“Success breeds complacency. Complacency breeds failure. Only the paranoid survive.”

—attributed to Andrew S. Grove, co-founder and former CEO of Intel1

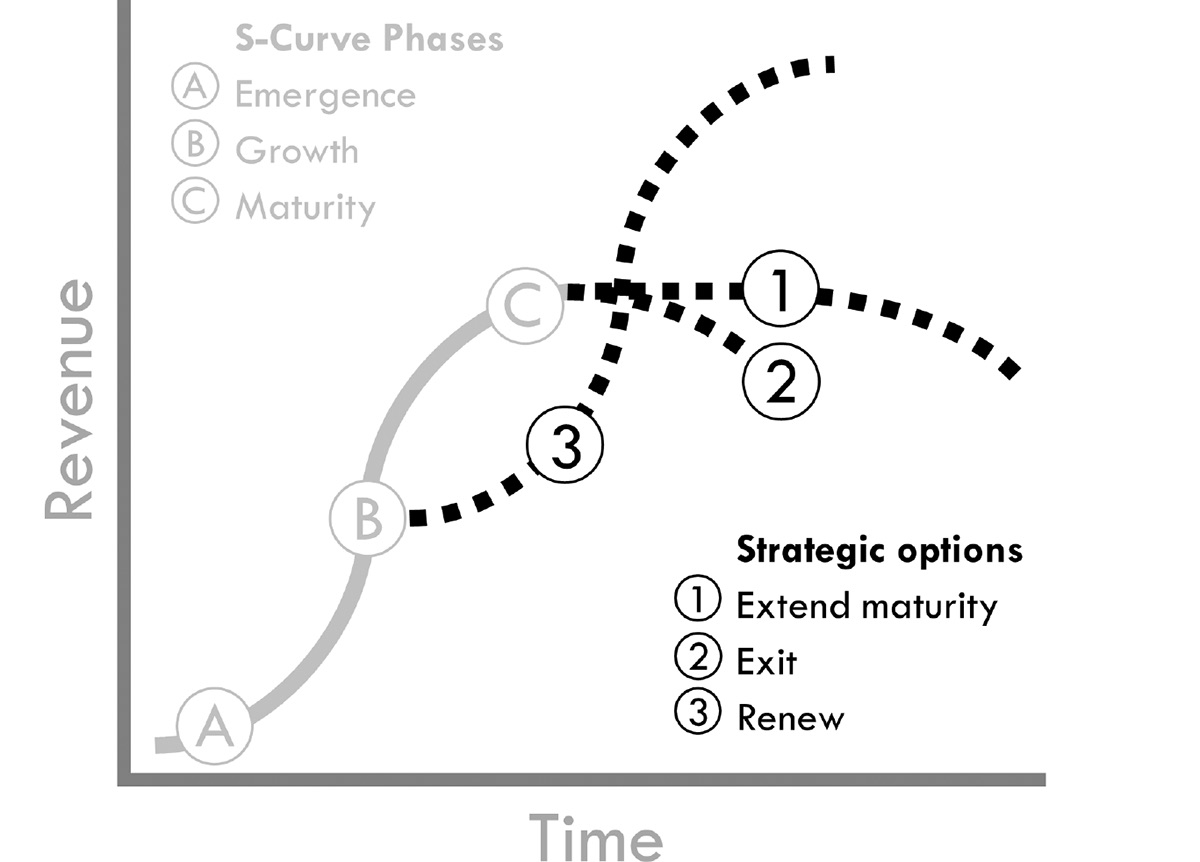

It’s simple. Whether we are talking about a product, process, service, or business model, SMMEs ultimately have three strategic options as they progress toward maturity: extend maturity, exit, or renew (see Figure I.1).

That’s it. Anything else is a variation on these themes.

The most-pursued SMME strategy is to extend maturity, with the weakest companies attempting to do so only by optimizing production while the most capable also invest in incremental product innovation. If you seek only to extend maturity without already exploring opportunities to renew, your competitive position is tenuous at best. Whether at the hand of existing participants in your industry, new entrants, or those bringing entirely new substitute concepts to the market, your days are numbered. Struggling to compete, you will drain the business financially, ultimately facing decline leading to an exit. It is only a matter of when you will either run the company into insolvency or sell it.

Having considered this, are you pleased with your strategy at maturity? Are you pleased with the strength with which you seek to extend maturity? Are you pleased with your attempts, if any, to renew your business? In the quiet of your thoughts, can you truthfully say that you gave all that was appropriately required with an honest and appropriately sustained effort?

If your answer to this last question is “no,” trust that we understand. Strategic success requires a growth mindset. An increasingly aggressive growth mindset is needed the more you move from incremental innovation, characteristic of extending maturity, to the breakthrough innovation characteristic of renewal. There is something different about SMMEs that have attempted and succeeded at innovation. They not only establish a robust capability to extend maturity but, most important, maintain a healthy tension between extending maturity and renewal. While it is easier and cleaner to ignore renewal, ultimately it is deadly. Those that have attempted and succeeded at innovation get it. You see it in the patterns of their behavior.

2016 brought a rare and significant opportunity for Wes-Tech Automation Solutions, an automated production project for an emerging electric vehicle manufacturer that, for the purposes of this book, we’ll call NOVUS.2 The nature of NOVUS’s challenge and how Wes-Tech embraced it illustrate how one SMME attempted and succeeded at renewal.3

The custom automation systems industry, in which Wes-Tech participates, provides various solutions (including assembly and test systems, manufacturing systems, robotic integration, and material-handling conveyors) to multiple industries (ranging from automotive to manufacturing to consumer products to medical to defense).

Competitors within this industry work with two simple business models—providing “made to design” or “made to specification” solutions—or some portfolio combination of the two depending on the mix of customer demand.

With the made-to-design business model, customers know precisely what they want in an automated system and choose to outsource implementation. Here, the customer provides a request for quotation containing the exact design to the supplier; in response, the supplier provides a cost-competitive price quote. This often is the case when the customer is performing maintenance on or updating existing capability. The customer and supplier infrequently interact throughout the engagement, at most to negotiate the project scope and price, preliminary system acceptance, and ultimately final system acceptance. While not without technical contribution by the supplier, such projects are relatively straightforward to deliver.

With the made-to-specification business model, customers know what they want to accomplish but wish to outsource how to achieve the objective. Here, the customer outsources both design and implementation of the custom automation system. This situation often exists when the customer has familiarity with automation systems yet requires the contributions of a supplier with broader expertise gained across time and industries. In these cases, the customer submits a request for proposal framing the problem and providing performance specifications; in response, the supplier provides a price quote and a proposal beginning with an automated system design and ending with implementation. Similar to made-to-design solutions, customer and supplier set specifications early, and infrequently interact throughout the engagement.

The difference between these two business models lies in whether the customer or the supplier designs the automated system. The similarity is that expertise to address the problem is firmly grasped by one or the other.

Finally, to frame Wes-Tech’s story, the custom automation systems industry is characterized by often-unarticulated assumptions and expectations regarding such things as delivery time, problem definition, and the nature of the customer-supplier relationship. While variation exists, new participants in this industry, whether customer or supplier, historically have not questioned these patterns.

In 2016, NOVUS approached vendors in the custom automation systems industry with requirements to mass produce its next-generation, volume production electric vehicle, NOVISSIMA.

The NOVISSIMA represented a challenge unlike anything previously encountered by Wes-Tech and the custom automation systems industry. While many individuals within NOVUS possessed significant manufacturing expertise and experience, the company lacked a collective capability in automated assembly familiar to those established in the automotive industry. Further, NOVUS’s previous experience with fragile body components was limited to hand assembly. How these parts would behave in a high-volume automated assembly line was unknown. Finally, the company defined a time frame for completion that was extremely aggressive by any standard within the custom automation systems industry.

Compounding these issues was that NOVUS had to establish coordination of its production capability across multiple suppliers in the custom automation systems industry. Unlike standard industry practice, a problem experienced by one supplier on the NOVUS NOVISSIMA project might easily have an impact on countless others. Such situations would cause a ripple effect across the production floor, with requirements changing in real time. Ultimately, NOVUS and all its suppliers needed to gain insight into working together, almost as one, to solve the challenges associated with manufacturing this unique project.

These characteristics collectively define an often-confusing environment, one that is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, referred to as VUCA.4 Notably, NOVUS sought to remove “silos” between suppliers, just as it does internally. Further, NOVUS provided estimates and problems that needed to be solved, rather than specific requirements, for many of their needs. A project such as this runs counter to standard practices in the custom automation systems industry in which either customer or supplier possesses design confidence. In contrast, this project’s progress and success were initially stymied more by what NOVUS, Wes-Tech, and other suppliers collectively did not know than by what anyone knew.

Because of this request’s novel and extreme features, it represented a significant diversion and challenge. NOVUS required a new design service paradigm from their suppliers, a new business model that differed from current business models, providing made-to-design or made-to-specification solutions. Only those suppliers who possessed the proven capabilities necessary to overcome these challenges and work within this new business model could meet NOVUS’s needs.

Having no direct experience with a project as novel and extreme as this, and with no time to explore existing processes and paradigms from other industries before embarking on it, the Wes-Tech team responded intuitively, relying on its belief in its existing people and proven capabilities. Wes-Tech’s owners, John Veleris (chairman of JVA Partners5) and George Garifalis (partner at JVA Partners), with Wes-Tech’s president, Jason Arends, saw this as a significant and unique opportunity to lead their industry by collaborating with NOVUS to renew it. Further, they understood that they could accomplish these goals while minimizing risk and cost, as Wes-Tech had a lead customer with which they could work.

The standard industry practice, in which a customer project is delegated to a single project engineer to develop a quote followed by team implementation, had to be abandoned due to ongoing client changes and, within the context of this project, an appropriate lack of direction. Changes to industry standard practice included Wes-Tech forming a small core team of the company’s top technical and business experts meeting daily via conference call with NOVUS and NOVUS’s other suppliers. The Wes-Tech team did so to immerse themselves in understanding NOVUS’s needs, operating culture, and style, and the technical challenges that had to be addressed collaboratively with NOVUS and the other suppliers in real time.

Like NOVUS, Wes-Tech had to return to first principles to move quickly, innovate on the fly, and essentially do the impossible. Wes-Tech leveraged its existing skill in being a customer-centric learning organization to respond to NOVUS’s needs. Yet while all this was necessary, the core team still needed to dedicate itself to the type of 24/7 availability required to meet NOVUS’s aggressive timeline.

While Wes-Tech was building upon its proven capabilities, unplanned (positive) patterns of behavior, process, and business practice emerged. These practices were consistent with those observed in the software industry and in startups, where such projects are more often the norm and upon which NOVUS based its developing company culture.

As the core team members observed, the NOVUS project represented something of a once-in-a-career opportunity to participate in such a unique customer project that could have a significant and lasting impact on the custom automation systems industry. In response, the entire Wes-Tech team, out of necessity, brought their “A game” to this project to develop new ways of operating to deliver on it.

And the outcome?

Wes-Tech’s contribution not only passed acceptance testing but also was explicitly recognized by NOVUS as highly successful. Further, NOVUS posted 2020 robust financial performance reports that bolstered share prices.

Most important for this book, Wes-Tech renewed itself and its industry. It established itself as a new service paradigm provider to a new market—knowledgeable in how to price, specify, and deliver on such projects, accepting and embracing volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity rather than dreading and hiding from them. In early 2022, as we finalize the story shared here, Wes-Tech continues work on other engagements with this and other clients seeking precisely the type of design services described here. And more is on the horizon.

Wes-Tech’s success raises the question as to why it worked for them and what implications are worth noting for SMMEs as a group.

Before engaging with NOVUS, Wes-Tech had successfully designed, implemented, and delivered hundreds of technically innovative custom automated assembly and testing systems in various industries. Each project could be categorized as providing either a made-to-design or made-to-specification solution. Each of these systems was unique, as Wes-Tech designed and built each to meet that customer’s specific assembly component parts and production requirements. This type of work is internally complex, requiring the collaborative involvement of several engineering disciplines such as application design, mechanical, electrical, industrial controls, robotic programming, machine-building trades, and project management to plan and coordinate the complexity of hundreds of interdisciplinary work activities. Further, such work requires broad and deep customer insight.

Even without Wes-Tech’s demonstration of success with NOVUS, they had an enviable track record. Yet in this situation, the Wes-Tech team went above and beyond by working within this new, more engaged business model. What was unique about Wes-Tech’s ability to scope the work and deliver such a highly complex project as NOVUS’s? Why was the company able to manage the diverse project complexity and uncertainty and convert it to a deliverable predictably and consistently?

Answering these questions involves identifying Wes-Tech’s proven capabilities, each of which depends entirely on the company’s people:

• Owners like John and George, leaders like Jason, and numerous employees who understand and embrace the reality that a company must renew to survive and thrive—and, as illustrated in this story, not only accept the reality but run toward it.

• The insight that the cost and risk of renewal can, and should, be managed effectively—in this case, by working with a paying customer.

• Mastery of a suite of perspectives, skills, methodologies, processes, and tools to innovatively address customer needs. For this story, this means the ability to work intimately with both their customer and other suppliers—so intimately that Wes-Tech could assume a more significant leadership role than imagined in standard industry practice by dedicating a cross-functional team to the project 24/7.

• The courage to take on a project of this magnitude, both in size and unique character, and do so in a way that served all.

Admittedly, this story highlights specific capabilities and does not illustrate each of the topics we cover in this book. Yet when considered as a whole, the stories we share present a comprehensive view of what it means to “get it” when it comes to innovation in an SMME.

Wes-Tech’s story is typical of those SMMEs that “get it,” investing in and succeeding at innovation and renewal, in this case by developing the comprehensive set of skills to work within this new-to-industry business model. Yet such companies are few and for various reasons. First, many owners are unwilling to reinvest profits or make an additional investment—in this case, in the diverse, deep set of talent necessary to succeed—as a means of securing future options for growth and renewal. They prefer cash today over long-term viability. Others, often subsequent-generation owners of family businesses, are unfamiliar with, and thus unwilling to take on, what they understand as the risk associated with innovation. They might want to see the company survive and be handed to the next generation but are unsure how to proceed. Still others have made such investments in the past and failed. They see innovation, at best, as a financial roll of the dice.

On one hand, investment in innovation represents an opportunity for SMMEs to renew, to survive and thrive. On the other, innovation is often considered sufficiently difficult, expensive, and risky, so many are unwilling to develop the skills and capabilities necessary to succeed.

The purpose of this book is to help you understand the following:

• The critical importance of innovation investment as well as the weaknesses of typical excuses not to pursue such investment (Chapter 1)

• How design thinking significantly improves the likelihood of successful innovation investment and how SMMEs effectively pursue it (Chapter 2)

• That there is an important, often neglected emotional component in nearly all consumption, an element that can be addressed not only with the product but also the service, packaging, and after-service sensitivity in follow-up (Chapter 3)

• The importance of innovation processes and tools such as phase-gate, lean innovation, open innovation, 2x2 matrices, and roadmaps, as well as how they are effectively deployed in SMMEs (Chapter 4)

• How talented individuals make innovation happen in SMMEs and how best to manage them (Chapter 5)

• The importance of a simple strategic perspective to ensure that you focus innovation on the most impactful opportunities (Chapter 6)

• When you bring all this together, what it looks like when an SMME “gets it” when it comes to innovation that leads to renewal (Chapter 7)

We emphasize six major themes and insights in our book.

1. Renew to survive and thrive: First and foremost, innovation that renews is the lifeblood of any SMME. It is how, as Andy Grove suggested, the paranoid survive and, for that matter, thrive. SMMEs without renewal are on the path to failure. Further, we believe that all—SMME owners, board members, CEOs, presidents or GMs and their leadership teams, innovators, and all other employees—should be prepared, as appropriate for their role, to thoughtfully articulate the case for as well as consider and evaluate innovation investment opportunities.

2. Manageable risk: Second, there are low-risk ways to explore opportunities to renew, from proven methods to hiring the right people. We wish for our readers a growing ability to accept a reasonable amount of uncertainty while expecting serendipity. We want our readers to realize that the real risk is not to innovate: it is to not innovate.

3. Reasonable cost: Third, we address the fallacies held within many SMMEs that innovation is too expensive, too time-consuming, or only for startups or large, mature companies. From design thinking to lean innovation to open innovation to hiring the right people, we share simple, commonsense approaches that are financially responsible and accessible to all. As with risk, innovation is most costly if not undertaken.

4. Proven methods: Fourth, we prepare our readers by concisely exposing them to established perspectives, skills, methodologies, processes, and tools that, when employed collectively, make innovation happen—and do so in a way that is not unnecessarily risky or expensive.

5. Personal courage: Fifth, we want each reader to take with them the understanding that innovation is up to them. All individuals in an SMME should be prepared, and should possess the prudent courage and integrity, to contribute to making innovation happen, as they are best suited for the benefit of all. Such courage may mean that owners, board members, CEOs, and those in executive leadership address the challenges of a culture that has ossified in its inability to embrace innovation. At the same time, those deeper within the organization must not assume that someone else is responsible for renewal.

6. People: Sixth, and finally, successful innovation is about people, several categories of people: SMME owners, board members, CEOs, presidents or GMs and their leadership teams, innovators, and all other employees, and—most important—your customers. This means hiring and effectively managing the right people, those who “get it” when it comes to innovation and act on that understanding. And it means simultaneously focusing on what your customers really need and returning financial rewards to those who invest.

It’s a tall order. But, as we illustrate with multiple examples and stories, it is not beyond your reach. As we discussed while writing this book, “After reading this book, those owning, advising, leading, and working in SMMEs will have no excuse when it comes to innovation.” We are confident that our book can help you and your colleagues survive and thrive in ways not previously imagined.

1. William J. Baumol, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 228.

2. “Your Automation Advantage,” Wes-Tech Automation Solutions, accessed March 1, 2021, https://wes-tech.com/.

3. The Wes-Tech story was developed through a series of private communications with John Veleris, George Garifalis, and Jason Arends between 2016 and 2021. Providing leadership in factory automation since 1976, Wes-Tech designs, builds, and implements innovative automation solutions across a wide variety of industries. For full disclosure, Bruce serves on JVA Partners’ advisory board. JVA Partners owns Wes-Tech.

4. The term VUCA is widely attributed to the United States Army. For additional information about its meaning, see Nathan Bennet and G. James Lemoine, “What VUCA Really Means for You,” Harvard Business Review (January–February 2014): 27–37; and Jeroen Kraaijenbrink, “What Does VUCA Really Mean?” Forbes, December 19, 2018, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ jeroenkraaijenbrink/2018/12/19/what-does-vuca-really-mean/.

5. “Creating Value,” JVA Partners, accessed March 1, 2021, https://jvapartners.com/. Founded in 1998, metro-Chicago-based JVA Partners is an operationally focused private investment firm. For full disclosure, Bruce serves on JVA Partners’s board of directors.