This book is about the growing freshwater challenges facing the United States and the world. It is about how to solve those challenges. It is also about the important role that the private sector can play in solving them and the challenges and problems that will be raised by the private sector increasing its role in water management. Private organizations can contribute to a sustainable and resilient water future, yet private participation in the water sector raises questions about the appropriate roles of government versus the private sector in resolving water issues. Water is a distinctively public resource important to both human health and the environment. Private companies, in turn, have not always found it easy to work in a sector that is both highly public and highly political. To solve the freshwater crisis, the private and public sectors must learn to work together, each contributing its respective expertise and skills to joint solutions.

Freshwater is essential for human health and survival, for the environment, and for virtually every economic activity from growing food to manufacturing microchips. Along with air, freshwater is our most essential resource. Freshwater, however, is also in crisis. The frequency and duration of droughts have increased since 2000, and drought will likely impact three-quarters of the world’s population by the middle of this century. Even without drought, two billion people lack access to safe, accessible, and affordable drinking water. While water quality has improved since 1970, many waterways remain heavily polluted, and water contamination kills two million people every year. As infrastructure ages, leaks are leading to unacceptably large water losses that in some poorer cities approach 65 percent of the water supply. Diversions and dams have seriously altered freshwater ecosystems, threatening a third of freshwater fish species with extinction. Our most essential resource, in short, is at tremendous risk.1

Governments have taken the lead in solving the world’s water challenges for most of the last two hundred years. When concerns arose in the 1800s that poor water quality was causing cholera, typhoid, and other diseases, cities implemented new sanitary measures, often taking over water supply systems from private companies. When rapidly growing cities like New York and Los Angeles outgrew their local water supplies, they built aqueducts and pipelines to import more water. When farmers in the arid western United States demanded irrigation water, the federal government created the Bureau of Reclamation. When heavy rains led to floods, governments around the world rerouted and channelized rivers and erected flood-control dams. Private companies sometimes were involved, but in supporting roles as consultants or contractors.2

As today’s water challenges grow, private organizations—businesses, nonprofits, and philanthropic foundations—are playing an expanding and important role. Technology companies are developing innovative new products and tools to conserve and stretch the world’s water supplies. Social entrepreneurs are helping to provide safe and affordable drinking water as well as sanitation services to the billions of people who lack those basic amenities. Water markets in the western United States, Australia, and elsewhere are providing water users with the flexibility needed to meet water shortages. Impact investment funds are buying water rights to improve the environment while earning financial returns. Private firms are helping to construct and finance needed infrastructure. Private foundations are funding the development of better water information for both water managers and the public. Corporations, through their water stewardship programs, are working to improve water management not only within their businesses but also at a societal level.

The shift toward greater private involvement has been slow, rocky, and largely incomplete. Twenty-five years ago, for example, private water suppliers looked poised to significantly expand their share of urban customers with a promise of better management, but their share has plateaued and the comparative advantages of public and private water suppliers is under active debate. Many cities are even retaking control of, or “municipalizing,” their water systems. The growth in water markets, while real, has also been slower than many economists hoped and expected. Cities in the United States still look first to public coffers, not private equity, to fund water infrastructure. In multiple ways, governments still dominate water management. Yet the increasing involvement of the private sector, while gradual and sometimes halting, is also material and important.

This book examines four primary questions. First, does the private sector promise anything unique in solving the global water crisis? Second, what are the potential risks of growing private involvement? Given the “publicness” of water, private engagement in water is often viewed with suspicion. What are the risks? And how do the risks vary among the different roles that the private sector is playing? Third, what are the challenges that private organizations face in working in a historically public sector? Not only is the water sector dominated by public organizations, but it is also conservative and highly political. Should governments promote greater private involvement and, if so, how? Finally, how can private businesses and governments better partner together to address the freshwater crisis? While the private and public sectors are often seen as competitors, they actually provide complementary competencies.

The rise of the private sector is a global story. To keep the narrative focused and manageable, however, this book looks primarily at the growing role of private organizations in the US water sector. The book occasionally provides examples from other countries, but anyone interested in the role of the private sector outside the United States will want to look more carefully at what is happening in their region of interest. Water is inherently local, and the challenges, institutions, and private involvement vary tremendously from country to country.

Four examples from later chapters illustrate the promise of private involvement: technological innovation, water markets, private infrastructure financing, and universal water data. Start with the importance of technological innovation. Growing water scarcity calls for new sources of water. Few regions are running out of water. Instead, they are running out of inexpensive water, like the water they have historically pulled from surface streams and groundwater. To meet future demand, these regions will need to turn to recycled water, desalination, stormwater capture, and other alternative water sources. Each of these sources, however, will be more expensive than what they have now. Both water reclamation and desalination, for example, require enormous amounts of energy. Innovative technologies promise to lower the costs of these alternative sources while also increasing their reliability and reducing other technical challenges. Existing technology companies and startups are stepping forward to develop and commercialize these technologies (just as private companies have helped revolutionize the energy sector).3

Water markets and the private companies designing and supporting them will also be important. As water scarcity grows, conservation will be increasingly important, particularly in agriculture, which accounts globally for about 70 percent of freshwater withdrawals. Agricultural water use, however, is often unregulated. Regulations, where they do exist, often lag behind what is economically and technically feasible. Water prices are often subsidized, undercutting conservation incentives. Water markets can help to promote greater conservation by providing both an incentive to conserve (since those who save water can sell it) and the financial capital needed for conservation measures.4

Greater access to private capital will also be key. Cities are increasingly falling behind in new infrastructure. Public water suppliers have often failed to charge high enough water rates to replace aging infrastructure and install the new infrastructure needed to keep up with more rigorous drinking-water standards. At the same time, national and state governments have reduced their annual support for local infrastructure needs. Over the next twenty years, about $335 billion will be needed to meet water infrastructure needs in the United States, including transmission, treatment, and distribution. The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided an important infusion of new governmental funding, but it will not come close to meeting the financial gap. Private financing, including public-private partnerships in which private companies design, build, finance, and operate the infrastructure, can help to further reduce the gap, although private financing is still small and unlikely to meet the growing infrastructure need without significant policy changes.5

A final example of how the private sector can help is the provision of better water information. Given water’s importance, the casual observer might think that water managers have ready access to accurate, near real-time data on how much water is available, the quality of that water, where it is needed, and how it is being used. The truth, however, is that governmental managers and regulators often work with incredibly poor information. Sometimes data is not available because it is difficult to collect or because the government does not have the funds to collect it. In other cases, the data is available but not in a usable or easily accessible form. Here again, the private sector is stepping forward. Technology companies are offering new ways to collect needed information, ranging from satellite imaging to AI-enhanced “smart” water meters. At the same time, private foundations are ensuring that water data is universally available to governments, businesses, and civil society.6

This book looks at the expanding role not only of for-profit businesses but also of foundations and nonprofit organizations. All are increasingly involved in water management, and all bring an innovative and sometimes transformative vision to their work. Foundations, which long avoided the water sector out of the belief that nothing could be accomplished, are now investing in efforts to improve the ability of both government and civil society to tackle water challenges. Charitable organizations are playing a vital role in providing safe and affordable drinking water to the world’s poor. Many environmental nonprofits are using market mechanisms, among other tools, to improve and protect the freshwater environment.7

While the private sector is ready to help solve today’s water challenges, the involvement of private organizations in water management raises unique concerns. Virtually every nation in the world recognizes water as a public resource to be managed in the public interest. Even in jurisdictions like the American West that recognize private rights to use water, the water itself belongs to the public. Colorado grants private “appropriative” water rights to farmers and other users, yet its constitution also declares that water is “the property of the public, . . . dedicated to the use of the people of the state.” Other western states explicitly provide that governmental agencies must manage water for the “public interest.”8

The public has a unique interest in the allocation, management, and use of water, a fact that separates water from every other resource. Water allocations can determine which communities thrive and which wither, which businesses grow and which fail, which households enjoy ample water and which must ration. Water management can impact the quality of a community’s drinking water, determining whether the community is lucky enough to enjoy pure water or unlucky enough to receive water laced with contaminants like lead (Flint, Michigan) or nitrates (California’s Central Valley). Water management also determines how well a community is prepared for droughts and long-term climate change and whether the community’s water supplies are sustainable over time. Water management can determine the water quality of a region’s rivers and streams, the health of iconic fish species like salmon and rainbow trout, and the availability of recreational opportunities.

Private water companies were a growth industry in the eighteenth century as newly formed water purveyors sought to meet the needs of emerging cities. But the unique public interest in water—the “publicness of water”—led to growing public ascendency over water in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Worried about private companies’ commitment to universal water access and safe water quality, many municipalities took over water supplies from private purveyors. In the United States, the percentage of private water suppliers fell from 60 percent in 1850 to only 30 percent in 1926. Only governments, moreover, were able and willing to invest the vast sums of money necessary to build the mega-water projects that would import water hundreds of miles to those cities and agricultural regions running short of local supplies.9

In recent years, the rise of two important legal concepts have further highlighted the unique public interest in water: the human right to water and the public trust doctrine. In 2010, the United Nations General Assembly formally recognized “the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights.” (No nation voted against this resolution, although forty-one countries, including the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, abstained.) A growing number of governments also recognize a human right to water under their local laws, including South Africa (by an express provision in its constitution), India (by judicial decision), and California (by statute). However reflected in the law, the human right to water dominates today’s debates over water access, pricing, and quality throughout the world.10

The public trust doctrine emphasizes that the government holds water resources in trust for all members of the public, including future generations, and cannot abdicate its obligation to manage water in the public interest. South African law, for example, states that the government is the “public trustee of the nation’s water resources” and must “ensure that water is protected, used, developed, conserved, managed, and controlled in a sustainable and equitable manner, for the benefit of all persons.” In the United States and other countries, courts have used the public trust doctrine primarily to protect environmental interests in water. In a seminal 1984 case, for example, the California Supreme Court ruled that its state water agency could not permit water diversions that were drying up Mono Lake, the second-largest lake in the state, and must protect environmental interests in the state’s waterways whenever feasible. While fewer countries have formally recognized the public trust doctrine than the human right to water, the doctrine enjoys an outsized role in water debates throughout the world.11

Some observers worry that the increasing role of the private sector threatens the public interest in water. Concern has centered on business involvement that can influence the allocation, use, and pricing of water. Efforts to privatize the delivery of drinking water, for example, have often fueled fears that private companies will raise prices, reduce access to water for the poor, and cut corners on water quality. Driven by such fears, residents and human-rights advocates have protested and derailed privatization efforts in many cities and regions around the world. Critics have similarly condemned companies seeking to promote water markets as “speculators” that would elevate economic returns over equity, fairness, and other public goals. In the words of one anti-privatization manifesto, “Water is a fundamental right and a public trust to be guarded by all levels of government.” As a result, water “should not be commodified, privatized, or traded for commercial purposes.”12

The international community, however, has also recognized that market forces can benefit water management and that, in at least some settings, water is an economic good. In 1992, over 500 experts from 114 countries, 38 nonprofit organizations, and 28 United Nation agencies met in Dublin, Ireland, at the Conference on Water and the Environment, which was organized by the World Meteorological Organization. One of the conference’s major goals was to develop strategies for more effective and sustainable water management around the world. In their final statement, the conferees concluded that water “should be recognized as an economic good.” According to the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development, “Past failure to recognize the economic value of water has led to wasteful and environmentally damaging uses of the resource. . . . Managing water as an economic good is an important way of achieving efficient and equitable use, and of encouraging conservation and protection of water resources.”13

Water, in fact, is neither a pure public good (best allocated by the government) nor a pure private commodity (typically best allocated by markets). Water is best described as a “public commodity,” a resource critical to both public and private needs. Governments have an obligation to protect the human right to water and freshwater ecosystems. But once sufficient water is reserved for these public purposes, water is a commodity that generates economic value to society by enabling the production of food, energy, or other products. Private businesses and markets can help ensure that societies get the maximum economic value from the water available for those activities.14

With proper incentives and regulatory safeguards in place, private businesses can even advance the human right to water, environmental sustainability, and other public goals. Many communities without capital access, for example, have turned to private businesses for the funding needed to expand their water infrastructure and ensure water access to a higher percentage of their populations. Empirical studies have found that privatization of water systems has often led to accelerated capital investment in infrastructure expansion, although investments can also fall short of promises. To promote environmental sustainability, both nonprofit organizations and governments have increasingly turned to water markets to acquire water from farmers and other water users and dedicate that water to increased instream flows.15

Given the public value of water, however, private involvement in the water sector inevitably creates risks, particularly where businesses have direct responsibility for the allocation or delivery of water. The profit incentives of private businesses can subvert public goals where governments do not create proper incentives and regulations, are ineffective at implementing such incentives and regulations, or are subject to corruption. Privatization efforts have sometimes failed dismally even in developed countries. Water markets may work in California or Australia (although controversies have arisen there), but they are unlikely to work well in many regions of the world dominated by weak protections and enforcement systems. The private sector can sometimes bring immense value to water management. The trick is to understand where and under what circumstances it can do so safely.

Companies working in water also must recognize their responsibility to promote and protect human and environmental water rights. While many businesses have historically ignored this responsibility, the importance of the human right to water and the public trust dictates that water companies actively meet this responsibility.16

Private companies wishing to promote better water management often find the water sector a tough slog. For multiple reasons, the public water sector is often not a hospitable environment for new private approaches or ideas. To start with, the public water sector is exceptionally conservative. This is understandable and beneficial to a degree. People want dependable, clean, and safe water and are far less tolerant of risks in the water sector than they might be in other areas. A malfunctioning smartphone is frustrating but tolerable; contaminated water is intolerable.

Other factors, however, have pushed the conservatism beyond what those risks alone would justify. Public water managers typically thrive by managing local politics, not by adopting disruptive new approaches with high but uncertain potential. Successful innovation offers little upside to managers, particularly when the managers are wrestling with short-term budgets and priorities and when the innovation’s payoff is in the future. Failed innovation can attract unnecessary attention and even lead to managers losing their jobs. For these reasons, few public water agencies have anything akin to a research and development program, creative is not a word found in most agency job descriptions, and compensation and bonuses are seldom tied to innovation. Private businesses that seek to introduce new technologies or business concepts to the water sector therefore often meet skepticism or disinterest.17

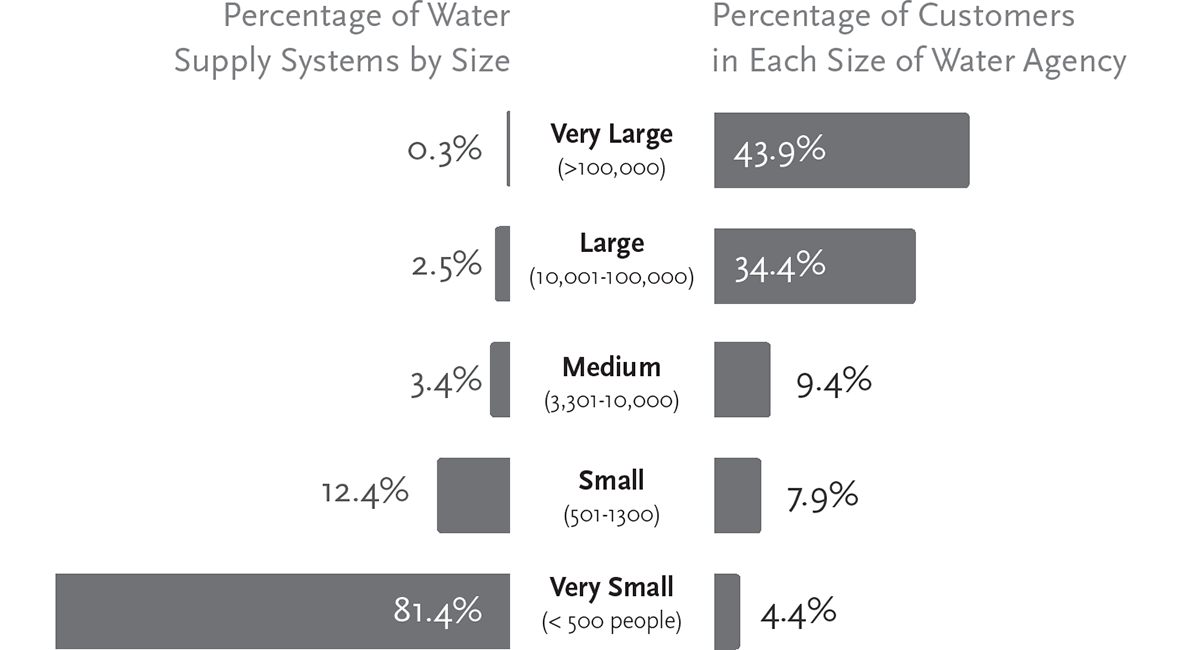

Geographic fragmentation of the water sector also inhibits greater penetration by private firms seeking to introduce new innovations. Ninety percent of Americans receive water from one of approximately 152,000 water supply systems in the United States. (The other 10 percent of Americans have private wells.) There are more water supply systems in America than public elementary, middle, and high schools and postsecondary institutions combined. Two-thirds of water systems are purely seasonal or, like campgrounds, serve changing populations; the remaining third are permanent community water systems with at least twenty-five customers. In some regions, all cities and even some individual subdivisions maintain their own water systems. While 40 percent of Americans receive water from large or very large water systems, over 80 percent of systems serve fewer than five hundred customers. Unlike in private industry, the many inefficient small systems seldom merge with the larger systems.18

This fragmentation can both drive and hinder private involvement in water. With diseconomies of scale and little in-house expertise, small public agencies often must turn to private consultants or service providers for help. Small water agencies, however, often do not have the time, expertise, or scale to identify and adopt recent technologies or new financial options. Private technology and finance companies also face a much more fragmented and diverse market and therefore higher transaction costs in marketing their products and services.19

The publicness of water supply systems also can undermine the economic incentives needed to attract private businesses like technology companies. Public water agencies, which are highly responsive to short-term public pressures to keep prices low, often do not charge consumers the full price of maintaining a sustainable water supply. For similar reasons, they also often underinvest in infrastructure. Rather than charge consumers the full marginal cost of the water they are receiving, public water agencies typically charge a lower average cost and sometimes also subsidize their water deliveries. To keep prices low and the public happy, public water agencies also often do not set aside adequate reserves for replacing and improving needed infrastructure, postponing to a future day (and a future general manager or board) the need to deal with an aging and inadequate system. As a result of low water prices, public agencies often do not have the funding needed to adopt innovative technologies or other private products and services, and customers often do not have an incentive to invest in new conservation technologies.20

For these and other reasons, private businesses often find it difficult to succeed in the water sector. When this happens, the water sector is robbed of the contributions that the private sector can potentially bring to improved water management. Key questions examined in later chapters are whether and how governments can lower the barriers to the private sector without undercutting public interests such as water affordability and how businesses can overcome the barriers that remain.

This book, in summary, is about the growing and important involvement of the private sector in the historically public function of supplying the world’s population with clean, adequate, reliable, and affordable water. It is a story of the unique contributions that the private sector can bring to the global management of water, a resource increasingly threatened by population increases, economic growth, and climate change. But it also is an investigation of how far governments can trust the private sector in the management of the world’s most important natural resource, a resource critical to both human health and the environment, and what oversight is needed. And it is a study of the cultural, political, and institutional clash between an incumbent and historically conservative public sector that views itself as a trustee of the public interest and an emerging and innovate private sector that believes it can improve on the old ways—and make money in the process. Effective partnerships between the public and private sectors will often be the best way forward.

Section I opens the book with an overview of the world’s growing water challenges and the reasons why businesses care about them. Section II examines the two areas in which private involvement has proven most controversial: privatization of municipal water systems and water markets. Critics have worried that both privatization and water markets will lead to an inappropriate commodification of water that threatens the human right to water, the environment, and other public interests. Section III turns to other important but potentially less controversial ways in which the private sector is seeking to improve water management: technological innovation, private financing of infrastructure, expert consulting, and efforts by foundations and nonprofits to promote environmental and equitable goals. Section IV brings the book to a close first by looking at how corporations are addressing the sustainability of their own water use (and, in the process, becoming involved in the public governance of water resources) and then by recommending steps that governments and private organizations should take to promote the beneficial involvement of the private sector in a way that is consonant with the public interest.

1. Stephen R. Carpenter, Emily H. Stanley, and M. Jake Vander Zanden, “State of the World’s Freshwater Ecosystems: Physical, Chemical, and Biological Changes,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36 (2011): 75; UN Convention to Combat Desertification, Drought in Numbers 2022: Restoration for Readiness and Resilience, Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 2022, 4, 18; David Hannah et al., “Illuminating the ‘Invisible Water Crisis’ to Address Global Water Pollution Challenges,” Hydrological Processes 36, no. 3 (2022): 1; World Health Organization, UNICEF, and World Bank, State of the World’s Drinking Water (Geneva: WHO, 2022), 11; World Wildlife Fund, A Deep Dive into Freshwater: Living Planet Report 2020 (Washington, DC: WWF, 2020), 14.

2. Barton H. Thompson, Jr. et al., Legal Control of Water Resources, 6th ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Academic, 2018), 769–777.

3. Newsha K. Ajami, Barton H. Thompson, and David G. Victor, The Path to Water Innovation (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2014); Xavier Leflaive, Ben Krieble, and Harry Smythe, “Trends in Water-Related Technological Innovation: Insights from Patent Data,” OECD Environment Working Paper No. 161, OECD Publishing, Paris, France, April 2020.

4. Howard Chong and David Sunding, “Water Markets and Trading,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 31 (2006): 244–246; Janet C. Neuman, “Beneficial Use, Waste, and Forfeiture: The Inefficient Search for Efficiency in Western Water Use,” Environmental Law 28, no. 4 (1998): 923–962; Thompson, Legal Control, 306–307.

5. Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Public Law 117–58 (2021); N. Grigg, “Aging Water Infrastructure in the United States,” in Resilient Water Services and Systems: The Foundation of Well-Being, ed. Petri Juuti et al. (London: IWA Publishing, 2019), 31–46; Bastien Simeon, “The Financing Gap: Re-examining the Role of Private Financing and P3s,” Water Finance and Management, October 26, 2021.

6. Andrea Cominola, Ian Monks, and Rodney A. Stewart, “Smart Water Metering and AI for Utility Operations and Customer Engagement: Disruption or Incremental Innovation?” HydroLink 4 (2020): 114–119; Nathan Huttner, Kathy Francis, and John Whitney, Sustainable Governance and Funding for Open Water Data in California, Redstone, May 2018; Aspen Institute, Internet of Water: Sharing and Integrating Water Data for Sustainability, Washington, D.C., 2017; Forrest S. Melton et al., “OpenET: Filling a Critical Data Gap in Water Management for the Western United States,” JAWRA: Journal of the American Water Resources Association 58, no. 6 (December 2021): 971–994 (originally published November 2, 2021).

7. Eloise Kendy et al., “Water Transactions for Streamflow Restoration, Water Supply Reliability, and Rural Economic Vitality in the Western United States,” JAWRA: Journal of the American Water Resources Association 54, no. 2 (2018): 487–504; Shyama V. Ramani, Shuan SadreGhazi, and Suraksha Gupta, “Catalysing Innovation for Social Impact: The Role of Social Enterprises in the Indian Sanitation Sector,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 121 (2017): 216–227; Water Funders Initiative and Water Table, “Overview,” March 2021.

8. See Colo. Const., Art. XVI, § 5; Mark Squillace, “Restoring the Public Interest in Western Water Law,” Utah Law Review 2020, no. 3 (2020): 627.

9. Patrick Trent Greiner, “Community Water System Privatization and the Water Access Crisis,” Sociology Compass 14, no. 5 (2020); Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

10. The Human Right to Water and Sanitation, G.A. Res. 64/292, § 1, U.N. Doc. A/RES.64/292 (July 28, 2010); S. Afr. Const. § 27(1)–(2), 1996; Narmada Bachao Andolan v. Union of India, 10 S.C.C. 644 (2000); Cal. A.B. 685 (2012); Mike Muller, “Free Basic Water—A Sustainable Instrument for a Sustainable Future in South Africa,” Environment and Urbanization 20, no. 1 (2008): 67; Barton H. Thompson, Jr., “Water as a Public Commodity,” Marquette Law Review 95 (2011): 17.

11. National Water Act 36 of 1998 § 3(1) (S. Afr.); National Audubon Society v. Superior Court, 658 P.2d 709 (1983); David A. Callies and Katie L. Smith, “The Public Trust Doctrine: A United States and Comparative Analysis,” Journal of International and Comparative Law 7 (2020): 41; Philippe Cullet, “Water Law in a Globalised World: The Need for a New Conceptual Framework,” Journal of Environmental Law 23, no. 2 (2011): 233; Thompson, “Water as a Public Commodity.”

12. “The Cochabamba Declaration, December 8, 2000,” in ¡Cochabamba! Water War in Bolivia, ed. Oscar Olivera (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004); Maude Barlow, Blue Covenant: The Global Water Crisis and the Coming Battle for the Right to Water (New York: New Press, 2007); Vandana Shiva, Water Wars: Privatization, Pollution, and Profit (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2002).

13. International Conference on Water and the Environment, The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development, Dublin, Ireland, 1992.

14. Thompson, “Water as a Public Commodity.”

15. Jennifer Davis, “Private-Sector Participation in the Water and Sanitation Sector,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30 (2005): 145; Thompson, “Water as a Public Commodity.”

16. United Nations, “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect, and Remedy’ Framework,” 2011; Noura Barakat, “The UN Guiding Principles: Beyond Soft Law,” Hastings Business Law Journal 12, no. 3 (2016): 591; Jernej Letnar Cernic, “Corporate Obligations Under the Human Right to Water,” Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 39, no. 2 (2011): 303; John Ruggie, “The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, Cambridge, Massachusetts, May 15, 2010.

17. Ajami, Thompson, and Victor, Path to Water Innovation; Michael Kiparsky et al., “The Innovation Deficit in Urban Water: The Need for an Integrated Perspective on Institutions, Organizations, and Technology,” Environmental Engineering Science 30, no. 8 (2013): 395; Geoff Mulgan and David Albury, “Innovation in the Public Sector,” Strategy Unit, United Kingdom Cabinet Office, London, 2003; Barton H. Thompson, Jr., “Institutional Perspectives on Water Policy and Markets,” California Law Review 81, no. 3 (1993): 671.

18. Ajami, Thompson, and Victor, Path to Water Innovation; Melissa S. Kearney et al., In Times of Drought: Nine Economic Facts about Water in the United States (Washington, DC: Brookings Institute, 2014).

19. Ajami, Thompson, and Victor, Path to Water Innovation; Kearney et al., In Times of Drought.

20. John C. Morris, “Planning for Water Infrastructure: Challenges and Opportunities,” Public Works Management and Policy 22, no. 1 (2016): 24; Ajami, Thompson, and Victor, Path to Water Innovation.