and British officers—remain frustratingly unresearched. Some of these families are mentioned in this book, but their stories need more attention.

This book tells a story about how experts make a pitch for projects they believe they can manage. Too often today, those contracted to design Dubai treat the city as a ludicrous playground divided up for their own pleasure. “Every architect dreams of being given a blank canvas,” wrote London’s former mayor during his paid publicity stunt for Dubai.23 It turns out, those hired to design for the city surrender restraint more often than they push boundaries. They have condoned sloppiness and shunned intelligence. At the end of a typical design process, presenting architects might step away from their office’s creation, shrug their shoulders, and claim, “But it’s Dubai!” Feigning self-deprecation is cover for shirking professional responsibility. Defense comes in the form of invoices and the hedging of bets to secure the next project. Belittling Dubai while proposing to build it is worse than condemning the city altogether. The joke, the wink, the distancing oneself from one’s own proposal: These are all examples of deliberate obtuseness to conceal professional transgressions.

Unlike much of Dubai’s more recent development proposals (including underwater resorts and Ferris wheel hotels), John Harris’s work was legitimately commissioned, sincerely pursued, and, more often than not, resolutely executed. Nearly all the work Harris’s firm created for Dubai has gone away with time, a testament to its prescribed role in making a city. Although street patterns in “old Dubai” still follow Harris’s designs, their use, density, and build-out hardly abide by Harris’s initial intentions. Reading the cleft between what Harris drew and what Dubai has become provides a great deal of perspective on the city. Dubai might be an authored city, but its contours have yielded to global strategies and economic realignments.

After a brief prelude, this book opens in 1955, four years prior to John Harris’s arrival in Dubai, in the midst of early efforts by the British government to institute a modernization program. The persons involved in these initial British-led efforts were British officers, engineers, an Iraqi consultant, and a would-be monopolist contractor. The success and failures of those experts paved the way for Harris’s arrival in Dubai and his town plan’s influence on the city’s growth. Without them, Harris’s arrival would have had little effect. Once Harris enters the scene in the fourth chapter, the book employs his career in Dubai as a lens through which to observe the city’s early decades of modernization. Presented in a loosely chronological structure, key designs by Harris’s firm reflect Dubai’s economic and political realities. In this way, examples of Harris’s work reveal how such concerns as hygiene, international standards, the gold trade, global migration, and business-class comfort were addressed through designs for hospitals, banks, hotels, and Dubai’s tallest office tower. This book does not cover all of Harris’s work in Dubai, or elsewhere in the world for that matter, but instead focuses on the works that map out Dubai’s early history of constant pitch-making and deal-brokering. It isn’t a coincidence that many of these works were called showpieces.

A city of shiny surfaces. A shallow city. An empty shell. A fake city. These are some accusations casually directed at Dubai today, many of which carry the claim that constructed facades lack authenticity. They suggest that the city is not what it appears and that one needs to locate its “dark side” in order to know the real Dubai.24 Dubai’s urban development has certainly been motivated by appearance. In fact, it was an image problem that likely triggered the British government to formulate the first semblances of a modernization project. Early projects were described as part of a “shop window” campaign. The term “showpiece” might describe shiny structures built for banks and tourists, but in Dubai’s twentieth century the term clarified the purpose of a hospital, a municipal office, and a port—to bear and express evidence of a modern city. Beyond that, a showpiece had reinforced-concrete foundations anchored in the ground. It was evidence that the city was not going to drift away. Secured to the subsurface, the city would keep growing and changing above ground.

Modern architecture made Dubai in the physical sense, but it also delivered an image easily conveyed and broadcasted. Since the summer of 1960, when Harris submitted the town plan, Dubai has enjoyed several booms and survived multiple busts thanks to the delivery of a profit-fueled imaginary. One might say a plan gets you on the map, but constant transformation keeps you there.

1. “Career High Points,” Gulf Business 2, no. 1 (May 1997).

2. Oliver Lindsay, The Battle for Hong Kong 1941–1945: Hostage to Fortune (Stroud, UK: Spellmount, 2007), 157–236.

3. Ibid.

4. The Trucial States was the collective name British-authored documents gave to the sheikhdoms of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah, and Fujairah. The invention of this terminology is further defined in Chapter 1.

5. Donald Hawley, The Emirates: Witness to a Metamorphosis (Norwich, UK: Michael Russell, 2007), 171.

6. Ibid., 29.

7. James Onley, The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 45. Prior to the political agency, an Arab agent paid by the British government, and sometimes a British agent, were stationed in a rented house in Sharjah.

8. Today, Dubai is an emirate and a city of the United Arab Emirates (and before that it was one of the seven sheikhdoms that the British government referred to as the Trucial States; see note 4 above). Since this book is about urbanism, Dubai will be addressed as a city. Its former status as a city-state will be touched upon, as well as its gradual loss of that designation.

9. Minutes of discussions regarding Halcrow’s survey of Dubai and Sharjah Creeks (28 Jan. 1955), National Archives, United Kingdom (NA), FO 371:114696.

10. See, for example, Paul deGive and Thomas A. Roberts, “Rashid—Merchant Prince of the Persian Gulf,” Christian Science Monitor (9 Aug. 1973); and Hawley, The Emirates, 145.

11. See, for example, Graeme H. Wilson, Rashid’s Legacy: The Genesis of the Maktoum Family and the History of Dubai (London: Media Prima, 2006), 25.

12. In Dubai: The City as Corporation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), an important study of contemporary Dubai, Ahmed Kanna analyzes this two-pronged mythology as a living paradox in the chapter titled “The Vanished Village.”

13. Donald Hawley, Desert Wind and Tropic Storm: An Autobiography (Wilby, UK: Michael Russell, 2000), 55.

14. John Darwin, The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 580.

15. Hawley, The Emirates, 19.

16. Adrian Hanna, “Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes Aero Trucial Lodge 9147.” http://www.sixgolds.com/sharjah.htm

17. Kanna, Dubai: The City as Corporation, 174.

18. Address by Robert Gibbons given at the Thanksgiving Service for John R. Harris (12 May 2008), John R. Harris Library.

19. At the time of writing, two of the twenty-three pavilions planned for Dubai’s Al Shindagha Museum have opened, one focused on Dubai Creek and the other on the perfume industry. For several years, foreign consultants have scrambled to find documentation to fill and narrate these museums.

20. Hawley, The Emirates, 223.

21. Nelida Fuccaro, “Review of Ruling Shaikhs and Her Majesty’s Government: 1960–1969 by Miriam Joyce,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 39, no. 3 (August 2007): 480–482.

22. Onley, Arabian Frontier of the British Raj, 1–54.

23. Email (26 June 2008), World Architecture Congress at Cityscape Dubai 2008.

24. See, for example, Johann Hari, “The Dark Side of Dubai,” The Independent (7 April 2009).